In partnership with the Office of the Dean of the Division of Social Sciences, Social Science Matrix created this page to aggregate insights about the coronavirus pandemic from the UC Berkeley social science community. UC Berkeley researchers are invited to contribute to this portal, whether by submitting original commentary or links to outside publications to socialsciencematrix@berkeley.edu.

Visit news.berkeley.edu/coronavirus for information on UC Berkeley’s prevention and response efforts related to the COVID-19. The Berkeley Rausser College of Natural Resources has launched a portal with links to research, commentary, videos, and other resources that relate to the coronavirus.

The Center for Studies in Higher Education (CSHE) recently convened a panel focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on international research collaboration. “International knowledge networks are essential for research and research is a core function of universities. All aspects of university work are currently strained by the COVID-19, but international programs, including research collaboration, are especially pressured. These programs have produced some of the most creative and innovative results in many disciplines.” The panel discussed “both the challenges that international research collaboration is facing in the current environment and will describe plans for supporting these efforts and planning for their future post-pandemic.” Participants included: Margaret Heisel, Senior Associate, Center for Studies in Higher Education; David Bogle, Pro-Vice-Provost of the University College London (UCL) Doctoral School; France A. Córdova, an astrophysicist and the 14th director of the National Science Foundation (NSF); Jim Hyatt, Senior Research Associate (CSHE), Vice Chancellor for Budget and Finance and CFO Emeritus; Randy Katz, Vice Chancellor for Research at UC Berkeley; and Tim Stearns, Senior Associate Vice Provost of Research at Stanford University. Watch the video here.

The Center for Studies in Higher Education (CSHE) recently convened a panel focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on international research collaboration. “International knowledge networks are essential for research and research is a core function of universities. All aspects of university work are currently strained by the COVID-19, but international programs, including research collaboration, are especially pressured. These programs have produced some of the most creative and innovative results in many disciplines.” The panel discussed “both the challenges that international research collaboration is facing in the current environment and will describe plans for supporting these efforts and planning for their future post-pandemic.” Participants included: Margaret Heisel, Senior Associate, Center for Studies in Higher Education; David Bogle, Pro-Vice-Provost of the University College London (UCL) Doctoral School; France A. Córdova, an astrophysicist and the 14th director of the National Science Foundation (NSF); Jim Hyatt, Senior Research Associate (CSHE), Vice Chancellor for Budget and Finance and CFO Emeritus; Randy Katz, Vice Chancellor for Research at UC Berkeley; and Tim Stearns, Senior Associate Vice Provost of Research at Stanford University. Watch the video here.

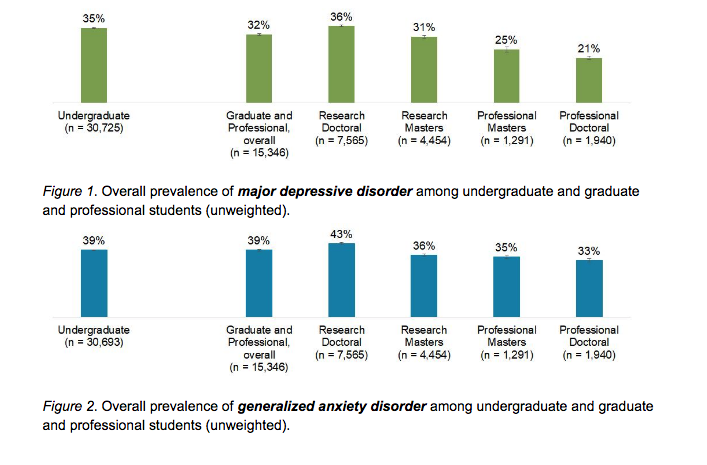

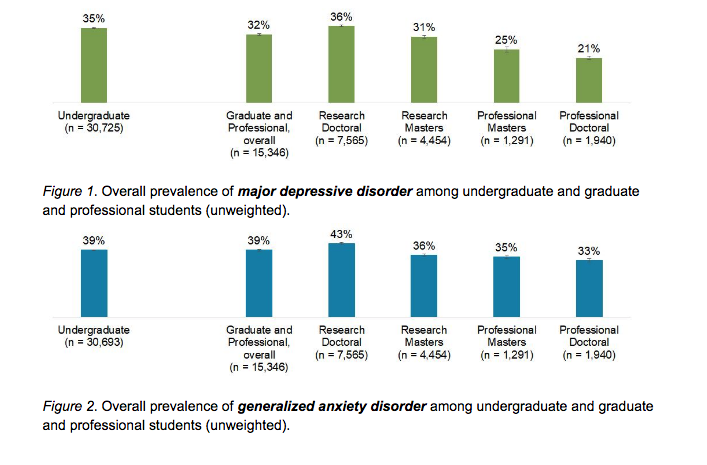

The COVID-19 pandemic is increasing depression and anxiety among college students, with more than a third reporting significant mental health challenges. A recent Berkeley News article by Edward Lempinen cites a new survey co-led by the Center for the Study of Higher Education (CSHE). “The survey of students at nine U.S. public research universities nationwide found that 35% of undergraduates and 32% of graduate and professional students screened positive for major depressive disorder, while 39% of all students screened positive for anxiety disorder, according to the report released on August 18 by the Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) Consortium. The rate of anxiety and depression was more pronounced among low-income students, students of color, LGBTQ+ students and those who are caring for loved ones. ‘As the pandemic continues, universities need to be prepared for a surge of student requests for mental health services in the fall and beyond,” said SERU Consortium Director Igor Chirikov, a senior researcher at CSHE. “Current plans to continue education with remote or hybrid instruction won’t be effective without adequate resources for mental health support programs.'”

The COVID-19 pandemic is increasing depression and anxiety among college students, with more than a third reporting significant mental health challenges. A recent Berkeley News article by Edward Lempinen cites a new survey co-led by the Center for the Study of Higher Education (CSHE). “The survey of students at nine U.S. public research universities nationwide found that 35% of undergraduates and 32% of graduate and professional students screened positive for major depressive disorder, while 39% of all students screened positive for anxiety disorder, according to the report released on August 18 by the Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) Consortium. The rate of anxiety and depression was more pronounced among low-income students, students of color, LGBTQ+ students and those who are caring for loved ones. ‘As the pandemic continues, universities need to be prepared for a surge of student requests for mental health services in the fall and beyond,” said SERU Consortium Director Igor Chirikov, a senior researcher at CSHE. “Current plans to continue education with remote or hybrid instruction won’t be effective without adequate resources for mental health support programs.'”

In a recent essay posted on 3 Quarks Daily, Pranab Bardhan, Professor of Graduate School in the UC Berkeley Department of Economics, examined the impact the pandemic could have on social democracy, particularly in the wake of recent trends like the rise of automation and globalization, the decline of working-class trade unions, and the increase in inequality and insecurity. Bardhan to “looks at the prospects of social democracy in the post-pandemic world, at the strengthening or weakening of pre-existing tendencies in this respect, and at new elements, circumstances and challenges,” noting it should be seen “as neither a straight-forward prediction, nor just a matter of wishful thinking, more a clear-eyed analysis of constraints and opportunities that social democrats are likely to face or have to be prepared for.”

In a recent essay posted on 3 Quarks Daily, Pranab Bardhan, Professor of Graduate School in the UC Berkeley Department of Economics, examined the impact the pandemic could have on social democracy, particularly in the wake of recent trends like the rise of automation and globalization, the decline of working-class trade unions, and the increase in inequality and insecurity. Bardhan to “looks at the prospects of social democracy in the post-pandemic world, at the strengthening or weakening of pre-existing tendencies in this respect, and at new elements, circumstances and challenges,” noting it should be seen “as neither a straight-forward prediction, nor just a matter of wishful thinking, more a clear-eyed analysis of constraints and opportunities that social democrats are likely to face or have to be prepared for.”

Beth Piatote, Associate Professor of Native American Studies, published a fictional story called “Level 8 Risk,” depicting a future world in which immigrants can earn their citizenship by joining the Civilian BioMedical Corps (or CivCo for short), in which they are infected with diseases so they can produce antibodies that are harvested and sold. An excerpt: “Three years after the implant gave me an infection, I’m about to get another one. Another microchip implant, that is, and possibly another infection. I’d call it a level 3 risk. Implant infection was only a level 1 risk last time and I got one, so I’m upping the odds. Esau says it’s good to be prepared, especially with re-entry on the horizon. Re-entry has been on the horizon the entire three years I’ve been here. Every time I get scanned the date pops up: May 1, 2028, embedded in the bar code as 010528. At first, I tried to memorize my whole ID, but the green digits on the screen always disappeared too quickly. Once I caught sight of the date in the sequence, I began to focus on that. And thus I became the date of my discharge, which seems as good an identity as any. It’s called discharge, not release or emancipation, because the Civilian BioMedical Corps (or CivCo for short) was designed to mirror the military structurally if not practically. I used to think of the Army and CivCo as twins, like my brother Saul and me, but CivCo is more like that spoiled step-brother who came along after Uncle Sam got remarried to his much younger second wife.” Read the full piece. Read the full piece (behind a paywall on the SF Chronicle site).

Beth Piatote, Associate Professor of Native American Studies, published a fictional story called “Level 8 Risk,” depicting a future world in which immigrants can earn their citizenship by joining the Civilian BioMedical Corps (or CivCo for short), in which they are infected with diseases so they can produce antibodies that are harvested and sold. An excerpt: “Three years after the implant gave me an infection, I’m about to get another one. Another microchip implant, that is, and possibly another infection. I’d call it a level 3 risk. Implant infection was only a level 1 risk last time and I got one, so I’m upping the odds. Esau says it’s good to be prepared, especially with re-entry on the horizon. Re-entry has been on the horizon the entire three years I’ve been here. Every time I get scanned the date pops up: May 1, 2028, embedded in the bar code as 010528. At first, I tried to memorize my whole ID, but the green digits on the screen always disappeared too quickly. Once I caught sight of the date in the sequence, I began to focus on that. And thus I became the date of my discharge, which seems as good an identity as any. It’s called discharge, not release or emancipation, because the Civilian BioMedical Corps (or CivCo for short) was designed to mirror the military structurally if not practically. I used to think of the Army and CivCo as twins, like my brother Saul and me, but CivCo is more like that spoiled step-brother who came along after Uncle Sam got remarried to his much younger second wife.” Read the full piece. Read the full piece (behind a paywall on the SF Chronicle site).

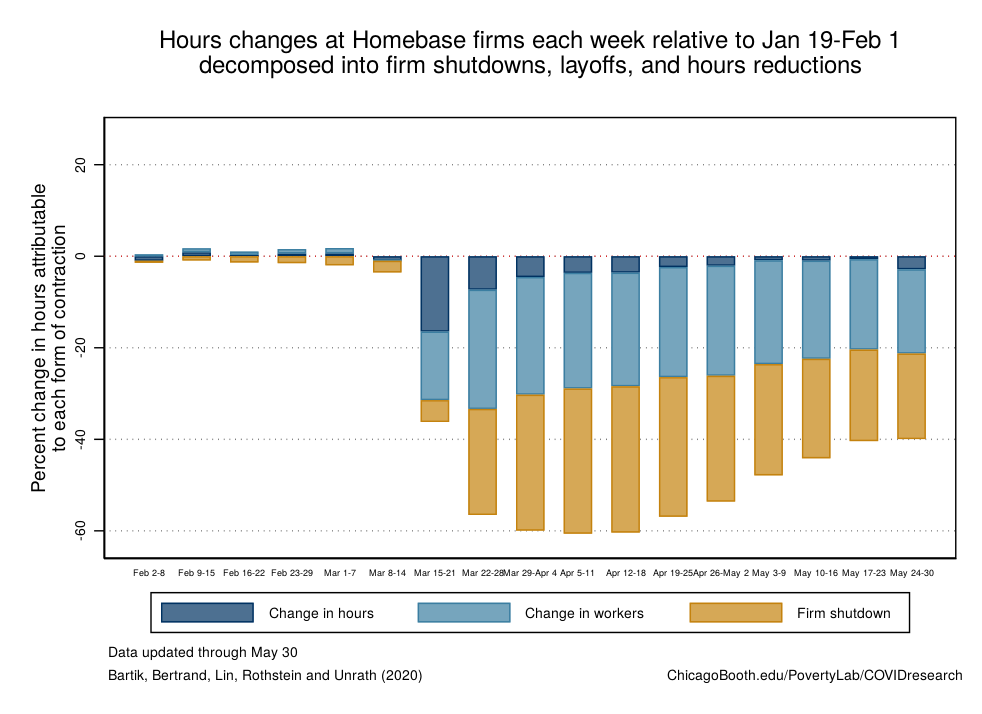

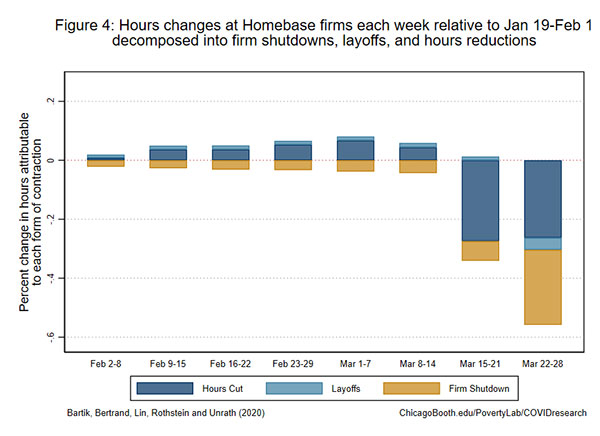

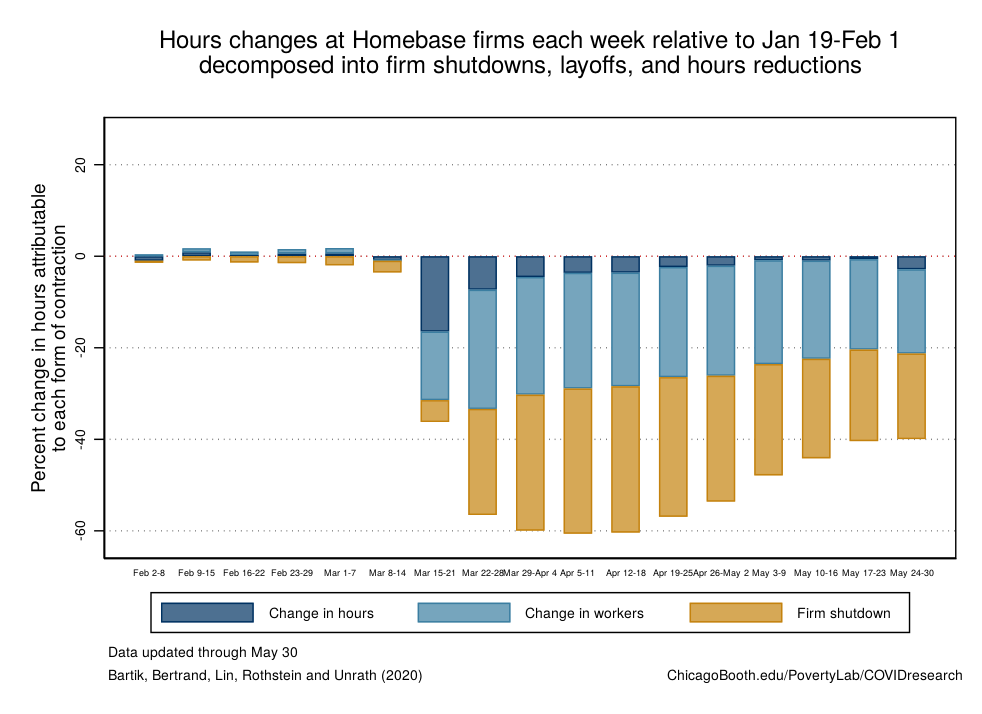

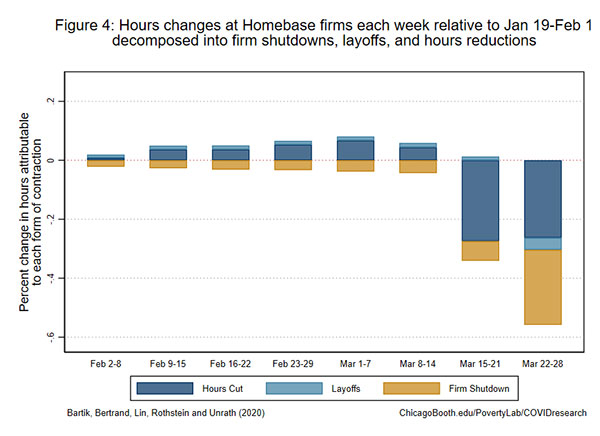

UC Berkeley’s Jesse Rothstein, Associate Professor of Public Policy and Economics, and Matthew Unrath, a PhD candidate at the Goldman School Public Policy — together with researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Chicago — have continued their work measuring the collapse and partial recovery of the U.S. economy, largely using data from Homebase, a private-sector firm that provides time clocks and scheduling software to small businesses. “We use traditional and non-traditional data sources to measure the collapse and subsequent partial recovery of the U.S. labor market in Spring 2020,” they wrote in the abstract. “Using daily data on hourly workers in small businesses, we show that the collapse was extremely sudden — nearly all of the decline in hours of work occurred between March 14 and March 28. Both traditional and non traditional data show that, in contrast to past recessions, this recession was driven by low-wage services, particularly the retail and leisure and hospitality sectors. A large share of the job loss in small businesses reflected firms that closed entirely. Nevertheless, the vast majority of laid off workers expected, at least early in the crisis, to be recalled, and indeed many of the businesses have reopened and rehired their former employees. There was a reallocation component to the firm closures, with elevated nrisk of closure at firms that were already unhealthy, and more reopening of the healthier firms. At the worker-level, more disadvantaged workers (less educated, non-white) were more likely to be laid off and less likely to be rehired. Worker expectations were strongly predictive of rehiring probabilities. Turning to policies, shelter-in-place orders drove some job losses but only a small share: many of the losses had already occurred when the orders went into effect. Last, we find that states that received more small business loans from the Paycheck Protection Program and states with more generous unemployment insurance benefits had milder declines and faster recoveries. We find no evidence so far in support of the view that high UI replacement rates drove job losses or slowed rehiring substantially.”

UC Berkeley’s Jesse Rothstein, Associate Professor of Public Policy and Economics, and Matthew Unrath, a PhD candidate at the Goldman School Public Policy — together with researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Chicago — have continued their work measuring the collapse and partial recovery of the U.S. economy, largely using data from Homebase, a private-sector firm that provides time clocks and scheduling software to small businesses. “We use traditional and non-traditional data sources to measure the collapse and subsequent partial recovery of the U.S. labor market in Spring 2020,” they wrote in the abstract. “Using daily data on hourly workers in small businesses, we show that the collapse was extremely sudden — nearly all of the decline in hours of work occurred between March 14 and March 28. Both traditional and non traditional data show that, in contrast to past recessions, this recession was driven by low-wage services, particularly the retail and leisure and hospitality sectors. A large share of the job loss in small businesses reflected firms that closed entirely. Nevertheless, the vast majority of laid off workers expected, at least early in the crisis, to be recalled, and indeed many of the businesses have reopened and rehired their former employees. There was a reallocation component to the firm closures, with elevated nrisk of closure at firms that were already unhealthy, and more reopening of the healthier firms. At the worker-level, more disadvantaged workers (less educated, non-white) were more likely to be laid off and less likely to be rehired. Worker expectations were strongly predictive of rehiring probabilities. Turning to policies, shelter-in-place orders drove some job losses but only a small share: many of the losses had already occurred when the orders went into effect. Last, we find that states that received more small business loans from the Paycheck Protection Program and states with more generous unemployment insurance benefits had milder declines and faster recoveries. We find no evidence so far in support of the view that high UI replacement rates drove job losses or slowed rehiring substantially.”

A recent New Yorker profile about Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, written by Sheelah Kolhatkar, included insights from Barry Eichengreen, George C. Pardee and Helen N. Pardee Professor of Economics and Political Science, who noted the broad economic challenges the pandemic has wrought, drawn in comparison to crises from the early 20th century. “’I think what’s missing compared to those earlier crises is fully institutional, innovative thinking about how the structure of the economy—of the financial system and of the public sector in particular—needs to change in light of events,” he said. “I have this strong sense that we now need to turn from keeping restaurants and businesses afloat and keeping people on the payroll to thinking about how the economy after the coronavirus is going to look different than it looked before. The crisis is a reminder that the private sector, left to its own devices, doesn’t always manage those challenges optimally. That kind of strategic planning, thinking about what happens next, isn’t happening. And it needs to.” When I asked Mnuchin whether he had thought about initiating bigger structural changes, he paused for a long time, as if struggling with what to say. “I like to study economic history, and I love biographies,” he said eventually. “I think you learn certain lessons from the past. But, again, no situation is ever the same….’ Eichengreen disagreed that the protests had little to do with economic inequality. He noted the vast numbers of young people of all races who were participating, and pointed out that, in addition to anger and frustration about systemic racial inequities, they were likely despairing over their diminishing prospects and the possibility that they would never achieve the living standards of their parents. “People take to the streets in part when they can’t take to the office,” he said. “We know from previous crises, such as 2008 and 2009, that these economic events cast a very long-lived economic scar—that, if you don’t get that internship in the summer between junior and senior year, you’re never going to get on the ladder of employment in that industry. Kids know that. We were already worried about all these things before. People have been reminded of the fragility of their economic prospects and the fragility of their hopes.” Read the full story.

A recent New Yorker profile about Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, written by Sheelah Kolhatkar, included insights from Barry Eichengreen, George C. Pardee and Helen N. Pardee Professor of Economics and Political Science, who noted the broad economic challenges the pandemic has wrought, drawn in comparison to crises from the early 20th century. “’I think what’s missing compared to those earlier crises is fully institutional, innovative thinking about how the structure of the economy—of the financial system and of the public sector in particular—needs to change in light of events,” he said. “I have this strong sense that we now need to turn from keeping restaurants and businesses afloat and keeping people on the payroll to thinking about how the economy after the coronavirus is going to look different than it looked before. The crisis is a reminder that the private sector, left to its own devices, doesn’t always manage those challenges optimally. That kind of strategic planning, thinking about what happens next, isn’t happening. And it needs to.” When I asked Mnuchin whether he had thought about initiating bigger structural changes, he paused for a long time, as if struggling with what to say. “I like to study economic history, and I love biographies,” he said eventually. “I think you learn certain lessons from the past. But, again, no situation is ever the same….’ Eichengreen disagreed that the protests had little to do with economic inequality. He noted the vast numbers of young people of all races who were participating, and pointed out that, in addition to anger and frustration about systemic racial inequities, they were likely despairing over their diminishing prospects and the possibility that they would never achieve the living standards of their parents. “People take to the streets in part when they can’t take to the office,” he said. “We know from previous crises, such as 2008 and 2009, that these economic events cast a very long-lived economic scar—that, if you don’t get that internship in the summer between junior and senior year, you’re never going to get on the ladder of employment in that industry. Kids know that. We were already worried about all these things before. People have been reminded of the fragility of their economic prospects and the fragility of their hopes.” Read the full story.

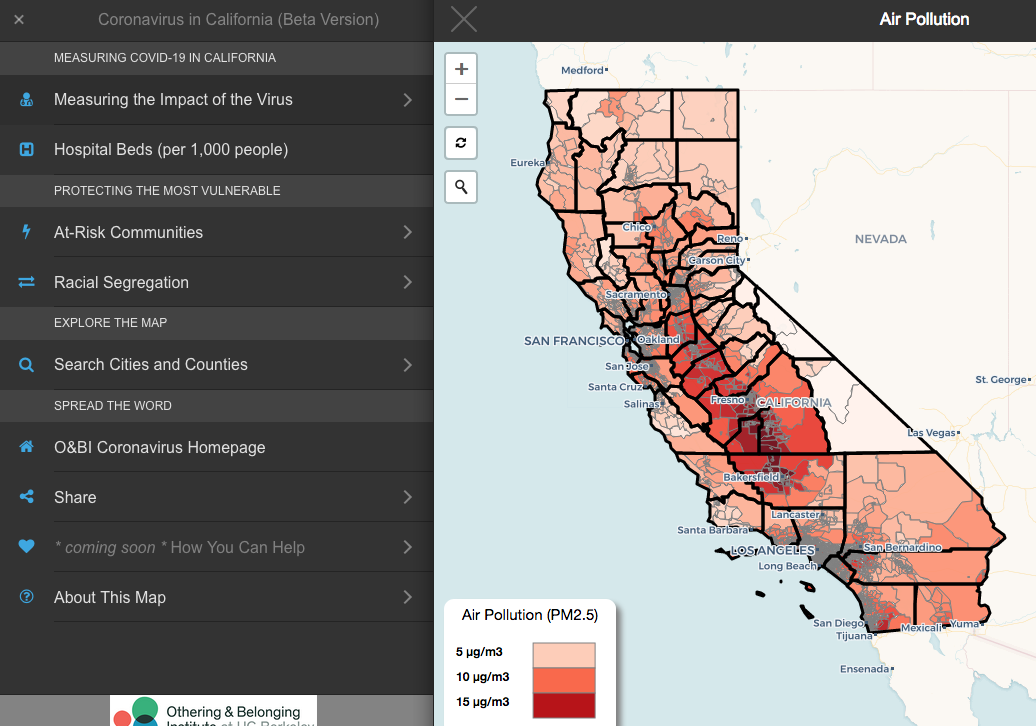

Recorded on June 26, this panel — presented as part of the Berkeley Conversations — featured john powell, Director of the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, Cristina Mora, Co-Director of the Institute of Governmental Studies, and Mahasin Mujahid, Epidemiologist, School of Public Health — exploring the impact of a polarized society on COVID19, especially for vulnerable populations. Mora shared data that revealed significant differences of opinion among Californians from different racial backgrounds and political leanings over questions about the threats posed by COVID-19. “In some analyses, we found that even the most liberal whites expressed less concern about COVID-19 than some of our most conservative Black and Latinx respondents,” she said. Watch the video of the panel here.

Recorded on June 26, this panel — presented as part of the Berkeley Conversations — featured john powell, Director of the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, Cristina Mora, Co-Director of the Institute of Governmental Studies, and Mahasin Mujahid, Epidemiologist, School of Public Health — exploring the impact of a polarized society on COVID19, especially for vulnerable populations. Mora shared data that revealed significant differences of opinion among Californians from different racial backgrounds and political leanings over questions about the threats posed by COVID-19. “In some analyses, we found that even the most liberal whites expressed less concern about COVID-19 than some of our most conservative Black and Latinx respondents,” she said. Watch the video of the panel here.

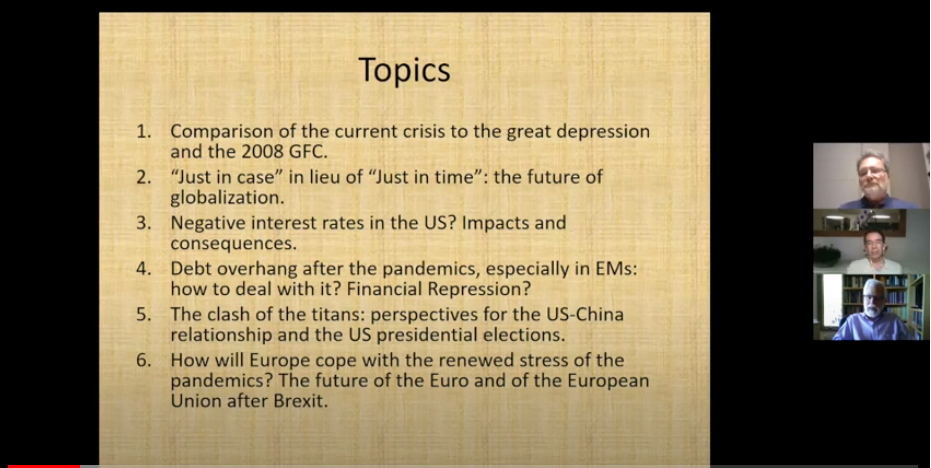

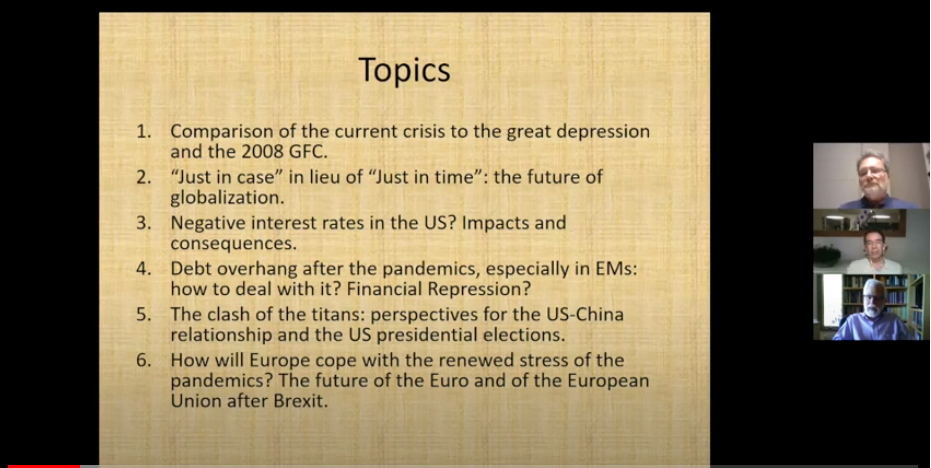

Barry Eichengreen, George C. Pardee and Helen N. Pardee Professor of Economics and Political Science at UC Berkeley, was interviewed by scholars from Economia PUC-Rio (the Department of Economics from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro) about how the current pandemic (and resulting economic crisis) compare to past crises.  “This crisis is fundamentally different from financial crises past, and in the most part fundamentally different from other economic crises past,” Eichengreen said. “People like to compare this crisis with the 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic, which was global to be sure, but also was very different from what we’re going through now. That pandemic started in the midst of World War I, where governments had already ramped up public spending and were on the verge of ramping it back down. That pandemic occurred in a much less urban, industrial world than today, so it spread in urban centers like this pandemic is spreading in urban centers. But economies were less urban then than they are now. Its incidence was different in terms of hitting young people the hardest, rather than older people. All of these comparisons are highly imperfect, highly incomplete, and potentially misleading.”

“This crisis is fundamentally different from financial crises past, and in the most part fundamentally different from other economic crises past,” Eichengreen said. “People like to compare this crisis with the 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic, which was global to be sure, but also was very different from what we’re going through now. That pandemic started in the midst of World War I, where governments had already ramped up public spending and were on the verge of ramping it back down. That pandemic occurred in a much less urban, industrial world than today, so it spread in urban centers like this pandemic is spreading in urban centers. But economies were less urban then than they are now. Its incidence was different in terms of hitting young people the hardest, rather than older people. All of these comparisons are highly imperfect, highly incomplete, and potentially misleading.”

Catherine Ceniza Choy, Professor of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley and author of Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History, was featured in a Vox.com video about “the push and pull factors and the history that led to the large presence of Filipino nurses in the US.” The accompanying article, by Christina Thornell, notes that “Filipino nurses have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus in the US. And that’s because they make up an outsize portion of the nursing workforce. About one-third of all foreign-born nurses in the US are Filipino; it’s been a growing phenomenon for the past 50 years. Since 1960, 150,000 Filipino nurses have come to work in the US. It began with the US colonization of the Philippines under the guise of “benevolent assimilation” and has increased due to a series of US immigration policies. It has resulted in a pipeline that allows the US to draw nurses from the Philippines every time it faces a shortage. But there are factors pushing nurses out of the Philippines too. Check out the video to learn about the push and pull factors and the history that led to the large presence of Filipino nurses in the US.” Professor Ceniza Choy led a Matrix Research Team entitled “Migration, Racialization, and Gender: Comparing Filipino Migration in France and the United States.”

Catherine Ceniza Choy, Professor of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley and author of Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History, was featured in a Vox.com video about “the push and pull factors and the history that led to the large presence of Filipino nurses in the US.” The accompanying article, by Christina Thornell, notes that “Filipino nurses have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus in the US. And that’s because they make up an outsize portion of the nursing workforce. About one-third of all foreign-born nurses in the US are Filipino; it’s been a growing phenomenon for the past 50 years. Since 1960, 150,000 Filipino nurses have come to work in the US. It began with the US colonization of the Philippines under the guise of “benevolent assimilation” and has increased due to a series of US immigration policies. It has resulted in a pipeline that allows the US to draw nurses from the Philippines every time it faces a shortage. But there are factors pushing nurses out of the Philippines too. Check out the video to learn about the push and pull factors and the history that led to the large presence of Filipino nurses in the US.” Professor Ceniza Choy led a Matrix Research Team entitled “Migration, Racialization, and Gender: Comparing Filipino Migration in France and the United States.”

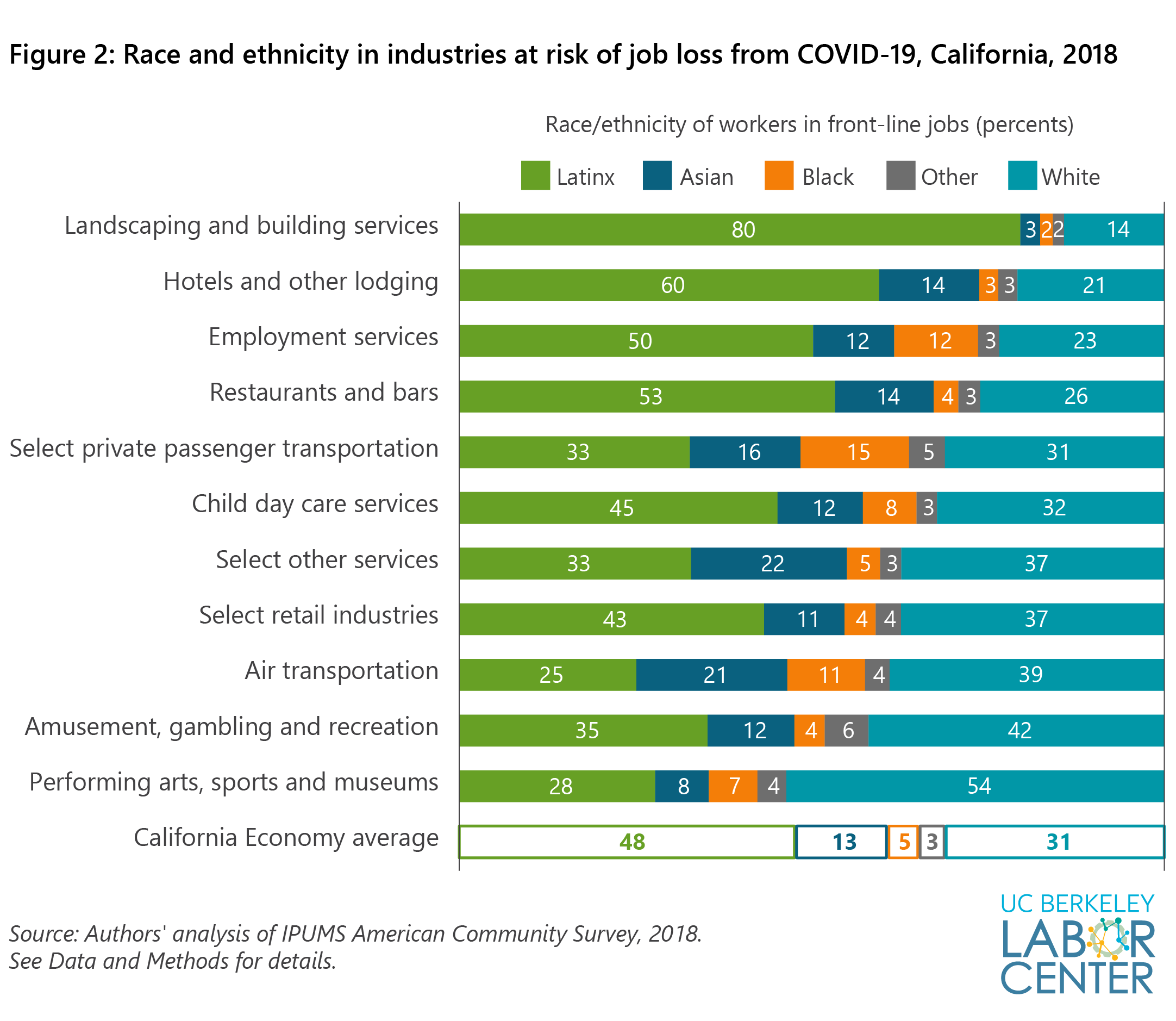

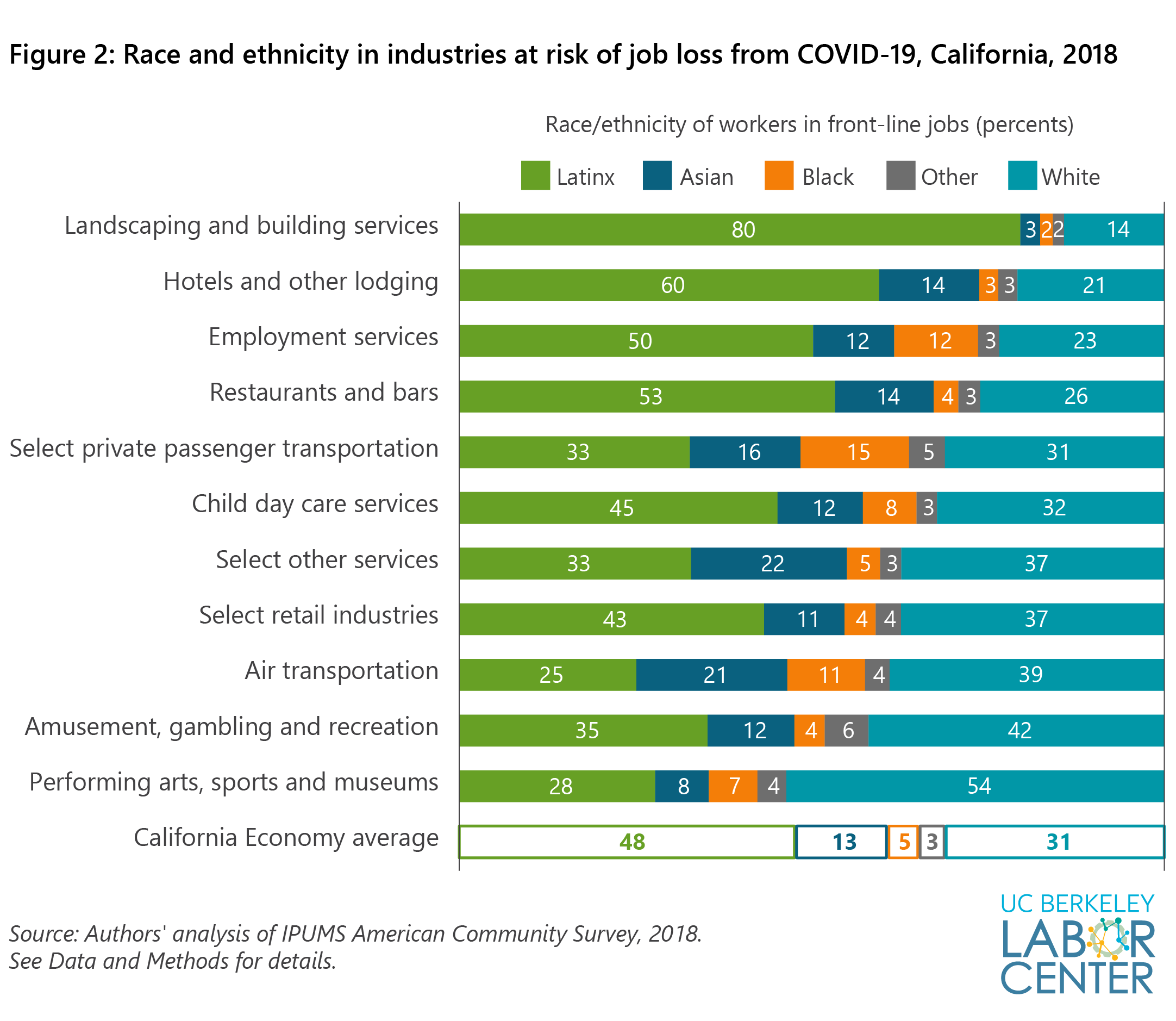

At the federal, state, and local levels, expansive new policy is being developed and implemented to address the COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating effects on workers, businesses, and the economy generally. The UC Berkeley Labor Center is working to provide research on how California specifically is experiencing the pandemic; analysis of what these new policies offer the state’s workers and businesses (and what is still needed); and curated lists of resources, information, and tools for workers and their advocates. Among the findings: more than 40 million Americans have filed for unemployment to date; the CA unemployment rate increased from 5.5% in February to 15.5% in April; just under 29% of California’s workers (including those who are self-employed) have now filed for unemployment insurance; and over 5.5 million initial claims were filed in the eleven weeks between March 15th and May 30th. Visit this page for more information, or download a PDF of the synthesis report.

At the federal, state, and local levels, expansive new policy is being developed and implemented to address the COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating effects on workers, businesses, and the economy generally. The UC Berkeley Labor Center is working to provide research on how California specifically is experiencing the pandemic; analysis of what these new policies offer the state’s workers and businesses (and what is still needed); and curated lists of resources, information, and tools for workers and their advocates. Among the findings: more than 40 million Americans have filed for unemployment to date; the CA unemployment rate increased from 5.5% in February to 15.5% in April; just under 29% of California’s workers (including those who are self-employed) have now filed for unemployment insurance; and over 5.5 million initial claims were filed in the eleven weeks between March 15th and May 30th. Visit this page for more information, or download a PDF of the synthesis report.

In their latest update, researchers at UC Berkeley’s Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE), the California Policy Lab, Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation at Chicago Booth, and the University of Chicago Poverty Lab provided an up-to-date picture of COVID-19’s labor market impact. They are taking advantage of granular data on exact hours worked among employees of firms that use the Homebase scheduling software. Reflecting data through May 23, they found that thirty percent of firms from the baseline sample remain shutdown, down from a high of 45 percent in the beginning of April. Of the firms that ever have shutdown, nearly half (44%) had reopened and remained open. Visit the IRLE’s COVID-19 research and resources page for updates.

In an opinion piece published in Project Syndicate, Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley and a former senior policy adviser at the International Monetary Fund, argues that the protests following the death of George Floyd stemmed in part from the race-based inequality exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. “While it has been widely noted that the social turmoil unfolding in the wake of Floyd’s death may worsen the already-acute COVID-19 crisis, the connection running in the other direction — from the pandemic to the demonstrations — has received far less attention,” Eichengreen wrote. “Without diminishing for a moment the horror of Floyd’s death, the question is: why now?…. It is not incidental that African-Americans work disproportionately in the service sector, where employment has been decimated. It is not incidental that the share of the nonelderly US population lacking health insurance is 1.5 times higher among blacks than among whites. And it is not incidental that the COVID-19 mortality rate is 2.4 times as high among black Americans as white Americans. Even without more images of police brutality, the situation facing many African-Americans, disproportionately affected by the pandemic, was already approaching the unbearable. That is because of America’s threadbare social safety net.” Read Eichengreen’s piece here.

In an opinion piece published in Project Syndicate, Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley and a former senior policy adviser at the International Monetary Fund, argues that the protests following the death of George Floyd stemmed in part from the race-based inequality exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. “While it has been widely noted that the social turmoil unfolding in the wake of Floyd’s death may worsen the already-acute COVID-19 crisis, the connection running in the other direction — from the pandemic to the demonstrations — has received far less attention,” Eichengreen wrote. “Without diminishing for a moment the horror of Floyd’s death, the question is: why now?…. It is not incidental that African-Americans work disproportionately in the service sector, where employment has been decimated. It is not incidental that the share of the nonelderly US population lacking health insurance is 1.5 times higher among blacks than among whites. And it is not incidental that the COVID-19 mortality rate is 2.4 times as high among black Americans as white Americans. Even without more images of police brutality, the situation facing many African-Americans, disproportionately affected by the pandemic, was already approaching the unbearable. That is because of America’s threadbare social safety net.” Read Eichengreen’s piece here.

Writing for Project Syndicate, Pranab Bardhan, Professor of Graduate School at the UC Berkeley Department of Economics — and author, most recently, of Globalization, Democracy and Corruption: An Indian Perspective — argues that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi must do more to support the nation’s poor. “By imposing one of the world’s harshest COVID-19 lockdowns before preparing adequately or consulting with lower levels of government, Modi has inflicted unprecedented damage on India’s economy and on the poor, who live hand-to-mouth at the best of times,” Bardhan wrote. “In general, the government’s response has largely excluded hundreds of millions of daily wage laborers and urban workers. A substantial increase in cash assistance to all these people — with or without bank accounts — would have gone a long way toward boosting aggregate demand. Likewise, the government could have done more to discourage major non-farm employers from shedding their workforce, such as by offering a significant wage subsidy for workers on their payrolls (as many other countries, both rich and poor, have done). The Modi government has also ignored the pressing need for a large-scale transfer of central funds to near-bankrupt state governments…. Given that India, a country of extreme wealth inequality, taxes neither wealth nor inheritance, and under-taxes capital gains and real property, plenty of untapped revenue sources are available. A “corona levy” toward an overhaul of the country’s public-health system would also be timely. Needless to say, vested interests will vehemently oppose any new taxes. But there is no better time than a crisis to overcome such resistance.”

Writing for Project Syndicate, Pranab Bardhan, Professor of Graduate School at the UC Berkeley Department of Economics — and author, most recently, of Globalization, Democracy and Corruption: An Indian Perspective — argues that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi must do more to support the nation’s poor. “By imposing one of the world’s harshest COVID-19 lockdowns before preparing adequately or consulting with lower levels of government, Modi has inflicted unprecedented damage on India’s economy and on the poor, who live hand-to-mouth at the best of times,” Bardhan wrote. “In general, the government’s response has largely excluded hundreds of millions of daily wage laborers and urban workers. A substantial increase in cash assistance to all these people — with or without bank accounts — would have gone a long way toward boosting aggregate demand. Likewise, the government could have done more to discourage major non-farm employers from shedding their workforce, such as by offering a significant wage subsidy for workers on their payrolls (as many other countries, both rich and poor, have done). The Modi government has also ignored the pressing need for a large-scale transfer of central funds to near-bankrupt state governments…. Given that India, a country of extreme wealth inequality, taxes neither wealth nor inheritance, and under-taxes capital gains and real property, plenty of untapped revenue sources are available. A “corona levy” toward an overhaul of the country’s public-health system would also be timely. Needless to say, vested interests will vehemently oppose any new taxes. But there is no better time than a crisis to overcome such resistance.”

In a separate article for the blog 3 Quarks Daily, “Universal Basic Income in Post-Pandemic Poor Countries,” Professor Bardhan weighs the pros and cons of implementing universal basic income (UBI) programs as a response to the COVID-19 crisis. “Over the last decade and a half the world has been subject to many traumatic events—the financial crisis, stringent austerity policies, deep slump in many economies, large-scale job losses, technological disruptions, creeping authoritarianism and ethno-nationalist excesses, increasing incidence of natural disasters (probably attributable to the on-going climate change), agro-ecological distress, mass dislocations, and a whole sequence of epidemics, the coronavirus being the latest. All of this has dangerously exposed the fragility and insecurity of the lives and livelihoods of billions of ordinary people. This has been particularly acute in developing countries, where numerous people live a hand-to-mouth existence even in the best of times, with very little in the form of social insurance. A universal basic income supplement can provide some minimum economic security in those countries, which even under the pressing fiscal constraints may not be unaffordable.” Read the post here.

According to a new research paper published in Nature by UC Berkeley researchers, anti-contagion policies like closing schools and enforcing shelter-in-place restrictions have “signifcantly and substantially slowed” the growth of the COVID-19 pandemic. Led by Solomon Hsiang, Chancellor’s Professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy and Director of the Global Policy Lab, a global team of scholars compiled data on “1,717 local, regional, and national non-pharmaceutical interventions deployed in the ongoing pandemic across localities in China, South Korea, Italy, Iran, France, and the United States.” They then applied “reduced-form econometric methods, commonly used to measure the efect of policies on economic growth, to empirically evaluate the efect that these anti-contagion policies have had on the growth rate of infections…. We estimate that across these six countries, interventions prevented or delayed on the order of 62 million confrmed cases, corresponding to averting roughly 530 million total infections. These fndings may help inform whether or when these policies should be deployed, intensifed, or lifted, and they can support decision-making in the other 180+ countries where COVID-19 has been reported.” A write-up about the research by Berkeley News reporter Edward Lempinen can be found here.

According to a new research paper published in Nature by UC Berkeley researchers, anti-contagion policies like closing schools and enforcing shelter-in-place restrictions have “signifcantly and substantially slowed” the growth of the COVID-19 pandemic. Led by Solomon Hsiang, Chancellor’s Professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy and Director of the Global Policy Lab, a global team of scholars compiled data on “1,717 local, regional, and national non-pharmaceutical interventions deployed in the ongoing pandemic across localities in China, South Korea, Italy, Iran, France, and the United States.” They then applied “reduced-form econometric methods, commonly used to measure the efect of policies on economic growth, to empirically evaluate the efect that these anti-contagion policies have had on the growth rate of infections…. We estimate that across these six countries, interventions prevented or delayed on the order of 62 million confrmed cases, corresponding to averting roughly 530 million total infections. These fndings may help inform whether or when these policies should be deployed, intensifed, or lifted, and they can support decision-making in the other 180+ countries where COVID-19 has been reported.” A write-up about the research by Berkeley News reporter Edward Lempinen can be found here.

African Americans are nearly twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as would be expected based on their share of the population. To understand why, Brandon Patterson, writing for California magazine, a publication for UC Berkeley alumni, interviewed Tina Sacks, a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Social Welfare whose research focuses on poverty, inequality, and racial inequities in health. “The United States is built around structural inequality,” Sacks said. “Those things play out in terms of what’s happening with COVID because black people don’t have as many buffers. Black people are not concentrated in jobs in which they can work from home. They’re also more likely to be in jobs that don’t have paid sick leave. They’re in public-facing jobs that bring them in contact with the public all the time like postal workers or a conductor on BART. That’s one big factor. There are [also] other factors related to health. Black people have been systematically denied medical treatment for hundreds of years. They receive substandard medical treatment. Consequently, black people are much more likely to suffer from chronic health problems that make them more susceptible to COVID and dying from COVID. The conditions in which black people live and work are harmful to our health. Black people are much more likely to live in segregated communities that are fundamentally separate and unequal. They do not have the same institutional anchors that even lower income white communities have in terms of grocery stores, having some place to exercise, and fresh air. So black people’s health is really compromised at every level—and not to mention the psychic trauma that black people endure all the time in terms of police violence and day-to-day exposure to racism. The reasons are numerous but they’re really essentially the same across the country.” Read the full interview here.

African Americans are nearly twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as would be expected based on their share of the population. To understand why, Brandon Patterson, writing for California magazine, a publication for UC Berkeley alumni, interviewed Tina Sacks, a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Social Welfare whose research focuses on poverty, inequality, and racial inequities in health. “The United States is built around structural inequality,” Sacks said. “Those things play out in terms of what’s happening with COVID because black people don’t have as many buffers. Black people are not concentrated in jobs in which they can work from home. They’re also more likely to be in jobs that don’t have paid sick leave. They’re in public-facing jobs that bring them in contact with the public all the time like postal workers or a conductor on BART. That’s one big factor. There are [also] other factors related to health. Black people have been systematically denied medical treatment for hundreds of years. They receive substandard medical treatment. Consequently, black people are much more likely to suffer from chronic health problems that make them more susceptible to COVID and dying from COVID. The conditions in which black people live and work are harmful to our health. Black people are much more likely to live in segregated communities that are fundamentally separate and unequal. They do not have the same institutional anchors that even lower income white communities have in terms of grocery stores, having some place to exercise, and fresh air. So black people’s health is really compromised at every level—and not to mention the psychic trauma that black people endure all the time in terms of police violence and day-to-day exposure to racism. The reasons are numerous but they’re really essentially the same across the country.” Read the full interview here.

Martha Olney, a Teaching Professor in Berkeley’s Economics Department, was interviewed by Darian Woods, of NPR’s “Planet Money,” for a segment focused on “where the money actually goes when the economy crashes.” Olney provided an explanation of the difference between wealth and income. “Part of the question comes from using the word money to mean more than one thing…. In the pandemic, what’s gone is income. In a normal time, one person will spend money, and that becomes the income of the next person, and their spending becomes the income of the next person. And so we have this flow of funds through the economy, and that’s what generates income for a person…. The money didn’t disappear. The $20 bills still exist in that sense. What doesn’t exist anymore is the income that we would have received in March and April and into May as a result of other people buying the things that we produce…. Our wealth is the value of the assets that we own. And so the gold bar in the vault is an asset that we own…. The physical wealth is still there. So the garage is still there. The tools are still there. My computer is still here. And my office, I believe, is still there, although we haven’t been allowed on campus for two months. And so those things still exist, and they still have value.” Listen to the full interview here.

Martha Olney, a Teaching Professor in Berkeley’s Economics Department, was interviewed by Darian Woods, of NPR’s “Planet Money,” for a segment focused on “where the money actually goes when the economy crashes.” Olney provided an explanation of the difference between wealth and income. “Part of the question comes from using the word money to mean more than one thing…. In the pandemic, what’s gone is income. In a normal time, one person will spend money, and that becomes the income of the next person, and their spending becomes the income of the next person. And so we have this flow of funds through the economy, and that’s what generates income for a person…. The money didn’t disappear. The $20 bills still exist in that sense. What doesn’t exist anymore is the income that we would have received in March and April and into May as a result of other people buying the things that we produce…. Our wealth is the value of the assets that we own. And so the gold bar in the vault is an asset that we own…. The physical wealth is still there. So the garage is still there. The tools are still there. My computer is still here. And my office, I believe, is still there, although we haven’t been allowed on campus for two months. And so those things still exist, and they still have value.” Listen to the full interview here.

UC Berkeley economists Jesse Rothstein and Danny Yagan, together with Martha Gimbel, of Schmidt Futures, released research on how the U.S. labor market compares with others during the pandemic. The study “compiles and compares official jobs numbers from seven major countries through April 2020. Post-COVID job losses have varied dramatically across countries. The United States experienced the largest January-to-April rise in unemployment and along with Canada lost over 15% of employment, amounting to 25 million newly jobless U.S. individuals. Germany, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Israel lost only 0.7%-4.4% of employment – equivalent to 18-24 million fewer jobless individuals on America’s population base. Germany and Japan each lost only 0.9% of employment as millions of their workers received assistance while working reduced hours under previously established ‘short-time’ work systems. In contrast, employers in the United States and Canada eliminated jobs altogether as the virus spread. South Korea and Australia share strong travel ties with China but contained their outbreaks quickly, experiencing respective employment declines of only 3.6% and 4.4%. Hence, job losses have been lowest in countries that either contained the virus early or had robust systems for subsidizing jobs at reduced hours.” Read the paper here.

UC Berkeley economists Jesse Rothstein and Danny Yagan, together with Martha Gimbel, of Schmidt Futures, released research on how the U.S. labor market compares with others during the pandemic. The study “compiles and compares official jobs numbers from seven major countries through April 2020. Post-COVID job losses have varied dramatically across countries. The United States experienced the largest January-to-April rise in unemployment and along with Canada lost over 15% of employment, amounting to 25 million newly jobless U.S. individuals. Germany, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Israel lost only 0.7%-4.4% of employment – equivalent to 18-24 million fewer jobless individuals on America’s population base. Germany and Japan each lost only 0.9% of employment as millions of their workers received assistance while working reduced hours under previously established ‘short-time’ work systems. In contrast, employers in the United States and Canada eliminated jobs altogether as the virus spread. South Korea and Australia share strong travel ties with China but contained their outbreaks quickly, experiencing respective employment declines of only 3.6% and 4.4%. Hence, job losses have been lowest in countries that either contained the virus early or had robust systems for subsidizing jobs at reduced hours.” Read the paper here.

The UC Berkeley School of Public Health released a report this month revealing that providers for youth experiencing homelessness should be supported in order to adequately care for those who are unable to shelter in place. The report, titled “On the COVID-19 Front Line and Hurting,” discusses the needs of providers for youth experiencing homelessness in the East Bay as well as of the youth themselves. As reported by Luis Cobian in the Daily Californian, the report was the result of a collaboration between the UC Berkeley Catalyst Group to End Youth Homelessness, sponsored by Innovations for Youth, or i4Y, and the UC Berkeley School of Public Health COVID-19 Community Action Team. ‘Both in Alameda County and in Berkeley, youth homelessness is vastly, disproportionately, African American,’ said Coco Auerswald, UC Berkeley professor and principal investigator of the study, who has been researching youth homelessness for almost 25 years. ‘And that’s in Berkeley, which is by no means a predominantly African American community.’ According to her research, Berkeley’s population is approximately 8% African American, yet 75% of minors who were getting services for homelessness in Berkeley were Black. The report found that what is most needed for youth experiencing homelessness are clean and sanitary public restrooms, shower and laundry facilities, easy access to masks and packaged food, decriminalization of homelessness and access to information and services that can help them shelter in place the best they can. It also found that, to support youth experiencing homelessness, the providers for the youth must also be given funding for disinfectant and hygienic supplies, personal protective equipment including masks, mental health support, hazard pay and on-demand COVID-19 testing for both the youth and providers, regardless of symptoms.” Read the Daily Cal article here. Read the full report, “On the COVID-19 Front Line and Hurting.”

The UC Berkeley School of Public Health released a report this month revealing that providers for youth experiencing homelessness should be supported in order to adequately care for those who are unable to shelter in place. The report, titled “On the COVID-19 Front Line and Hurting,” discusses the needs of providers for youth experiencing homelessness in the East Bay as well as of the youth themselves. As reported by Luis Cobian in the Daily Californian, the report was the result of a collaboration between the UC Berkeley Catalyst Group to End Youth Homelessness, sponsored by Innovations for Youth, or i4Y, and the UC Berkeley School of Public Health COVID-19 Community Action Team. ‘Both in Alameda County and in Berkeley, youth homelessness is vastly, disproportionately, African American,’ said Coco Auerswald, UC Berkeley professor and principal investigator of the study, who has been researching youth homelessness for almost 25 years. ‘And that’s in Berkeley, which is by no means a predominantly African American community.’ According to her research, Berkeley’s population is approximately 8% African American, yet 75% of minors who were getting services for homelessness in Berkeley were Black. The report found that what is most needed for youth experiencing homelessness are clean and sanitary public restrooms, shower and laundry facilities, easy access to masks and packaged food, decriminalization of homelessness and access to information and services that can help them shelter in place the best they can. It also found that, to support youth experiencing homelessness, the providers for the youth must also be given funding for disinfectant and hygienic supplies, personal protective equipment including masks, mental health support, hazard pay and on-demand COVID-19 testing for both the youth and providers, regardless of symptoms.” Read the Daily Cal article here. Read the full report, “On the COVID-19 Front Line and Hurting.”

UC Berkeley’s Jesse Rothstein, professor of public policy and economics, together with Jared Bernstein, chief economist to former vice president Joe Biden, wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post arguing that the federal government should continue to provide stimulus to the economy after the Cares Act is phased out to avoid “scarring effects,” the ongoing damage resulting from economic downturns. “Research has found that even short-lived recessions cause lasting damage to both labor and product markets,” Rothstein and Bernstein wrote. “Workers who are displaced or unable to find jobs at the beginning of their careers are slowed in their progress. It takes them many years to make up lost ground, and they have lower employment and earnings in the meantime, even if the overall economy has recovered….The imperative to avoid scarring also elevates the need to both preserve businesses through virus-induced shutdowns and create fertile ground for start-ups on the other side. Congress has legislated business-preservation programs, but they’ve focused too much on payroll maintenance and too little on helping firms avoid bankruptcy through meeting their non-labor costs. Many European countries have done both — simultaneously ensuring payroll and preventing bankruptcy. Based on our analysis, this should pave the way for quicker recoveries in those countries. It’s not too late to emulate their approach, and a group of Senate Democrats recently introduced a smart, efficient plan designed to equally support workers and businesses as they gradually reopen.” Read the op-ed here.

UC Berkeley’s Jesse Rothstein, professor of public policy and economics, together with Jared Bernstein, chief economist to former vice president Joe Biden, wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post arguing that the federal government should continue to provide stimulus to the economy after the Cares Act is phased out to avoid “scarring effects,” the ongoing damage resulting from economic downturns. “Research has found that even short-lived recessions cause lasting damage to both labor and product markets,” Rothstein and Bernstein wrote. “Workers who are displaced or unable to find jobs at the beginning of their careers are slowed in their progress. It takes them many years to make up lost ground, and they have lower employment and earnings in the meantime, even if the overall economy has recovered….The imperative to avoid scarring also elevates the need to both preserve businesses through virus-induced shutdowns and create fertile ground for start-ups on the other side. Congress has legislated business-preservation programs, but they’ve focused too much on payroll maintenance and too little on helping firms avoid bankruptcy through meeting their non-labor costs. Many European countries have done both — simultaneously ensuring payroll and preventing bankruptcy. Based on our analysis, this should pave the way for quicker recoveries in those countries. It’s not too late to emulate their approach, and a group of Senate Democrats recently introduced a smart, efficient plan designed to equally support workers and businesses as they gradually reopen.” Read the op-ed here.

On June 10, the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA) will sponsor a panel featuring four experts from the CEGA research community to discuss ongoing and completed research that sheds light on the economic toll of the pandemic, as well as the optimal design and targeting of cash transfer programs. Panelists include: Ted Miguel, Oxfam Professor of Environmental and Resource Economics in the Department of Economics at UC Berkeley and Faculty co-Director of the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), who will present new evidence from Kenya demonstrating the economic toll of COVID on poor households; Supreet Kaur, Assistant Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley and CEGA affiliate, who will share research on the impacts and legacy of scarcity and economic shocks in India, with implications for other countries; Paul Niehaus, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, San Diego, who will explain GiveDirectly’s tested social safety net model (unconditional cash transfers), reviewing evidence from Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda; and Josh Blumenstock, Assistant Professor at the UC Berkeley School of Information and Director of the Data-Intensive Development Lab, who will discuss the potential to use machine learning approaches and nontraditional data sources (including mobile phone records) to quickly and effectively target the delivery of social safety net programs. Carson Christiano, CEGA Executive Director, will moderate the panel. Watch here.

On June 10, the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA) will sponsor a panel featuring four experts from the CEGA research community to discuss ongoing and completed research that sheds light on the economic toll of the pandemic, as well as the optimal design and targeting of cash transfer programs. Panelists include: Ted Miguel, Oxfam Professor of Environmental and Resource Economics in the Department of Economics at UC Berkeley and Faculty co-Director of the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), who will present new evidence from Kenya demonstrating the economic toll of COVID on poor households; Supreet Kaur, Assistant Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley and CEGA affiliate, who will share research on the impacts and legacy of scarcity and economic shocks in India, with implications for other countries; Paul Niehaus, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, San Diego, who will explain GiveDirectly’s tested social safety net model (unconditional cash transfers), reviewing evidence from Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda; and Josh Blumenstock, Assistant Professor at the UC Berkeley School of Information and Director of the Data-Intensive Development Lab, who will discuss the potential to use machine learning approaches and nontraditional data sources (including mobile phone records) to quickly and effectively target the delivery of social safety net programs. Carson Christiano, CEGA Executive Director, will moderate the panel. Watch here.

On May 27, as part of the Berkeley Conversations series, researchers from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies (IGS) and the California Initiative for Health Equity & Action (Cal-IHEA) discussed the findings of a recent poll on Californians’ opinions and attitudes related to COVID-19. IGS Co-Directors Cristina Mora and Eric Schickler and Cal-IHEA Director Hector Rodriguez delved into the significance and meaning of the data, and what it might portend for California and the nation in the current context of political polarization and racial inequality. The results point to a wide range of potential political and societal impacts arising from our still-unfolding responses to the pandemic. “One of the biggest trends that stuck out was the racial and class differences we found across the board,” Mora said. “Going into the poll we knew that COVID would exacerbate the racial and class inequality, but we didn’t know how much and in what ways this would be the case…. The results were quite stark. On the one hand, Latinos, Asians, and blacks were all much more likely to say that COVID was a serious threat to their health — much more likely than whites to say that, for example. The perceived threat was already there. But we also found that racial minorities were also more in situations that were more likely to be exposed to COVID. There’s a 20 point difference between whites and Latinos in terms of who is able to work from home safely.” Watch the full conversation here. (Note the video begins around 12:48.)

On May 27, as part of the Berkeley Conversations series, researchers from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies (IGS) and the California Initiative for Health Equity & Action (Cal-IHEA) discussed the findings of a recent poll on Californians’ opinions and attitudes related to COVID-19. IGS Co-Directors Cristina Mora and Eric Schickler and Cal-IHEA Director Hector Rodriguez delved into the significance and meaning of the data, and what it might portend for California and the nation in the current context of political polarization and racial inequality. The results point to a wide range of potential political and societal impacts arising from our still-unfolding responses to the pandemic. “One of the biggest trends that stuck out was the racial and class differences we found across the board,” Mora said. “Going into the poll we knew that COVID would exacerbate the racial and class inequality, but we didn’t know how much and in what ways this would be the case…. The results were quite stark. On the one hand, Latinos, Asians, and blacks were all much more likely to say that COVID was a serious threat to their health — much more likely than whites to say that, for example. The perceived threat was already there. But we also found that racial minorities were also more in situations that were more likely to be exposed to COVID. There’s a 20 point difference between whites and Latinos in terms of who is able to work from home safely.” Watch the full conversation here. (Note the video begins around 12:48.)

In a discussion coordinated by the Institute for South Asia Studies, Raka Ray, Professor of Sociology and South & Southeast Asia Studies and Dean of the UC Berkeley Division of Social Sciences, engaged in conversation with Amita Baviskar, Head of the Department of Environmental Studies and Professor of Environmental Studies and Sociology & Anthropology at Ashoka University, about the impact of COVID on households in India. “Whether it be called lockdown, as in India, or sheltering in place, as in California, the home has assumed particular significance, for it is to this space that we are all confined,” Ray said. “For those of us who have jobs and can work from home, the boundaries between home and work are blurred…. And for those of us who no longer have jobs, home takes on an entirely different meaning as well. And so we want to talk about the effect of COVID on the place that we call home. Home as we know it is not just a place of safety and refuge for us to nurture our families and be nurtured by our families. For many, home is a place of labor. Paid and unpaid, it is a place of pain and it is a place where inequalities are reproduced and produced.” Watch the full conversation here.

In a discussion coordinated by the Institute for South Asia Studies, Raka Ray, Professor of Sociology and South & Southeast Asia Studies and Dean of the UC Berkeley Division of Social Sciences, engaged in conversation with Amita Baviskar, Head of the Department of Environmental Studies and Professor of Environmental Studies and Sociology & Anthropology at Ashoka University, about the impact of COVID on households in India. “Whether it be called lockdown, as in India, or sheltering in place, as in California, the home has assumed particular significance, for it is to this space that we are all confined,” Ray said. “For those of us who have jobs and can work from home, the boundaries between home and work are blurred…. And for those of us who no longer have jobs, home takes on an entirely different meaning as well. And so we want to talk about the effect of COVID on the place that we call home. Home as we know it is not just a place of safety and refuge for us to nurture our families and be nurtured by our families. For many, home is a place of labor. Paid and unpaid, it is a place of pain and it is a place where inequalities are reproduced and produced.” Watch the full conversation here.

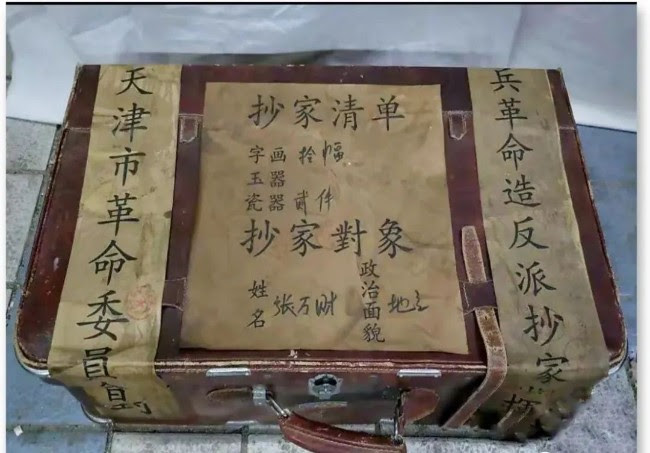

Between April 16 and 20, 2020,the Institute of Governmental Studies (IGS) and the California Initiative for Health Equity & Action (Cal-IHEA), polled 8,800 registered voters about the racialized language President Trump uses when referring to COVID-19. Overall, Californians who approve of the President are not only more likely to blame the Chinese government for the pandemic and shortage of medical supplies but they are also more likely to agree with calling the coronavirus the ‘China virus’. When asked whether it is acceptable for President Trump to refer to COVID-19 as the ‘China virus,’ the ‘Chinese virus,’ or the ‘Wuhan virus’, only 29% of California voters endorse the use of these terms. Of voters who disapprove or strongly disapprove of the President, only 8% believe that his use of these terms is acceptable, compared to 76% of voters who approve or strongly approve ofthe President. As the coronavirus has spread across the U.S., a surge in anti-Asian rhetoric and hate crimes has occurred. Asians have historically been blamed for being disease carriers. According to the Stop AAPI Hate reporting center, this led to over 1,500 reported coronavirus-related racist incidents against Asians in one month since the group began tracking cases in March. Read more about the poll.

Between April 16 and 20, 2020,the Institute of Governmental Studies (IGS) and the California Initiative for Health Equity & Action (Cal-IHEA), polled 8,800 registered voters about the racialized language President Trump uses when referring to COVID-19. Overall, Californians who approve of the President are not only more likely to blame the Chinese government for the pandemic and shortage of medical supplies but they are also more likely to agree with calling the coronavirus the ‘China virus’. When asked whether it is acceptable for President Trump to refer to COVID-19 as the ‘China virus,’ the ‘Chinese virus,’ or the ‘Wuhan virus’, only 29% of California voters endorse the use of these terms. Of voters who disapprove or strongly disapprove of the President, only 8% believe that his use of these terms is acceptable, compared to 76% of voters who approve or strongly approve ofthe President. As the coronavirus has spread across the U.S., a surge in anti-Asian rhetoric and hate crimes has occurred. Asians have historically been blamed for being disease carriers. According to the Stop AAPI Hate reporting center, this led to over 1,500 reported coronavirus-related racist incidents against Asians in one month since the group began tracking cases in March. Read more about the poll.

Brandi T. Summers, assistant professor of geography and global metropolitan studies at UC Berkeley — and author of Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City — published an op-ed in the New York Times arguing that black Americans have long been “trapped in place,” whether by remote, uninhabitable housing projects or constant policy surveillance. “Under the quarantine, much has been made of Americans’ regulated lack of mobility,” Summers wrote. “But our cities have long kept their black residents contained and at the margins…. One might even consider the black experience as a kind of never-ending quarantine — and indeed Jim Crow laws that grew partly out of concerns that black people spread ‘contagion,’ like tuberculosis and malaria, affirmed as much…. We can fight for opening our cities — politically, economically and racially — with the same energy they are putting toward opening our streets. We must create solutions that benefit the masses, not a select few. A true end to quarantine demands ending the quarantining city. It may not be the best we can do, but it’s the least we can ask.” Read the op-ed here.

Brandi T. Summers, assistant professor of geography and global metropolitan studies at UC Berkeley — and author of Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City — published an op-ed in the New York Times arguing that black Americans have long been “trapped in place,” whether by remote, uninhabitable housing projects or constant policy surveillance. “Under the quarantine, much has been made of Americans’ regulated lack of mobility,” Summers wrote. “But our cities have long kept their black residents contained and at the margins…. One might even consider the black experience as a kind of never-ending quarantine — and indeed Jim Crow laws that grew partly out of concerns that black people spread ‘contagion,’ like tuberculosis and malaria, affirmed as much…. We can fight for opening our cities — politically, economically and racially — with the same energy they are putting toward opening our streets. We must create solutions that benefit the masses, not a select few. A true end to quarantine demands ending the quarantining city. It may not be the best we can do, but it’s the least we can ask.” Read the op-ed here.

Nordic countries are regularly cited as exemplars of healthy and resilient societies. A Berkeley Conversations discussion sponsored by the UC Berkeley Haas Center for Responsible Business, the UC Berkeley Department of Scandinavian, the Institute of European Studies, the Peder Sather Center, and Nordic Talks at Berkeley will focus on comparing and contrasting the Nordic public health, economic, and public policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the responses by Denmark and Sweden, and consider learnings that may be drawn by the U.S. Hosted by Dr. Laura Tyson, Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley, the event will feature Dr. Robert Strand, Executive Director of the Center for Responsible Business and leading expert on Nordic sustainable business and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and Dr. Ann Keller, Associate Professor of Health Policy and Management and leading expert on pandemic responses. Watch the conversation here.

A recent panel convened as part of the Berkeley Conversations: COVID-19 brought together experts in political science, public policy, cybersecurity, and law to discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the November 2020 election. Presented by Berkeley Public Affairs, the discussion focused on an array of issues, from presidential approval ratings, the Constitution, election law, unemployment rates to the security of digital voting, the scholars concluded it was still too uncertain to draw any sweeping conclusions. Except that November 2020 will be an election without precedent. “The Trump administration has decided to make an enormous policy and political bet, and the bet is that they can re-open the economy, and the economy will come back in time for the election, and that COVID-19 won’t re-erupt in a way that will either stifle those efforts or kill lots of people,” said Henry Brady, dean of the Goldman School of Public Policy when asked to sum up the next six months. Others, like Bertrall Ross, a professor at Berkeley Law, wondered how the threat of contracting COVID-19 would affect voter turnout, especially among black and Latinx voters who are at higher risk of serious complications if they contract the virus. Philip Stark, a professor of statistics and an expert in election security, wondered if there would be “convincing evidence that the reported winners actually won. Or, are we going to have to take it on faith?” Sarah Anzia, a professor of politics and public policy, noted that there is some hope amid the uncertainty: An messy election could open the door for election law reform, including increased use of vote-by-mail ballots. But on balance, the group said, there is still much to figure out. “Will we be able to hold an election in November that will maximize the ability of people to vote consistent with public health?” asked Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of Berkeley Law. “I don’t think we know right now.” View the video on the Berkeley Conversations website.

A recent panel convened as part of the Berkeley Conversations: COVID-19 brought together experts in political science, public policy, cybersecurity, and law to discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the November 2020 election. Presented by Berkeley Public Affairs, the discussion focused on an array of issues, from presidential approval ratings, the Constitution, election law, unemployment rates to the security of digital voting, the scholars concluded it was still too uncertain to draw any sweeping conclusions. Except that November 2020 will be an election without precedent. “The Trump administration has decided to make an enormous policy and political bet, and the bet is that they can re-open the economy, and the economy will come back in time for the election, and that COVID-19 won’t re-erupt in a way that will either stifle those efforts or kill lots of people,” said Henry Brady, dean of the Goldman School of Public Policy when asked to sum up the next six months. Others, like Bertrall Ross, a professor at Berkeley Law, wondered how the threat of contracting COVID-19 would affect voter turnout, especially among black and Latinx voters who are at higher risk of serious complications if they contract the virus. Philip Stark, a professor of statistics and an expert in election security, wondered if there would be “convincing evidence that the reported winners actually won. Or, are we going to have to take it on faith?” Sarah Anzia, a professor of politics and public policy, noted that there is some hope amid the uncertainty: An messy election could open the door for election law reform, including increased use of vote-by-mail ballots. But on balance, the group said, there is still much to figure out. “Will we be able to hold an election in November that will maximize the ability of people to vote consistent with public health?” asked Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of Berkeley Law. “I don’t think we know right now.” View the video on the Berkeley Conversations website.

An editorial by the San Francisco Chronicle Editorial Board drew upon research from UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation to highlight how California’s housing crisis is worsening during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent study, the Terner Center estimated that more than a quarter-million tenant households in the San Francisco-Oakland area depend on industries hurt by the pandemic, and their median rent amounts to more than 80% of the minimum unemployment benefits they can expect under Congress’ stimulus legislation. “The trouble with letting a crisis linger is that a new one inevitably arrives,” the Chronicle Editorial Board wrote. “California’s leaders have finally waited long enough: The state’s housing shortage has been joined by another disaster, one that compounds and complicates the consequences of the first. The coronavirus pandemic and the strict distancing measures imposed in response administered a financial shock to a state already weakened by housing scarcity. The pathogen arrived to find more than 150,000 of the most vulnerable among us in shelters, tents and doorways, rendering them that much more susceptible to infection and worse. The state’s economy and revenues, for all their strength, have been constrained by the crisis, leaving our government and society less able to sustain the blow. And the opportunity to clean up the mess in good times has finally elapsed, forcing a scramble to manage both crises simultaneously.” Read the full San Francisco Chronicle editorial here.

An editorial by the San Francisco Chronicle Editorial Board drew upon research from UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation to highlight how California’s housing crisis is worsening during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent study, the Terner Center estimated that more than a quarter-million tenant households in the San Francisco-Oakland area depend on industries hurt by the pandemic, and their median rent amounts to more than 80% of the minimum unemployment benefits they can expect under Congress’ stimulus legislation. “The trouble with letting a crisis linger is that a new one inevitably arrives,” the Chronicle Editorial Board wrote. “California’s leaders have finally waited long enough: The state’s housing shortage has been joined by another disaster, one that compounds and complicates the consequences of the first. The coronavirus pandemic and the strict distancing measures imposed in response administered a financial shock to a state already weakened by housing scarcity. The pathogen arrived to find more than 150,000 of the most vulnerable among us in shelters, tents and doorways, rendering them that much more susceptible to infection and worse. The state’s economy and revenues, for all their strength, have been constrained by the crisis, leaving our government and society less able to sustain the blow. And the opportunity to clean up the mess in good times has finally elapsed, forcing a scramble to manage both crises simultaneously.” Read the full San Francisco Chronicle editorial here.

UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies (IGS) has released a poll showing broad public support for protecting farmworkers and providing access to paid sick leave, medical benefits, and full replacement wages if they fall sick with COVID-19. However, these views vary by region, partisanship, trust in the federal government, and attitudes toward immigrants. Between April 16 and 20, 2020 the Institute of Governmental Studies (IGS) and California Initiative for Health Equity & Action (Cal-IHEA), polled 8,800 registered voters about COVID-19. While the majority of employed Californians can work from home, farmworkers continue to work to maintain the country’s food supply during a period of critical need. California farmworkers harvest over a third of U.S. vegetables and two-thirds of the country’s fruits and nuts. However, they remain economically and medically vulnerable to repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Voters in the Central Valley, however, are less likely to support protections for farmworkers despite being the most productive agricultural region of the state and most dependent on farmworkers for their local economy. A quarter of Central Valley voters (25.2%) opposed employer provision of equitable medical and paid sick leave to all farmworkers, regardless of their legal status, if they fall sick with COVID-19, compared to 12.5% of San Francisco Bay Area and 10.4% of Los Angeles County voters. Read the full press release here.

In an op-ed written for The Guardian, Robert Reich, former U.S. Secretary of Labor and now Carmel P. Friesen Professor of Public Policy in the UC Berkeley Goldman School of Public Policy (and author of the new book, The System: Who Rigged It, How We Fix It), examined some of the structural issues that have made the U.S. particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. He points to the nation’s failure to provide universal healthcare or basic sick leave, its weak unemployment system, and its widespread unsafe working conditions. “With 4.25% of the world population, America has the tragic distinction of accounting for about 30% of pandemic deaths so far. And it is the only advanced nation where the death rate is still climbing,” Reich wrote. “So who and what’s to blame for the worst avoidable loss of life in American history? Partly, Donald Trump’s malfeasance. But the calamity is also due to America’s longer-term failure to provide its people the basic support they need.” Read the piece here.