Kaily Heitz, who earned her PhD from the UC Berkeley Department of Geography in 2021, studies how concepts of Blackness and Black culture are deployed in the making and marketing of Oakland, California. Her dissertation, entitled “Oakland is a Vibe: Blackness, Cultural Framings and Emancipations of The Town,” draws on Black feminist geographies and media studies to understand contemporary conflicts over gentrification in “The Town.”

A paper based on this research, Sunflower’s Oakland: The Black Geographic Image as a Site of Reclamation, was published by Antipode, and was awarded the 2020 Clyde Woods Black Geographies Specialty Group Graduate Student Paper Award. Dr. Heitz has worked with Matrix Research Teams in the past, including the Berkeley Black Geographies team. Her research practice involves ethnographic research with United Roots/ Youth Impact Hub, Eastside Arts Alliance, the Black Cultural Zone, and the Business Association of the Black Arts Movement and Business District (BAMBD), archival research, and analysis of public art in and around Oakland.

This interview by Julia Sizek, a PhD candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Anthropology, revolves around images from Kaily’s work that help reveal the arguments of her work.

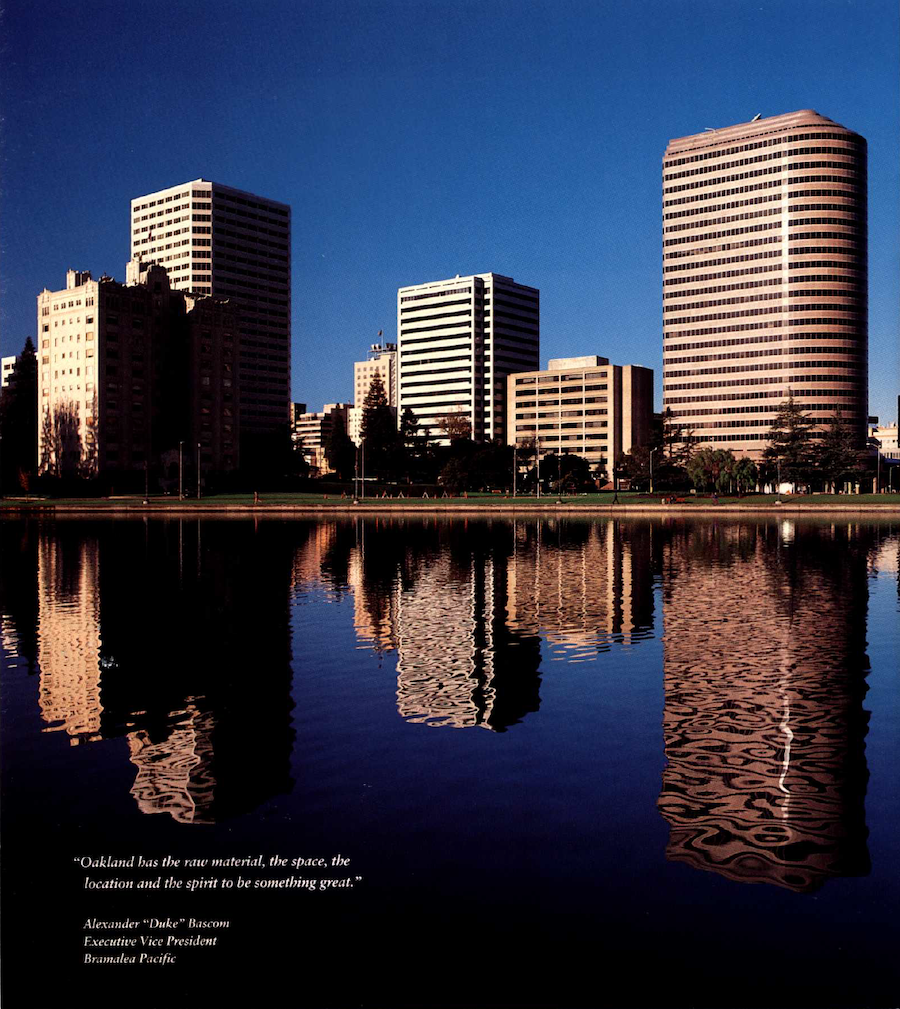

Q: In your dissertation, you track how Oakland has evolved from being, as Gertrude Stein described it, a place with no “there there,” an idea encapsulated in this circa 1995 image from the Chamber of Commerce, to the right. How was Oakland viewed in contrast to the other cities of the Bay Area? How did you decide to start researching Oakland?

I became a geographer because of the way I’ve always been interested in how people form attachments to place, and how these feelings, actions, and attachments also operate through the racialized body, communities, and a sense of place. [Author’s note: racialization here refers to the way that the phenotype and characteristics of people and the spaces they occupy are categorized according to the social construction of race.] The almost palpable sentiment present in and about Oakland, alongside the nomenclature of it being a Black city, was naturally very interesting to me. In terms of tourism and business, Oakland has long been overshadowed by San Francisco, and overlooked by the residential market in favor of the suburbs. So, given the emphasis that people have put on what the city lacks, I was interested in the fact that I loved Oakland, and I was very curious about why I loved it and why others around me – newcomers and locals alike – did as well. This story about the difficult ways that people love and struggle with The Town captured me, and is also part of what marketers are trying to capture when they promote Oakland’s vibe.

Part of this struggle is captured in Oakland’s booster material. Since the 1960s, promotional ads and brochures all seem to suggest that the city should be more materially successful than it has been. Between the post-WWII slump in American city centers and the early 2000s, much of the city’s development was built upon the promised return of White businesses and shoppers to Oakland’s downtown through the development of BART, ancillary highways, and new business districts. One of the biggest stumbling blocks in this plan was an open secret: Oakland’s representation as a Black city in the media. The racist stereotypes about the city, especially in the 1980s and 90s, could be summed up fairly well by a headline from The Argus, in 1991: “The Dumping Grounds.” Oakland was perceived as a place to avoid, a sinkhole for public funds because of the Black and Brown poor, when in fact, it had been floundering due to deindustrialization, federal divestment, and the racially disproportionate effects of the war on drugs. It wasn’t until the early 2000s, with the beginnings of Black displacement and the advancement of gentrification campaigns, that we saw more interest in developing Oakland for business and residential consumers.

In effect, the way that “no there there” has haunted Oakland is part of what makes the city so poignant to study at the personal or affective level. It’s the underdog, and has been the underdog for so long that a culture has built up around this identity of grit, determination, and hustle. This hopeful, sentimental strategy is evident in the caption and framing of this photo. Oakland’s “raw material” — its physical landscape and existing infrastructure – makes up only half of this image. The distorted vision of the city’s skyline in Lake Merritt literally and figuratively reflects a future and a feeling that is not yet wholly tangible.

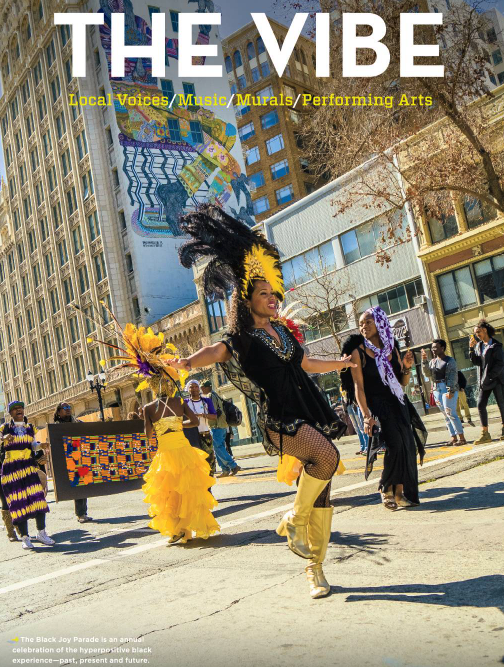

Q: One of the big concepts in your work is “vibe,” a term used by both developers and community organizations to contradictory ends. In this image to the left, for example, we see it used to advertise Oakland. Why did you settle on vibe as a central concept for your research, and how does it help you better understand Oakland?

My research began as an inquiry into the nature of visual representations of place. In my inquiries about what images of Oakland were meant to convey, people reached for terms like “vibe” to explain an almost indescribable feeling of what it meant to be and live in this city. I use vibe primarily as a way of identifying the blurry qualities of affect that we attribute to a place. More specifically, it connects these feelings to the processes of racialization, and the political and economic work of urban development.

Vibe could, I found, be used to describe a number of different cultural and material references, often related to Black and Brown gatherings, businesses, or political histories. In lieu of any particular attraction to bring tourists or new residents to Oakland, the city’s tourism bureau, Visit Oakland, also draws on this kind of affective description; this is often couched within cultural attractions in their tourism brochures. What became most compelling to me about these descriptions was the way that they were often implicitly linked to Black culture or the vague language of “diversity.” For instance, in the 2018 cultural development report issued by the City of Oakland, Mayor Libby Schaaf is quoted as saying that the city’s “cultural vibrancy,” embodied in “our dance moves, our lyrics, our murals, our paintings,” is part of the Oakland’s “secret sauce.” When matched with images like this one of “The Vibe,” and contextualized by the kind of music, dance, and murals Oakland is known for (i.e. blues, West Coast hip hop, murals about social justice and legacies of the city’s Black and Brown communities), it becomes evident that Black people and Black culture are very important “ingredients” in Schaaf’s “secret sauce” and to vibe more generally. The idea of vibe, then, is a contested process of racial, cultural, and capitalistic development. It is at once a feeling, practice, and mode of being that arises from racialized interaction between bodies, structures, and spaces; vibe is also reproduced at the institutional level for economic development, as with these examples from Visit Oakland. For Black communities, being able to repossess a claim to the production of vibe is also a way of repossessing space, capital, and political power in Oakland.

The idea of owning the production of vibe, then, comes with a promise of economic freedom that will always be partial as long as it is bound to a system of racial capitalism and oppression. Community-based groups, like the Black Cultural Zone Collective and members of the BAMBD, are working toward owning spaces that generate desirable and developable forms of vibe, such as businesses, cultural centers, and community plazas. In pursuing this kind of repossession of vibe, these organizations recognize the paradox that exists between their aims for radical liberation, and their means of attaining this goal through the market. This idea forms the basis of what I’ve called “emancipatory framing,” when hegemonic practices and modes of representation are utilized to create spaces of liberation. Liberation for the coalitions with whom I worked in Oakland looks like self-determined acts of ownership over land, community power, and economic systems. These two ideas – of vibe and emancipatory framing – enable an understanding of how important the affective production of Oakland is to conversations about racial justice, gentrification, displacement, and development.

Q: Part of your research includes work with Black Arts and culture organizations, including those in the Black Arts Movement and Business District, an area in downtown Oakland that you describe as a part of the city town that is not particularly “outwardly or visibly Black,” yet “proposes the thesis that Oakland is Black.” How do these contradictions play out on the public stage of city planning?

The story of Oakland’s development since the WWII era is wrapped up in the erasure of the Black poor. For many decades, downtown Oakland was a highly visible site of violence against Black communities that boosters sought to cover up. These days, downtown development plans and cultural plans have taken up the strategy of enhancing the city’s “diversity” – a boon for an elite, aesthete class of White office-workers and home-owners – while downplaying its Blackness or history of Black radical politics. Conversely, by locating a Black business district in the heart of downtown, the BAMBD makes an assertion that Black arts and business have been central to the city’s development and identity, even while Black artists and business owners have been consistently pushed out of downtown spaces.

The question here becomes: is Oakland Black in name and image only (a representational, “diverse” space) or is there power behind its Blackness (ownership and political power)? The latter is what was being fought for in this city by the Black Panthers. The BAMBD community development corporation and its associated members thus face the difficult challenge of utilizing diversity representation politics in order to leverage benefits for existing and future Black businesses and residents downtown. These may come in the form of community benefits agreements, city- and developer-funded grants, and negotiating power when it comes to the city’s downtown development plans.

The danger, I think, is making Oakland too superficially Black in the aesthetic sense without a real community base behind it. The BAMBD unfortunately gets bogged down by being attached to the mechanics of city development. In contrast, collaboratives like the Black Cultural Zone (BCZ) in East Oakland have slightly more flexibility. Rather than trying to make a predetermined district Black, as with the BAMBD, the BCZ is able to occupy and recreate under-utilized pockets of land within East Oakland Black neighborhoods. For instance, where many recent attempts to cultivate cultural districts have occurred in rapidly gentrifying areas adjacent to transit development routes, the BCZ collaborative has developed its own “Liberation Park” in an area that is still predominantly Black in an effort to create a “foothold” for resisting displacement. These strategies, and organizations, ultimately work together in their efforts to leverage vibe toward emancipatory ends.

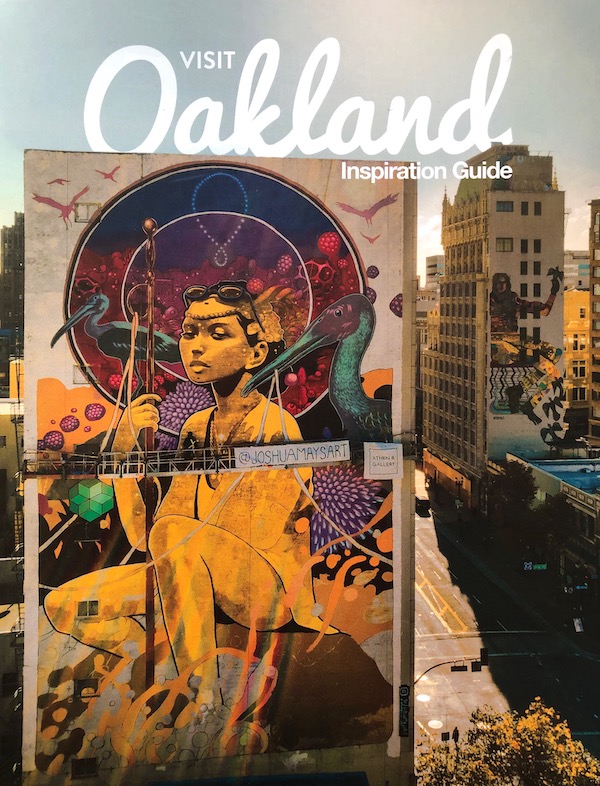

I like thinking about this picture of the Visit Oakland guide alongside the previous image of “The Vibe,” as well as the first image from the Chamber of Commerce. This particular image is the cover of Visit Oakland’s tourism brochure from around 2018, and I think it captures a slightly more specific version of Oakland’s “spirit” that the 1990s relocation guide didn’t quite have the strategy for. Whereas much of the booster material from the early 20th century onward focuses on Lake Merritt, we begin to see more focus on arts and culture with Jerry Brown’s renewed arts-based development focus during his mayorship between 1997-2007.

This particular image was taken near the 19th Street BART station on Broadway. This area of downtown received the brunt of Brown’s redevelopment campaign; he rebranded this part of downtown as “Uptown,” and new luxury condos were constructed here. He also funded more public arts in this part of the city while largely neglecting community public arts projects in East and West Oakland. Here, we get a good sense of the flavor of the ethnically ambiguous (but not White) arts-based diversity development model that Brown initiated.

“The Vibe” photo zooms into a street level view of this same region of Oakland’s “Uptown.” This close-up effect is, I think, part of what Visit Oakland is aiming for in their rebranding campaign from the late 2010s, “See Things from Our Side.” This new logo is a direct counter to the many years of negative stereotypes that prevented people from stopping in Oakland, the “town” on the “other side” of the Bay Bridge. By encouraging visitors to “see things from our side,” Visit Oakland is advertising an experience, in which everyone in Oakland is viewed as an “ambassador” for the city. This kind of decentralization makes up for the fact that there are very few central attractions to bring people to the city. The appeal of Oakland is Oakland itself. To zoom in on the Black Joy Parade on the same stretch of Broadway as these murals demonstrates both the apparent success of Brown’s redevelopment campaign in Uptown and that the experience of Oakland, of Vibe, is intricately connected to the persistence of Black life in this city.

Q: In this image, Sunflower Love, one of the artists you work with, stands in front of a mural by artist Joshua Mays. Who is Sunflower Love, and how did you meet her? How does her work contest or reshape narratives about gentrification and change in Oakland?

Sunflower was a student in the workshop series I taught on smartphone photography at United Roots/ Youth Impact Hub back in 2017. The goal of the course was to bring together the basics of photography, the students’ work on social justice organizations and businesses, and their social media presence. Sunflower was working on her own holistic health care products at the time; for one assignment, she chose to use the idea of “taboo” as a theme unifying her images. Some of the images in this portfolio were of marijuana, or featured a stereotype about Black people. This image (to the right), along with a few others, were the most interesting to me because she included herself alongside murals and graffiti she found around Oakland. Placing herself in the image changed my perception of her photos because suddenly my understanding of what she considered “taboo” (unspeakable, sacred, uncouth) shifted away from the illustrations and toward her body as an unwelcome presence in gentrifying spaces that have been aestheticized as Black. Brandi Summers’ work on “Black aesthetic emplacement” illustrates the way that representations of Blackness, like these murals, may be used to dissociate actual Black bodies from gentrifying spaces. For Sunflower to insert herself into this aesthetic so deliberately is a means of reclaiming not only the aesthetic value of these murals, but also the spaces they are part of developing.

We talked a lot in class about gentrification, stereotypes, police violence, and displacement in Oakland. Sunflower and I also spoke one-on-one about these images and about her relationship to the city. She has struggled with maintaining a stable economic footing in Oakland while keeping a strong social, spiritual and relational connection to the city that she knew while growing up in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This tension comes through in her photos: her regal, assertive poses suggest her power relative to the murals behind her. There is something here of yearning for the expansive imaginary that the murals themselves offer, and the desire for the security that money and power offer. This contradiction feels so alive, so real in the everyday decisions we make about how to live within, uphold, and resist systems of oppression.

This particular image is demonstrative of the way that an aesthetic of Blackness can be pernicious and disempowering for Black artists and entrepreneurs like Sunflower. For instance, I find the way that the figure’s fingers seem to creep up Sunflower’s leg, and the gesture of a second face behind her left shoulder, to be particularly creepy, as if the aesthetic and what it represents about how Oakland has changed is sneaking up on her. And yet, the way her tights appear to blend in with the colors and patterns behind her suggest that she’s a part of this aesthetic – it’s simply gotten away from her. These disembodied images are now eclipsing the embodied experience of Black people in Oakland. Yet, Sunflower seems unfazed by this. She still projects confidence in her stance, despite how small she is relative to Joshua Mays’ figure.

In the second photo (to the left), she does win out over the mural. Here she is larger in the frame, her stance more confident, and the way that her clothing blends in with the mural suggests that she feels a sense of belonging here — to the image, and to the ground upon which she stands. Sunflower’s ownership over this aesthetic I see as a means of claiming vibe for her own economic benefit, as it aims to promote her holistic business. Her series of images are, then, a visual and material process of reclaiming Oakland for herself and her community.

Photo of Kaily Heitz by Alexx Temeña