In the wake of concerns about the negative effects of high-sugar and calorie-dense foods on human health, governments have tried to intervene through sugar taxes and changes in food labeling. What changes are most effective in shaping consumer behavior?

For this “visual interview,” we spoke with Nano Barahona, Assistant Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley, who recently examined how a food labeling policy has changed the approaches of both consumers and food producers in Chile. Spanning the fields of industrial organization and public economics, Barahona’s research broadly focuses on studying and quantifying the effects of government policies on individuals’ outcomes and welfare, with an emphasis on health, educational, and environmental policies.

Barahona and his co-authors, Cristóbal Otero, and Sebastián Otero, recently wrote an article about their research for Berkeley Economics, wherein they provided a summary of their recent papers (here and here). “We study the impact of warning labels on nutritional intake in Chile,” they explained. “We partnered with Walmart-Chile, the largest supermarket chain in the country, and accessed scanner data on food purchases between May 2015 and March 2018 in all their supermarkets in the country. We matched each product to its nutritional information, and by connecting transactions to individual shoppers, we were able to compute the impact of the policy on overall nutritional intake.”

What are some of the approaches for addressing consumer food choices through food labeling?

The idea that food labels can improve consumer information — and, therefore, consumer choices — has been floating around for a long time. In the United States, for example, the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act mandated nutrition labeling of all prepackaged foods beginning in 1994. Nevertheless, empirical evidence shows that nutritional fact tables have not been effective at improving consumers’ food choices, mainly because consumers don’t use them or do not understand them.

Since then, governments and international institutions have been exploring numerous policies to improve nutritional choice and combat obesity. An increasingly popular policy is providing simplified information to consumers through front-of-package labels (FoPL), which consist of warning stickers placed on the front of packages to clearly signal to consumers when a given product is unhealthy. Today, more than 35 countries – mostly in Europe and Latin America – have voluntary or mandatory FoPL schemes, compared to only 10 countries in 2010.

Some countries have implemented “nutri-scores,” a quantitative value indicating a healthiness index calculated by an external institution. Other countries have labels in different colors, resembling street lights, with green for healthy products, yellow for intermediate, and red for unhealthy. Other countries, like Chile, have opted for binary labels that warn consumers when a given product is above a specific threshold on some particular critical nutrient, such as sugar, sodium, or saturated fat.

What are the aspects of food labeling in Chile that made it particularly interesting to study, and what’s different about the approach that Chile has taken compared to other countries?

In 2016, Chile became the first country in the world to implement a mandatory nationwide food labeling regulation. Since 2016, more than 25 countries have followed Chile and have either implemented or are in the process of implementing country-wide mandatory food labeling policies.

The following table shows the set of countries that have already implemented or are discussing implementing policies similar to the ones in Chile. All of them include warning stickers for high concentrations of sugar, sodium, and saturated fat. Some, like Chile, include an additional label for products with a high number of calories.

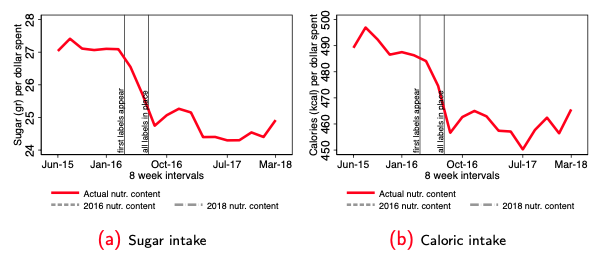

This graph shows how sugar and calorie intake changed as a result of nutrition labeling. How did consumers change their behavior when the new policy went in place?

Through tracking shopping data at Walmart locations in Chile, we documented a sharp overall decrease in sugar and caloric intake of 8.8% and 6.5% per dollar spent, respectively, immediately after the policy was implemented. This reduction, which persisted for the two-year post-policy window in our data, is explained by a combination of demand- and supply-side responses. On the one hand, consumers reacted to the regulation by making healthier choices. On the other hand, companies responded to the regulation by reducing the concentration of regulated nutrients in their products, such as sugar, to push them under the threshold of the regulation. To disentangle these mechanisms, we can zoom into the cereal market.

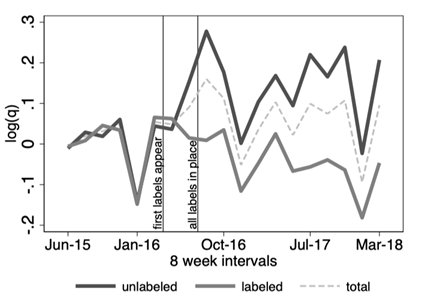

Through tracking sales over time, we found that the policy induced consumers to switch from labeled to unlabeled products. We also found, though, that the total demand for cereal didn’t change much after the policy was implemented. The decrease in demand for labeled products was compensated by a comparable increase in demand for unlabeled products. The figure above shows percentage changes in demand because we used a logarithmic scale. Because the baseline demand was larger for labeled products, the percentage change in demand was smaller. That doesn’t mean that the net change in demand is actually smaller.

You also studied how consumers’ beliefs about these products changed when they saw the new labels. How did consumers respond to this new information, and how did it vary for different kinds of food?

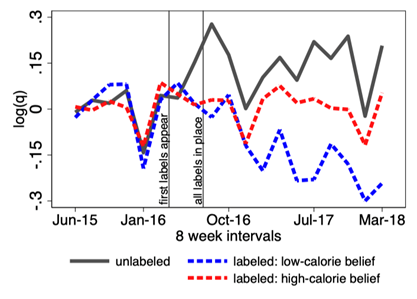

We conducted a survey to elicit consumers’ beliefs about the nutritional characteristics of a set of cereal and soft drink products in the absence of warning labels. We found that, on average, individuals had relatively accurate beliefs about the concentration of sugar in cereal. However, respondents’ beliefs about the calorie concentrations in cereal (calories per gram) were less aligned with reality. Certain granolas, for example, were perceived as being low in calories while they are actually high.

We then split products between those that were believed to be low in calories but were tagged with a high-in-calories label, and those that were known to be high in calories and also received a high-in-calories label. We found that products that were mistakenly believed to be healthy but ended up with a high-in-calories label saw the greatest decline in sales as a result of the policy. These empirical findings suggest that labels are especially effective for products about which consumers are more misinformed.

Under what circumstances were the food labels most effective in changing consumer demand?

Two important features of a product category determine how much food labels affect consumer demand. First, categories in which labeled and unlabeled products are closer substitutes are more likely to show larger substitution effects, which we found in grocery store data. For example, if a high-in-sugar cereal has an alternative available with similar taste but lower levels of sugar concentration, consumers who were misinformed about its sugar content will be more likely to switch than if an alternative wasn’t available.

Second, food labels are more effective in shaping consumer demand for categories in which they are more informative. In the soft drinks category, for example, consumer beliefs about sugar concentration are relatively accurate, mostly because soft drinks are already categorized as either diet and non-diet drinks. When we estimate the effects of food labels on demand for soft drinks, we find that the relative change in quantities sold between labeled and unlabeled products is half that for products in the breakfast cereal category.

How did different consumers respond to the new labels?

We find fairly similar effects of the policy on consumer responses across the income distribution. On the one hand, you might think that richer consumers care more about the healthiness of the products they buy. On the other hand, richer consumers might be better informed about products before the policy was implemented. This is particularly important when we compare food labels to sugar taxes. Lower-income households tend to eat more sugary products. Then, if we impose a high tax on sugary products, we end up with a quite regressive policy that ends up charging low-income individuals more. Food labels, on the other hand, don’t require transfers from consumers to the government. Moreover, if low-income consumers are less informed about the nutritional content of the products, they may benefit more from food labels as they will provide more useful information to them.

How does food labeling compare to sugar taxes and other strategies for encouraging healthier diets?

When we compare food labels to sugar taxes, we find that food labels present both advantages and disadvantages. In categories such as chocolates and candy, in which all products receive labels and are known to be high in what policymakers called critical nutrients (sugars or fats), food labels are less effective at improving diet quality. Other market imperfections, such as lack of self control, can be important drivers of consumer bias in these categories. Sugar taxes may be a better tool for fighting obesity in these cases.

However, in categories where low-socioeconomic status consumers are more likely to prefer sugary products or have more misaligned beliefs about products’ nutritional contents, food labels present distributional benefits over sugar taxes that need to be considered.

Our findings suggest that the optimal policy is to combine food labels with sugar taxes, with higher taxes on categories in which non-informational biases are larger, and lower taxes in categories that are consumed more by the lower-income individuals than they are by higher-income individuals. For example, a sugar tax might be effective in reducing consumption of chocolate or sugar-sweetened beverages, categories for which consumers are already aware of their sugar content. In categories where awareness is lower, such as cereal, food labels can be a more effective policy.

You also studied the supply-side effects of the new labeling system. How did food manufacturers respond?

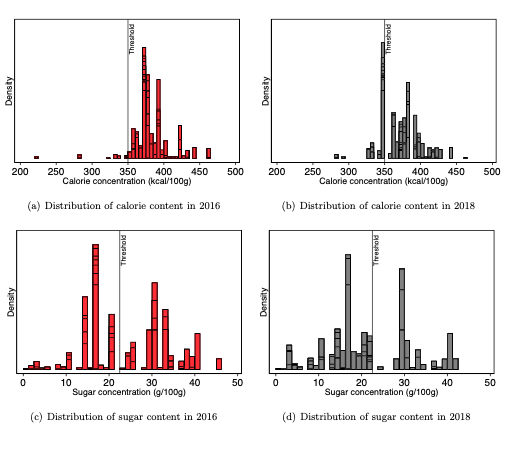

To study how firms responded to the labeling policy, we compared the distribution of nutritional content before and after the policy was implemented. In 2016, before the policy was implemented, 55 cereal products were above the threshold for caloric concentration. In 2018, 13 of those products reduced their concentration of calories to just below the threshold. In economic terms, eight of the products bunched at the threshold of 350 kcal per 100 grams.

We observed a similar pattern when we looked at sugar concentration. In 2016, 27 regulated products were above the threshold. In 2018, nine of these reduced their sugar content to be below the threshold, and six reduced it to between 20 and 22.5 grams of sugar per 100 grams of cereal. This suggests that firms chose to respond strategically to the labeling policy, bunching at the threshold to avoid receiving a label.

This behavior by firms resulted in a net reduction in the caloric and sugar concentration of cereal products offered in the market. The average caloric concentration of products decreased from 383.6 to 372.8 kcal per 100 grams, while the average sugar concentration of products decreased from 21.54 to 19.06 grams of sugar per 100 grams of cereal.

How do the supply- and demand-side effects of this policy compare to each other?

To answer this question, we first needed to find a way of quantifying the net effects of the policy. Consumer and firm decisions changed in many different ways due to the policy. Consumers changed their purchasing decisions due to the new information, and firms changed both prices and nutritional content of products, which impacts consumer well-being. We calculated consumer well-being, a dollar-value measure of people’s happiness, by estimating consumers’ willingness to pay for different product characteristics, and we used this measure to value the net gains of the policy. In other words, we calculated how much a consumer would be willing to pay in order to get this policy implemented.

We first quantify the effects of food labels in the absence of supply-side responses. If companies were not able to change their food formulations or change their prices, we find that the regulation reduces sugar and caloric intake in the cereal market by 6.8% and 0.6%, respectively, resulting in average gains in consumer well-being equivalent to 1.1% of total cereal expenditure, or about $0.28 per year. This is the amount that consumers would be willing to pay in order to have the policy implemented.

Second, we asked what would have happened if firms were not allowed to change the content of their food but could still optimally choose prices. We find that prices of unlabeled and labeled products go up and down, respectively, with average prices remaining relatively constant. Gains in consumer welfare relative to the no-intervention counterfactual are 7% lower than in the absence of supply-side responses.

Finally, we allow firms to optimally reformulate their products to avoid receiving labels. This exercise recovers the full effect of the policy. Overall, we find that products that were tasty but unhealthy became now healthier but more expensive due to higher production costs. Consumer well-being gains under this counterfactual are 48% larger than in the absence of supply-side responses.

What implications does your research have for policymakers?

Our research has important implications for the design of food labeling policies. Policymakers choosing regulatory thresholds for labeling policies should take into account several dimensions. First, it is important to target categories that represent a large share of consumers’ intake of harmful critical nutrients like saturated fats and sugars, such as soft drinks and cereal. Second, thresholds must be set to maximize substitutability within targeted categories, which means that the categories need to have both healthy and unhealthy products that are close substitutes — like cereal, where there are both healthy and unhealthy products, and unlike candy, where all products have similar sugar content. The categories should also be categories where consumers are misinformed about the healthiness of their products. Third, thresholds must be tighter in targeted categories in which reformulation is feasible at a low cost, such as liquids, where replacing sugar by artificial sweeteners is relatively easy. In solid categories such as cookies, reformulation is much harder because sugar acts as a bulking agent that is harder to replace without losing consistency of the product.

Our results also shed light on the importance of combining different policies to tackle obesity. In categories such as chocolates and candy, in which all products receive labels and are known to be high in sugar, food labels are less effective for improving diet quality. Other market imperfections, such as lack of self-control or time inconsistency, can be important drivers of consumer bias in these categories. Sugar taxes can be a better tool to fight obesity in those cases. Consequently, food labels and sugar taxes should be seen as complementary policies rather than incompatible alternatives.