“Social distancing” measures are only effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19 if people actually stay apart from each other. To measure the effectiveness of social distancing, Dennis Feehan and Ayesha Mahmud, Assistant Professors in the UC Berkeley Department of Demography, launched the Berkeley Interpersonal Contact Study (BICS), with seed funding from the Berkeley Population Center.

“Social distancing” measures are only effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19 if people actually stay apart from each other. To measure the effectiveness of social distancing, Dennis Feehan and Ayesha Mahmud, Assistant Professors in the UC Berkeley Department of Demography, launched the Berkeley Interpersonal Contact Study (BICS), with seed funding from the Berkeley Population Center.

“By the start of April 2020, the majority of people living in the United States were under orders to dramatically restrict their daily activities in order to reduce transmission of the virus that can cause COVID-19,” Feehan and Mahmud wrote in the abstract to a paper presenting their initial findings. “These strong social distancing measures will be effective in controlling the spread of the virus only if they are able to reduce the amount of close interpersonal contact in a population. It is therefore crucial for researchers and policymakers to empirically measure the extent to which these policies have actually reduced interpersonal interaction. We created the Berkeley Interpersonal Contact Study (BICS) to help achieve this goal.” We interviewed the scholars to learn about their paper, which can be found here. (Note the paper has not been peer-reviewed.)

The BICS is focused on understanding how “social distancing” measures are affecting human-to-human interaction. What have you found so far?

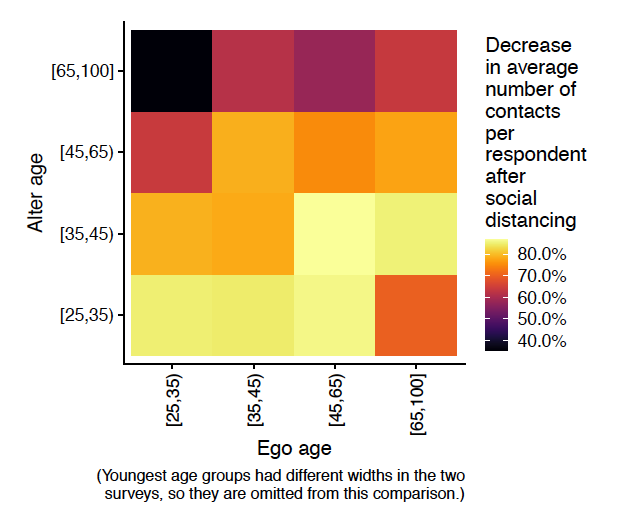

We’ve found that levels of human-to-human interaction are very low in the U.S. now. It’s a little hard to make a precise comparison to the time before social distancing, because no national survey has collected exactly this information previously. But we can compare to some studies that collected similar information, and that comparison suggests that there is something like 70% less interaction now, as compared to business as usual. This estimate in the reduction of contacts is in line with findings from the U.K. (see Jarvis et al. 2020).

Have you seen any notable trends in the data by age, geography, or other variables?

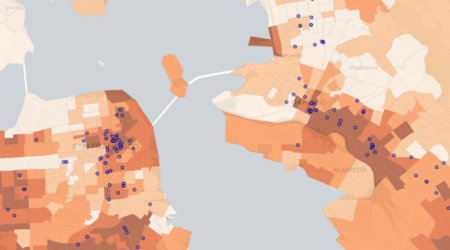

The first set of responses we’ve analyzed comes from March 22 to April 8th. In that time period, we found that interaction was low across the board. The strongest predictor of the number of contacts, by far, is a respondent’s household size. There’s also some evidence that males have higher rates of non-household contacts. We conducted some interviews targeted at a few specific cities: New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, Atlanta, Phoenix, and Boston. We didn’t find that any of those cities had notably high contact rates, but we didn’t have a big enough sample size to detect differences between the cities very precisely.

You wrote in the paper that it was surprisingly hard to find pre-existing data focused on numbers of human interactions. Why do you think this was the case?

Most of the research that has previously studied interpersonal interaction has taken place in Europe. So there’s a fair amount of data out there, but almost none of it applies to the national U.S. population. Detailed information is also difficult to capture using a purely survey-based method. The studies conducted in Europe used diary studies, where respondents were asked to write down details about their contacts in the previous day. These studies are more challenging to conduct than surveys, and there have only been a limited number done globally.

Can you briefly explain the prior research that you used to compare the current data?

Can you briefly explain the prior research that you used to compare the current data?

A lot of my (Dennis’s) work has been about how researchers can sample people and ask them to report about other people who they are connected to through different kinds of personal networks. This is important in demography, because we’re often interested in trying to learn about people we can’t interview. For example, to try to estimate death rates, you have to learn about how many deaths there are in a population — but you can’t sample and interview dead people. So one way to try to learn about dead people is to ask living people about others they know who have died.

In the Facebook study, the question was: how can researchers interview people online, but still make estimates about populations that are not exclusively online? As part of that study, we asked questions that were based on contact networks. So we collected information about interpersonal contact during business as usual; we just didn’t know that it would be useful a few years later, when we needed to understand contact patterns during a pandemic.

What lessons do you expect or hope policymakers will be able to take away from this project?

This first round of data collection helps to quantify just how low person-to-person interaction is under social distancing policies. Our hope is that, as we collect more data over time, we’ll be able to see whether or not adherence to these social distancing policies is being maintained.

What lessons might social scientists take forward from your study, or from social distancing in general?

There’s a lot of great work being done on how to use big data sources — like Facebook or cell phone data — to understand movement and interaction during the pandemic. But it’s not always clear how those signals should get incorporated into models of disease transmission. We’re planning to combine information from the surveys with some of the metrics coming from these big data sources. So, the idea is that surveys like these can help translate big data signals into the quantities that go into disease models.

How long do you plan to keep this research going into the future?

We’re hoping to keep collecting data for the next several months, at least. It will be important to see how person-to-person interaction changes over time. We have some seed money for this project, but we’re still trying to find more funding. So if anyone is interested in funding this sort of work, please contact us.