On November 29th, Social Science Matrix will host a panel sponsored by the Center for Right Wing Studies entitled, “Reflections on the 2016 Election and the Republican Party Under President Trump.” Participants include Dr. Lawrence Rosenthal, Founding Director, Chair, and Lead Researcher of the Center for Right Wing Studies; Professor Carole Joffe from UCSF’s Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health; and Professor Paul Pierson, from UC Berkeley’s Department of Political Science. The Center for Right Wing Studies supports research that examines the diversity of right-wing movements and brings together scholars and students to discuss right-wing ideology and politics. Below is an interview with Dr. Rosenthal. [This interview has been edited for content.]

On November 29th, Social Science Matrix will host a panel sponsored by the Center for Right Wing Studies entitled, “Reflections on the 2016 Election and the Republican Party Under President Trump.” Participants include Dr. Lawrence Rosenthal, Founding Director, Chair, and Lead Researcher of the Center for Right Wing Studies; Professor Carole Joffe from UCSF’s Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health; and Professor Paul Pierson, from UC Berkeley’s Department of Political Science. The Center for Right Wing Studies supports research that examines the diversity of right-wing movements and brings together scholars and students to discuss right-wing ideology and politics. Below is an interview with Dr. Rosenthal. [This interview has been edited for content.]

Matrix: What are your initial takeaways from the election?

Lawrence Rosenthal: Donald Trump succeeded in galvanizing the populist Right, which in large measure had been part of the Tea Party, where there was existing resentment for the Republican establishment. That resentment had coalesced around the issue of immigration, and what Trump did by coming out so heavily and so outrageously on the question of immigration—both Mexican and anti-Muslim immigration—is galvanize that support in a way that had never been seen before. As his message spread, he brought in new groups beyond the existing populist right—members of the white working class, particularly men; people who made the transit from voting Democrat to voting Republican; and people who had stopped voting. He mobilized voters who had been indifferent and who hadn’t participated. And finally, he mobilized the American fringe. He mobilized the white nationalist/militia right, who could not believe that the kinds of things they had been thinking about for years and could not get beyond the fringes of American politics were suddenly viable at the level of presidential politics. So in a funny way, what Trump did was take the existing Republican populism and expand it with these other categories, but what he also did successfully was make Hillary Clinton toxic. The push that allowed him to go over the top was bringing on in August a new campaign management from the alt right—in particular, people who had specialized in, how do we say, conspiracy theories on Hillary Clinton for many years.

Matrix: What does Trump’s win say about the state of the American Right?

Rosenthal: It’s totally transformed. Trump split the Republican Party down the middle between traditional conservatives and populists, and there are many variations in both of those categories, but he split them down the middle and found that traditional conservatives—meaning, post-Ronald Reagan-era conservatives—rejected Trump because he did not stand for the ideological fundamentals the Republican Party had stood for for many years. And he also split the Tea Party along the same lines. The Tea Party finally had a terrific debate within it about Trump vs. Cruz, and when Trump essentially clinched the nomination, the heart went out of the Tea Party, and it’s no longer anything like it has been for the past eight years. It is an entirely restructured Republican Party under the leadership of Donald Trump, and what it most resembles right now is not about free trade or free market, but the kind of anti-immigrant, extreme right parties that have been around the fringes of European democracies for many years, parties like the National Front in France and others of that nature. He’s transformed the party and leaped over the successes of these parties in Europe to win the national election, which none of these parties has ever done.

Matrix: Now that he’s won, what will the next four years look like in this country?

Rosenthal: That’s a question of such magnitude that no one knows where to begin. In my view, a lot of focus is going to be on how the Trump government deals with protests. I think there will be a lot to pay attention to, like immigration policy, taxation policy, voting rights policy, the Supreme Court, and so forth. But what people aren’t yet talking about—and which I think will become fundamental in whatever the dramas of the next four years are—will focus on how they deal with protests, and what kinds of opposition they tolerate and how they deal with opposition they don’t tolerate.

Matrix: What are the implications for the Democrats?

Rosenthal: Can the Democrats put themselves together a coherent party? Can they find a way to integrate the movements from the left, the left-wing populism, to oppose Donald Trump’s right-wing populism? Is there some way of integrating that energy into the party? At the same time, the party faces great problems in terms of what’s going to happen by way of voter rights, with the Republican Party being in charge of all branches of government. The restrictions we’ve seen on initiatives to suppress the vote through voting rights laws—the capacity to oppose those efforts—is going to be diminished. And so the Democrats not only have the problem of putting together a coherent party and taking note of the energy on its left, but it also has the problem of its constituency being marginalized in terms of voting power.

Matrix: What would you say were the most important factors that led to the major Republican surge across the country?

Rosenthal: There’s the long term and the short term. The long term is about the immiseration of the American middle class. Up until this election—for example, in the 2012 election, Barack Obama turned his message into a campaign to try to make life better for the American middle class. One of the changes from this election is that the class rhetoric has turned toward the working class. But if you’re talking about working class or middle class, there has been a slow deterioration in the life chances of the middle class and the working class since, I would say, 1973. So it was like a slow-moving wave, and that wave to some extent broke during the financial crisis of 2008, which created the Tea Party. Throughout the Obama years, the people who believed that Tea Party activism was going to fix this became increasingly disenchanted with the Republican Party. And as I mentioned, the disenchantment fused around one issue, immigration. And once Donald trump electrified the anti-immigration vote, he managed to bring a momentum. It’s sort of like reaping a whirlwind that had been building since the ‘70s, became extreme with the financial crisis, and then, during the Obama years, managed to turn people on the right against the Republican Party. Trump managed to grasp that whirlwind.

Matrix: What do you hope comes out of the panel discussion at Matrix?

Rosenthal: I hope that serious academic and scholarly analysis will be brought to bear what happened and what’s likely to happen. And to some extent, I hope it will air whether the changes to come are just cause for fear.

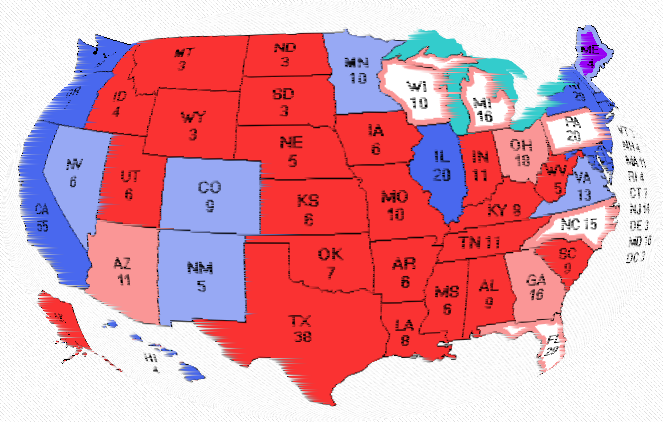

Image: http://www.electoral-vote.com/

“The best analogy to human language that one can find is birdsong,” says Madza Farias-Virgens, a doctoral student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Anthropology, citing a comparison that researchers have been making since the publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

“The best analogy to human language that one can find is birdsong,” says Madza Farias-Virgens, a doctoral student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Anthropology, citing a comparison that researchers have been making since the publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

“The buildings have been pretty much dismissed by history,” says

“The buildings have been pretty much dismissed by history,” says  In short order, the buildings’ architects came under attack by Stalin-era elites in search of scapegoats for Stalin’s (and their own) misdeeds. Khrushchev, himself a major beneficiary of Stalin’s patronage, joined the chorus of critics at a builder’s conference held in Moscow in December 1954. “Right as they were being realized, these buildings became villains on the Moscow cityscape,” Zubovich notes. The new regime tried to counteract the influence of these steely giants through large-scale,

In short order, the buildings’ architects came under attack by Stalin-era elites in search of scapegoats for Stalin’s (and their own) misdeeds. Khrushchev, himself a major beneficiary of Stalin’s patronage, joined the chorus of critics at a builder’s conference held in Moscow in December 1954. “Right as they were being realized, these buildings became villains on the Moscow cityscape,” Zubovich notes. The new regime tried to counteract the influence of these steely giants through large-scale,  Harnessing the skyscraper—once the quintessential symbol of unruly, urban capitalism—and exporting it to capital cities like

Harnessing the skyscraper—once the quintessential symbol of unruly, urban capitalism—and exporting it to capital cities like

To uncover why someone might find something as seemingly innocuous as low-frequency vocal pitch irritating, we spoke with

To uncover why someone might find something as seemingly innocuous as low-frequency vocal pitch irritating, we spoke with

The interviews, collectively titled “Urbanismo Participativo/ Participatory Urbanisms,” are displayed online in a carefully designed diptych, a conceptual form used in visual art to extend canvases and draw parallels. Readers also have the option of downloading the interviews as a

The interviews, collectively titled “Urbanismo Participativo/ Participatory Urbanisms,” are displayed online in a carefully designed diptych, a conceptual form used in visual art to extend canvases and draw parallels. Readers also have the option of downloading the interviews as a  This ambitious project statement is fulfilled by the scope and scale of the work itself. The interviewers, including both Larson and Shankar as well as a number of research assistants, elicit provocative, deeply thoughtful reflections on the intersections of time and space, the performance of collectivity, the fact of urban multiplicity, pedagogical practice, voice, mediation, and the relationship between individual city dwellers and city infrastructures. Interviewees reflect on challenging issues of urban informality and inequality—on the fact that, in the words of Ravi Vasudevan of the SARAI Collective, people live in these cities “despite not being allowed to have all sorts of things that they should be allowed to have.”

This ambitious project statement is fulfilled by the scope and scale of the work itself. The interviewers, including both Larson and Shankar as well as a number of research assistants, elicit provocative, deeply thoughtful reflections on the intersections of time and space, the performance of collectivity, the fact of urban multiplicity, pedagogical practice, voice, mediation, and the relationship between individual city dwellers and city infrastructures. Interviewees reflect on challenging issues of urban informality and inequality—on the fact that, in the words of Ravi Vasudevan of the SARAI Collective, people live in these cities “despite not being allowed to have all sorts of things that they should be allowed to have.” Shankar recalls being particularly moved by two of the articles in the “Austerity Politics, Performance, and Occupation” section, which emerged from participant ethnographic research in Athens and Madrids. She and Larson describe these essays thus: “[They] present urgent and vivid ethnographic accounts of the urban manifestations of radical democratic responses to Europe’s contemporary austerity regimes. Andreea Micu’s reading of the affective forms of protest around ongoing housing struggles in Rome and Madrid identifies ‘indignation’ as the prevailing affect in times of austerity…. Her article] explores how this affect is mobilized to powerful effect in street protests…. [Gigi Argyropoulou’s article] describes how emergent and collective participatory practices in the occupied [Embros theatre in Athens during the debt crisis] may have faced repeated failures, but succeeded in marking a paradigm shift, thereby opening up the space of possibles for alternate ‘instituent’ practices of politics and culture in times of austerity.”

Shankar recalls being particularly moved by two of the articles in the “Austerity Politics, Performance, and Occupation” section, which emerged from participant ethnographic research in Athens and Madrids. She and Larson describe these essays thus: “[They] present urgent and vivid ethnographic accounts of the urban manifestations of radical democratic responses to Europe’s contemporary austerity regimes. Andreea Micu’s reading of the affective forms of protest around ongoing housing struggles in Rome and Madrid identifies ‘indignation’ as the prevailing affect in times of austerity…. Her article] explores how this affect is mobilized to powerful effect in street protests…. [Gigi Argyropoulou’s article] describes how emergent and collective participatory practices in the occupied [Embros theatre in Athens during the debt crisis] may have faced repeated failures, but succeeded in marking a paradigm shift, thereby opening up the space of possibles for alternate ‘instituent’ practices of politics and culture in times of austerity.”