How has U.S. tax policy contributed to inequality in the past few decades? What would be the impacts of the different tax policies the Democratic presidential candidates are proposing? What can be done to prevent corporations from avoiding paying taxes? We interviewed Gabriel Zucman, Associate Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley and co-author (with Professor of Emmanuel Saez) of the book Triumph of injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay, which David Leonhardt of the New York Times called “the most important book on government policy that I’ve read in a long time.”

What is the general argument of Triumph of Injustice?

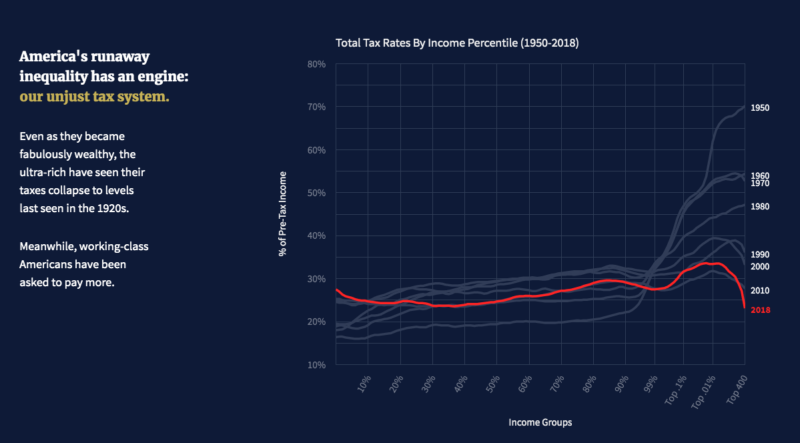

In the book, we construct new theories showing how much each social group has paid in taxes as a fraction of their income all the way back to 1913 and up to 2018, which is the year following President Trump’s tax reform. And what we find is that, in 2018, for the first time ever, the super-rich billionaires paid a lower tax rate than everybody else.

In the book, we construct new theories showing how much each social group has paid in taxes as a fraction of their income all the way back to 1913 and up to 2018, which is the year following President Trump’s tax reform. And what we find is that, in 2018, for the first time ever, the super-rich billionaires paid a lower tax rate than everybody else.

If you look at the U.S. today, the average tax rate is 28%. Each group of the population—the working class, the middle class, the upper middle class, the rich—pays around 28% of their income in taxes. So the U.S. tax system looks like a big flat tax, where the tax rate doesn’t increase with income, except for the ultra wealthy, who pay only 23%. That’s taking into account all taxes paid at all levels of government—so not only individual income tax, but also corporate income tax, consumption taxes, estate taxes, and so on.

What’s very important to realize is that 2018 is the first time this happens, that the U.S. tax system is so regressive and so unfair. If you look, for instance, at the 1950s, the very rich paid 70% of their income in taxes. This effective tax rate gradually declined and, following the Trump tax reform that became effective in 2018, it reached its historical minimum, this effective tax rate of the very rich of 23%.

That’s what we call the “triumph of injustice.” The book tells the story of how the U.S. moved from having the most progressive tax system in the world—with a tax system where the super rich pay much higher tax rates than the working class and the middle class—to a tax system that’s regressive and is now an engine of inequality. Because of course, if they only paid 23% of their income in taxes, it becomes very easy for the super wealthy to accumulate more and more wealth, without any barrier. And with wealth comes power, including the power to influence policy for their own benefit, like influencing tax policy, getting extra tax cuts, and so on. That’s the current situation.

What do you propose can be done about this?

The other dimension of the book, which is probably even more important beyond establishing these facts, is to offer solutions. How could tax justice prevail? How could tax progressivity be restored? How can we have a fair tax system in the 21st century? We describe a number of solutions.

Many people have become convinced that it’s impossible to tax the rich in today’s economy because of globalization: corporations will move abroad, the rich will move abroad, or because of modern technology, there will be tax avoidance opportunities, or the rich will hide assets. There is this view that nothing can be done—and this view is wrong.

What we explain in the book is how it’s possible to have a highly progressive tax system today through a combination of various taxes. The most important one is probably a progressive tax on net wealth, taxing wealth itself—all assets real and financial, net of debts. Along the line of what Elizabeth Warren has proposed and what Bernie Sanders is proposing. In the case of Elizabeth Warren, she proposes to tax wealth above $50 million. So if you have less than $50 million, you pay zero, and then on the first dollar above $50 million, you pay two cents. Bernie Sanders has a similar plan that starts at $32 million, but with tax rates that go up to 8% for wealth above $10 billion. A progressive wealth tax like that would be a very powerful way to restore tax progressivity and to curb the rise of wealth concentration.

But we also describe other solutions. The wealth tax would not solve every problem. You also need to fix the income tax. You also need to make sure that big corporations pay taxes. And so we have solutions for that. That’s what the book does. The situation today is sad and dramatic in many ways, but the message from the book is a message of hope. It’s possible in today’s economy to make the rich pay their fair share.

What are some of the impacts of the current tax structure?

When you have a tax system that’s a giant flat tax, where everybody pays roughly the same tax rate of 28%, except the very rich who pay only 23%, you have two problems. One problem is that high tax rates of close to 30% for the working class and for the middle class make it difficult for these parts of the population to accumulate wealth, to save and to build wealth. The reason why they face high tax rates is because payroll taxes are high and have increased since the 1950s. Sales taxes and consumption taxes in general are high and burden the working class heavily. So you have high tax rates that make it harder for the working class to save and accumulate wealth.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, when the super rich have a tax rate of only 23%, and they earn hundreds of millions of dollars in income each year, that means their wealth mechanically accumulates without any barrier. And so you have a snowballing effect where the rich get richer by virtue of being already rich.

For a long time, the tax system prevented this from happening by limiting the snowballing wealth accumulation effect. When you have 70% tax rate on the rich, it makes it harder for the rich to become richer mechanically. But with a 23% tax rate, there’s no barrier anymore, and so inequality increases.

It has increased dramatically already. If you look at the share of wealth owned by the top 0.1% richest Americans, in 1982 it was 7%. Today it’s about 20%. So this share has been multiplied by three. Twenty percent of wealth—the share of wealth owned by the top 1% richest Americans—is about as large as the share of wealth owned by the bottom 90% of American families.

You have the top 1% richest families who own as much wealth as the bottom 90%. You have the wealth of the top 0.1% that keeps rising and rising faster than average wealth, with a dysfunctional, unfair tax system such as the one we have today, the rise of inequality will continue. With a fairer tax system, with a more progressive tax system, the rise of inequality can be stopped and we can even start thinking about the decline in wealth concentration.

Talk about the website you’ve developed as part of this project.

The book comes with a website, which is really essential for the project as a whole. The website is taxjusticenow.org, and there’s a website that allows people, no matter their knowledge about economics or their party or political stripe, to simulate tax reforms in a simple and user-friendly way.

The website starts from the current progressivity of the tax system, how much taxes as a percent of income each group pays. The user can create new taxes or change parameters of the current tax system. So, for instance, what would happen if the top marginal income tax rate was increased to 70%, which is what Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed a few months ago? How much tax revenue would this generate? Or what would happen if the U.S. created a wealth tax like the wealth tax proposed by Elizabeth Warren? How would that increase the tax progressivity? How much tax revenue would this generate? How would this affect the dynamic of inequality?

The website starts from the current progressivity of the tax system, how much taxes as a percent of income each group pays. The user can create new taxes or change parameters of the current tax system. So, for instance, what would happen if the top marginal income tax rate was increased to 70%, which is what Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed a few months ago? How much tax revenue would this generate? Or what would happen if the U.S. created a wealth tax like the wealth tax proposed by Elizabeth Warren? How would that increase the tax progressivity? How much tax revenue would this generate? How would this affect the dynamic of inequality?

The website is a tool for the public to participate and make the tax debate democratic again. Taxation is an extremely important policy in any democracy. Through the tax system, Americans share a third of their income. In other countries, it’s even more than that, it’s 40% or 50%. Half of their income is shared through the tax system. So making sure that tax system is fair, that it works well, is a central democratic question.

Our view is that it is not for economists to decide on taxation, to say, that’s the best way to proceed, that’s the optimal tax rate. No, it’s for the public with facts, with good information about who pays what and how different taxes could change these effective tax rates.

What do you hope people take away from the book and website?

There is no fixing inequality without fixing the tax system. And so if you care about the future of inequality, if you care about the future of globalization and the future of democracy, you need to read this book. Because if the policies that are implemented keep rewarding the super rich at the expense of everybody else, and keep rewarding the big winners from globalization, the big multinational companies and their shareholders, at the expense of those who don’t benefit much or suffer from globalization, then you can see that globalization is in trouble and even democracy is in trouble.

To have sustainable globalization, you need to make sure that the winners from globalization pay more taxes, instead of paying less. And that’s what we try to do in the book and with the website. We explain that this is possible.

Populism—a political ideology that vilifies economic and political elites and instead lionizes ‘the people’—has spread like wildfire throughout the world. In his recent book,

Populism—a political ideology that vilifies economic and political elites and instead lionizes ‘the people’—has spread like wildfire throughout the world. In his recent book,

In 2017, Rodenbiker published “

In 2017, Rodenbiker published “ Rodenbiker discovered that, while ecological zoning projects are often executed at the municipal level, the dictates for their creation come from all levels of Chinese government and society. He notes that the work of ecological scientists from the 1980s, along with the work of ecological Marxists and economists from the 1990s and 2000s, coalesced to “articulate this green development platform that now goes under the name of ecological civilization-building.”

Rodenbiker discovered that, while ecological zoning projects are often executed at the municipal level, the dictates for their creation come from all levels of Chinese government and society. He notes that the work of ecological scientists from the 1980s, along with the work of ecological Marxists and economists from the 1990s and 2000s, coalesced to “articulate this green development platform that now goes under the name of ecological civilization-building.”

Among undergraduates, economics is sometimes regarded with suspicion (or good-natured ribbing) as a major for students hoping for lucrative post-graduation jobs at big banks and trading companies. Olney is quick to challenge that stereotype. “Probably the least important thing we do is create people who can become gurus at Goldman Sachs,” she says. “The most important thing we do is equip people with skills that allow them to be policymakers, to make a big difference in the world, through using their economic skills.”

Among undergraduates, economics is sometimes regarded with suspicion (or good-natured ribbing) as a major for students hoping for lucrative post-graduation jobs at big banks and trading companies. Olney is quick to challenge that stereotype. “Probably the least important thing we do is create people who can become gurus at Goldman Sachs,” she says. “The most important thing we do is equip people with skills that allow them to be policymakers, to make a big difference in the world, through using their economic skills.”

In an interview, Auerbach, who is Robert D. Burch Professor of Economics and Law at UC Berkeley and Director of the

In an interview, Auerbach, who is Robert D. Burch Professor of Economics and Law at UC Berkeley and Director of the

What does it take for a nation to maintain peace in the aftermath of a civil conflict involving rebel groups or militants? And what role can the international community play in supporting this peace? Aila Matanock, Assistant Professor in the UC Berkeley Department of Political Science, tackles these questions (among others) in her recently released book,

What does it take for a nation to maintain peace in the aftermath of a civil conflict involving rebel groups or militants? And what role can the international community play in supporting this peace? Aila Matanock, Assistant Professor in the UC Berkeley Department of Political Science, tackles these questions (among others) in her recently released book,  As an example, she points to the 1994 election in El Salvador, when the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) first participated as a political party. She notes that the government, claiming security concerns, tried to move polling stations from FMLN strongholds into a departmental capital, making it difficult for FMLN supporters to vote. “That’s reducing the power of FMLN in the election,” Matanock explained. “That’s the kind of maneuvering that can lead to a flare-up of violence, but in this case, international election observers were able to see this violation by the government and say, we’re not buying that these are legitimate security concerns. There are going to be consequences if you don’t move these polling stations back, and we can provide logistics and security if you do.”

As an example, she points to the 1994 election in El Salvador, when the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) first participated as a political party. She notes that the government, claiming security concerns, tried to move polling stations from FMLN strongholds into a departmental capital, making it difficult for FMLN supporters to vote. “That’s reducing the power of FMLN in the election,” Matanock explained. “That’s the kind of maneuvering that can lead to a flare-up of violence, but in this case, international election observers were able to see this violation by the government and say, we’re not buying that these are legitimate security concerns. There are going to be consequences if you don’t move these polling stations back, and we can provide logistics and security if you do.”

From the start of her academic career, Dr. Charis Thompson, Chancellor’s Professor and Chair of the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, has been deeply interested in using the qualitative social sciences to explore the role of science in society. As an undergraduate at Oxford University, she was the first woman member of the

From the start of her academic career, Dr. Charis Thompson, Chancellor’s Professor and Chair of the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, has been deeply interested in using the qualitative social sciences to explore the role of science in society. As an undergraduate at Oxford University, she was the first woman member of the

“Bikes are great…but they’re not infallible,” says

“Bikes are great…but they’re not infallible,” says  There are other narratives for what a typical bicyclist looks like, Stehlin notes, pointing to the example of the

There are other narratives for what a typical bicyclist looks like, Stehlin notes, pointing to the example of the

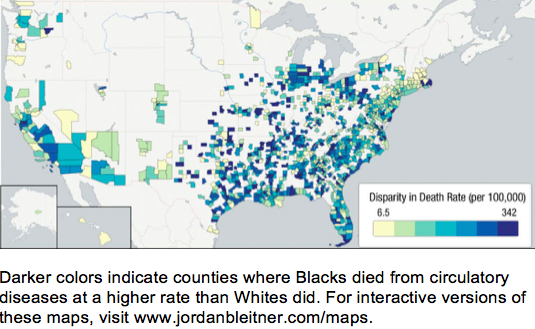

Leitner: A couple factors. One is that [the link between] racial disparity and cardiovascular health has been really pronounced and pervasive for many years, in that blacks tend to show poorer cardiovascular health compared to whites. So we wanted to understand whether one contributing factor to that disparity might be racial hostility from whites. It’s stressful to engage in interpersonal interactions with people who are biased against your group, and that stress over time has negative effects on cardiovascular health.

Leitner: A couple factors. One is that [the link between] racial disparity and cardiovascular health has been really pronounced and pervasive for many years, in that blacks tend to show poorer cardiovascular health compared to whites. So we wanted to understand whether one contributing factor to that disparity might be racial hostility from whites. It’s stressful to engage in interpersonal interactions with people who are biased against your group, and that stress over time has negative effects on cardiovascular health. Matrix: Much of your work revolves around healthcare and uses data from public health organizations. Do you think that we need to see racism as a public health issue?

Matrix: Much of your work revolves around healthcare and uses data from public health organizations. Do you think that we need to see racism as a public health issue?

Meanwhile, Meché describes how her gender has affected her experience conducting fieldwork in Sahel, a vast region south of the Sahara. Her research—focused on peacekeeping, disaster response, and military technologies—requires traversing the heavily male-dominated spaces of security studies and counterterrorism.

Meanwhile, Meché describes how her gender has affected her experience conducting fieldwork in Sahel, a vast region south of the Sahara. Her research—focused on peacekeeping, disaster response, and military technologies—requires traversing the heavily male-dominated spaces of security studies and counterterrorism.