At the intersection of the War on Terror and the Anthropocene lies Salar Mameni’s concept of the Terracene, which describes the co-emergence of these two terms as a means to understand our contemporary social and ecological crises. Mameni, an Assistant Professor in the department of Ethnic Studies at University of California, Berkeley, is an art historian specializing in contemporary transnational art and visual culture in the Arab/Muslim world, with an interdisciplinary research focus on racial discourse, transnational gender politics, militarism, oil cultures, and extractive economies in West Asia. They have published articles in Signs, Women & Performance, Resilience, and Al-Raida Journal, among others.

In this visual interview, Julia Sizek, Matrix Content Curator and a PhD candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Anthropology, talked with Professor Mameni about their research, working with select images of art discussed in their forthcoming book, Terracene: A Crude Aesthetics.

The concept that you propose in your book, the Terracene, foregrounds the War on Terror as necessary for understanding not only our contemporary political crises, but also our contemporary ecological crisis. Describe your concept, and what it adds to our understanding of the links between terrorism and environmental issues.

My book coins the term “Terracene” in order to bring attention to the role of militarism in enacting the ongoing ecological crises we currently face. I insist that contemporary forms of warfare – such as the infamous War on Terror – are concurrent with and continuations of settler colonial land grabs and habitat destructions that have created wastelands across the globe. In their initial timeline for the Anthropocene, scientists traced the origins of this new epoch to technological innovations in early 19th-century Europe that brought about industrialization. In my view, this is an inadequate historiography that does not take into account longer histories of European settler colonialisms, as well as the ongoing role of militarism in maintaining wastelands. The term “Terracene” is a way of highlighting the terror that is tied to the current geological timeline.

Terror, however, is not the only idea I intend to highlight with the notion of the Terracene. I also take advantage of the sonic resonance of “terr” (meaning earth/land) in the word “terror” in order to direct our attention to the significance of thinking with the materiality of the earth itself. In my work, I consider this through toxicity of militarism and extractive economies, which turn the earth itself into a weapon that continues to poison even after the troops and the industries have receded. Scholars of environmental racism often highlight the dumping of toxic waste on lands inhabited by racialized, poor, and devalued communities. My book emphasizes the production of “terror” out of “terra,” which can mean the weaponization of the earth itself. Yet, I believe that the very shift of attention to the earth’s many potentialities can also allow for conceptualizing futures out of toxic wastelands. For me, new theories are only useful if they do not simply mount a critique of systems of oppression but also offer new imaginaries as foundations for future directions. Much of my book is attentive to materialities and thought systems that do not align with scientific conceptualizations of ecological thinking as a way of opening up new modes of thought.

Part of the reason you relate the Anthropocene and War on Terror is because of their coeval histories. Aside from emerging during the same era, how are the histories of these two concepts — terrorism and the Anthropocene —related?

Yes, the so-called War on Terror, as well as the scientific notion of the Anthropocene, were both popularized in 2001, each proposing a new way of conceptualizing the globe. What is fascinating to me is how each of these ideas revolves around an antagonist: the terrorist in one case, and the Human (Anthropos) who caused climate change in the other.

The question I raise in the book is this: why is it that the term “terrorist” cannot be applied to the Human who has caused deforestations, temperature rise, and oil spills, making the globe uninhabitable for endangered species, as well as threatening the livelihood of multi-species communities globally? Why is the notion of the “terrorist” instead reserved for those who protest the building of oil pipelines on Indigenous lands, or those who resist settler colonialism in places such as Palestine? This tension brought me to see that the idea of the Human (Anthropos) continues to be limited to those engaged in settler colonial ventures, those who are protected against the “terrorist” through the security state.

What do you think the study of art history can bring to the Anthropocene, which is often described through science?

Great question! The book argues that “science” is a provincial worldview that has displaced a plethora of diverse thought systems that are in turn called “art” (or “myth” or “superstition” or “religion”). So my first approach in the book is to question the very art/science divide that disallows those deemed non-scientists to participate in knowledge production. Non-scientists have of course included very large groups, such as women, non-Western knowledge producers, and non-human intelligent beings. This vast array of intelligence left out of “science” says much about the limits and hubris of scientific thought. My book opens up space for artists who think beyond the reaches of scientific ecologies. A part of the book, for example, is dedicated to ecologies of ancient deities. For instance, I consider Huma, the Mesopotamian deity who has been conjured and resurrected by the contemporary Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari (Fig. 1).

As the artist explains, this is the deity of temperatures. Huma’s body is multi-layered and mutative. It has three horned heads, a torso hung with large breasts, and two snake-like tails. Huma is multi-species and multi-gendered and is the deity that rules temperatures. In a time of temperature rise, wildfire, and fevers brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, Huma is the deity to conjure. Indeed, Allahyari conjures her as a protector, but also builds her out of petrochemicals, the plastic used in 3D printers.

I also take seriously the intelligence of non-human phenomena such as oil. In the book, I consider images of explosions at a Southern Iranian oil field, as documented by the Iranian filmmaker Ibrahim Golestan in a film called A Fire! (1961) (Fig. 2).

Rather than thinking about the human triumph of putting out the explosive fire, which took 70 days to extinguish, I consider the intelligence of petroleum that refuses to be extracted from bedrock. I call this human/oil relationality “petrorefusal” in order to call attention to the unidirectional master narrative of extraction. What would it mean, for instance, if we understood explosions as petroleum’s refusal to leave the ground? Would engaging such a refusal mean an end to extractive practices at the current industrial-capitalist scale?

Though you are an art historian, you are attentive to the limits of the visual as a mode of sensing the world. How do you bring other modes of sensing into your work, and how does this shape your approach to art history, which is often imagined as a visual discipline?

Yes, the dominance of the visual within traditions of art history cannot tackle the rich sensorial relations that ecological thinking needs. In the examples of the artworks I cite above, for instance, my theories do not arise from the visual aspects of the works alone. In the case of Huma, a visual reading would miss the spiritual and ethical significance of the deity’s conjuring. Instead, my reading of Huma engages with the object’s deep time, a time that dissolves its plastic materiality into the microbial temporality of oil’s production. In this sense, the sculpture is not simply and statically visual or coeval with our present moment. If we focus on the time of oil and plastic, the sculpture moves into a performative, mutative flux of multi-species organisms across temporalities that are beyond our own. The book as a whole treats the visual as embedded within (and inseparable from) multiple sensorial experiences.

How does art add to our understanding of the Terracene?

I coined the term Terracene as a critique of the notion of the Anthropocene. It is meant to question the centering of a destructive Human (Anthropos) at the core of a planetary story. In this sense, I probe the narrative structure of this scientific story of the Anthropocene — a story that is proposed to be a fact. Usually, storytelling is understood to belong to the domain of arts and humanities. By definition, stories are not checked for factual accuracy, but engaged with at the level of the creative imagination. This is precisely what gives stories their power. Stories can build alternate worlds and offer alternatives to how we perceive reality to be. So if the Anthropocene is a story, then surely other stories can be told. The Anthropocene story is a story of the destructive human, which is why I propose that it is better called the Terracene.

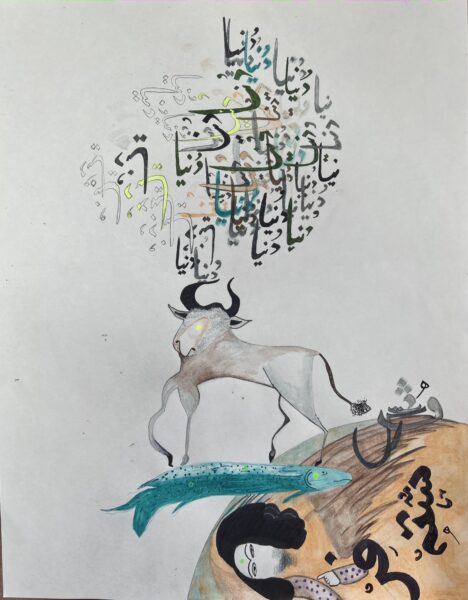

What if we began to tell creation stories at the moment of planetary destruction? Indigenous cultures across the world have creation stories that have been vehemently suppressed by destructive (settler) colonial knowledge productions and worldviews. In the book, I make a case for ethical engagements with subjugated forms of knowledge that offer alternatives to thought systems that have brought the Terracene into being. One such story I relate in the book comes from my own vernacular Islamic culture that imagines the world as a sacred mountain balancing on the horns of a bull, the bull standing on the back of a fish, and the fish, in turn, being held up by the wings of an angel.

I argue that such a creation story emphasizes the inter-relatedness and inter-reliance of all things. The world hangs together in a fine balance, with every creature mattering to its overall existence. Art, in this sense, is not an alien other to science, but an equal participant in the creation of worlds we inhabit.