How did the telegraph change the environment? While scholars have typically examined how the telegraph changed communication, Sophie FitzMaurice, a PhD candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of History, argues that the telegraph was both dependent upon and constrained by the material world during its heyday in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Her research reveals the flip side of US imperial expansion by showing how this novel technology reshaped the environment.

In this visual interview (an interview accompanied by images related to a scholar’s research), we spoke with FitzMaurice about a specific aspect of the telegraph’s materiality: how poles were produced, and how woodpeckers responded to the concomitant disappearance of forests and the rise of telegraph lines.

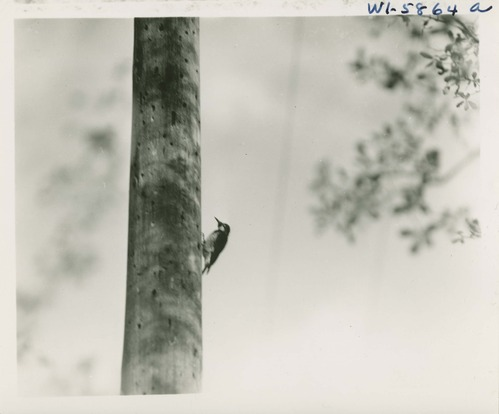

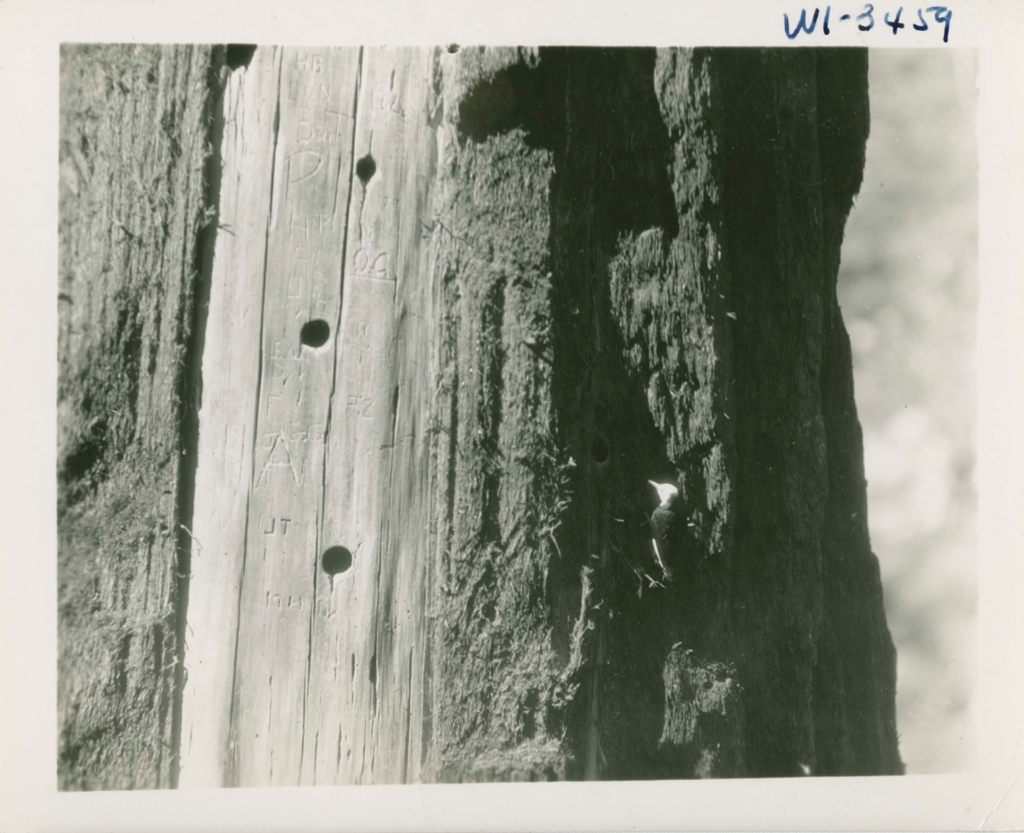

Q: This image provides us with a rare shot of a woodpecker in action — that is, pecking on a telephone pole. At the time, what did scientists think about woodpeckers and their impacts on human industries, and how did they track them?

Nineteenth- and early 20th-century scientists thought of birds as part of the balance of nature, which was conceptually divorced from the world of technology and human industry. The balance of nature paradigm held that every species had a unique, perhaps divinely ordained role that did not change over time. Although scientists believed that humans could throw nature out of harmony, nature itself (including birds and insects) had no capacity to affect human industry or technology.

Scientists who studied birds therefore mostly focused on birds’ role in agriculture, and lacked a conceptual framework to analyze woodpeckers’ impact on technology. The core methodology at the Bureau of Biological Survey (today’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) was stomach content analysis; this method was used to determine which birds were “injurious” to agriculture and which were “beneficial.” On the basis of these findings, scientists made recommendations to farmers and local authorities on which species to encourage and which to discourage or kill. Since woodpeckers ate pest insects, they were considered “beneficial” species, but the damage they caused to utility poles challenged the notion that stomach content analysis alone could be used to determine the economic impacts of birds. Wood does not show up in woodpeckers’ stomachs, since woodpeckers do not eat wood; they drill holes in wood to access insects or to build nests, but they do not eat the wood itself.

This image is dated to 1935, so it was taken at the tail end of economic ornithology, when ecological theory was on the rise. Scientists were beginning to look beyond feeding habits to think about how birds fit into a broader organic community.

How did these attempts to track woodpeckers fail, and how did you try to find these woodpeckers in the archives, where they may not leave a trace?

Before the rise of ecological theory, scientists lacked a conceptual framework to understand how habitat change (including deforestation, to which telegraph construction contributed) might impact woodpecker behavior. At first, very few scientists recognized the correlation between habitat change and woodpeckers’ use of telegraph poles. Over time, they did begin to recognize that woodpecker damage to poles was a problem, and one that could not be understood through stomach analysis. By pecking into and structurally weakening poles, woodpeckers demonstrated conclusively that the nonhuman world could impact human technology and the built environment, and this realization helped drive changes in scientific methodology and government policy.

Woodpeckers don’t tend to show up in the traditional sources of technology history, such as business records and legal contracts. In my research, woodpeckers show up in the archives via the observations of people who worked with utility poles — such as telegraph linemen, superintendents, and pole suppliers — as well as in the publications of scientists and government officials who were called on to address the problem of woodpecker damage.

By integrating non-traditional, vernacular, and scientific sources into the study of technology, I hope to bridge the boundaries between sub-disciplines and shine light on previously overlooked aspects of the telegraph’s materiality. We can also draw inferences about woodpeckers’ historic impact on telegraph poles by looking at how woodpeckers interact with utility poles in the present day. Here in California, you don’t have to look far to see an acorn woodpecker working away at a utility pole. By foregrounding woodpeckers in my research, I show that technology does not operate in a vacuum devoid of animals and insects, and that non-human animals have long been actors in the human world.

Let’s backtrack from woodpeckers’ impacts on finished telegraph poles to understand what the telegraph was and what it represented in the late 19th century. How did people think about the telegraph, and how did it revolutionize communications?

Before the invention of the electric telegraph, information could travel only as fast as people could move (though there were a few exceptions, such as smoke signals and semaphore). In 1860, before there was a telegraph line across the continent, the fastest a message could travel from Missouri to California was ten days, and it took over two weeks to send a message across the Atlantic. The telegraph changed all of that. It was now possible to send messages across thousands of miles in a fraction of a second.

In addition to this, communication was no longer directly dependent on movement. Historians have described this as a “quantum leap” in communications. I accept that characterization to an extent, but concentrating on the speed of sending a message has caused historians to overlook the huge amount of labor, materials, and energy that went into making this apparently instantaneous and disembodied communication possible. Such broad characterizations of the telegraph also erase the fact that its expense made it inaccessible to most Americans. It was a “quantum leap,” but only for the wealthy.

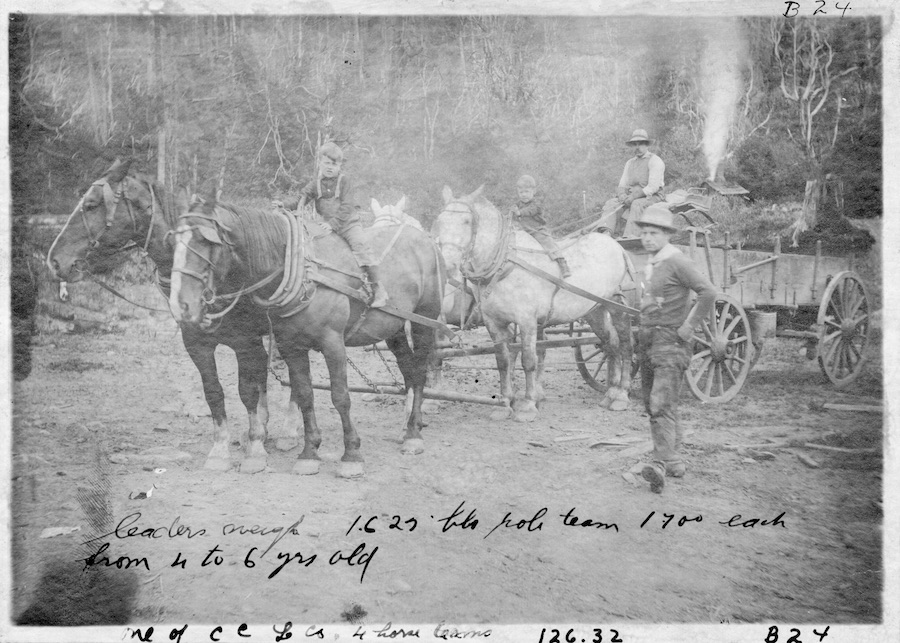

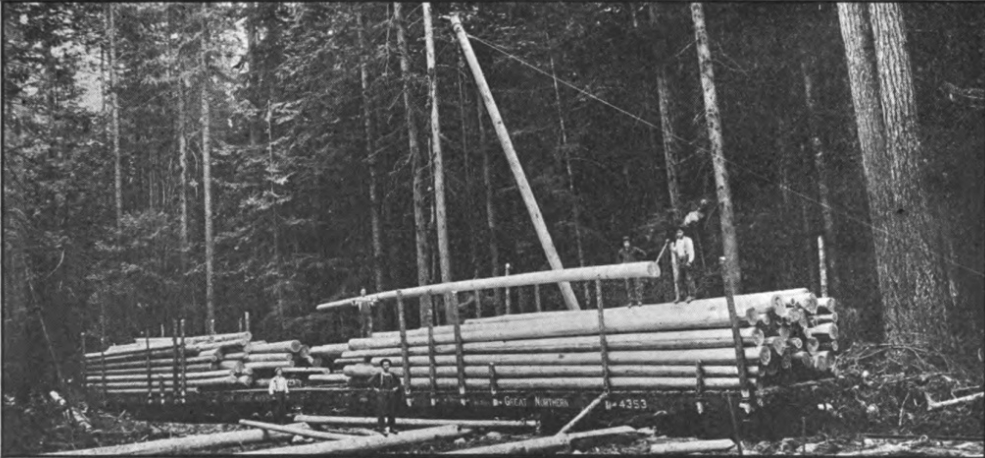

Let’s start at the beginning of pole production: logging. What did logging camps look like for workers in this era?

Much of the labor of producing utility poles was performed onsite at the logging camps where wood was felled by seasonal laborers. Here, labor was divided between a superintendent, foremen, teamsters, loaders, swampers, sawyers, office staff, timekeepers, and a cook. These were overwhelmingly male spaces, which makes the presence of children in this image intriguing; perhaps this image captures a rare family visit to a logging camp.

This image also shows that a lot of the human labor at logging camps was organized around the work of horses, who were used to haul cut logs to transportation points — either rivers, whose motive power was harnessed to float logs downstream at no cost, or train cars. Poles were then transported to pole yards, where much of the finishing work was done.

Historians of telecommunications have tended to focus on the desk work or customer-facing service work of telegraph operators and messengers, but my research instead foregrounds the labor of constructing and maintaining telegraph infrastructure. Behind every telegram delivered lay a history of strenuous, and often dangerous, human and animal labor.

Your research reveals how telegraphs were intimately related to the material world. What did it take to make telegraph poles from start to finish?

For the most part, the very first telegraph lines were built with wood taken from near the site of construction along the right of way. For many telegraph companies, it was more important in the immediate term to establish a right of way than it was to build a durable network. So telegraph construction crews simply chopped down and used whatever wood was available, even if this wood was not particularly fit for the purpose.

Over time, as networks expanded and as companies introduced pole specifications and standards, an entire industry emerged to supply utility companies with poles. The Western Union Telegraph Company, which was the largest telegraph corporation in the 19th century, operated its own pole yards in Michigan and Tennessee, but smaller-scale utility companies acquired their poles from independent suppliers. These suppliers purchased poles from logging companies and stockpiled them in pole yards. From there, they were transported to construction sites via railroads. But pole yards were more than just distribution points; they were also sites of labor, where the logs were finished by being stripped of their bark and cut to standard dimensions. Later, when utility companies began to demand their poles be preserved, chemical treatment facilities were installed at pole yards.

Where were the pole yards located, and how did they relate to railroad and other transportation networks?

Although historians have made much of the fact that the telegraph divorced communication from transportation, a focus on the pole supply shows that the telegraph relied on transportation networks. Some of the largest pole yards were located in Chicago and Michigan, at the meeting point of water and rail transportation routes. Poles were transported across the Great Lakes from logging camps to pole yards via rafts and steamships, and then from pole yards to construction sites via rail. In addition to this, Western Union had a large pole yard in Chattanooga, Tennessee, which was a distribution point for southern pine poles.

By concentrating on the physical infrastructure of telegraphs, my research demonstrates that electricity relied on steam; long-distance electrical communication was inconceivable without colossal amounts of organic materials like wood and coal.

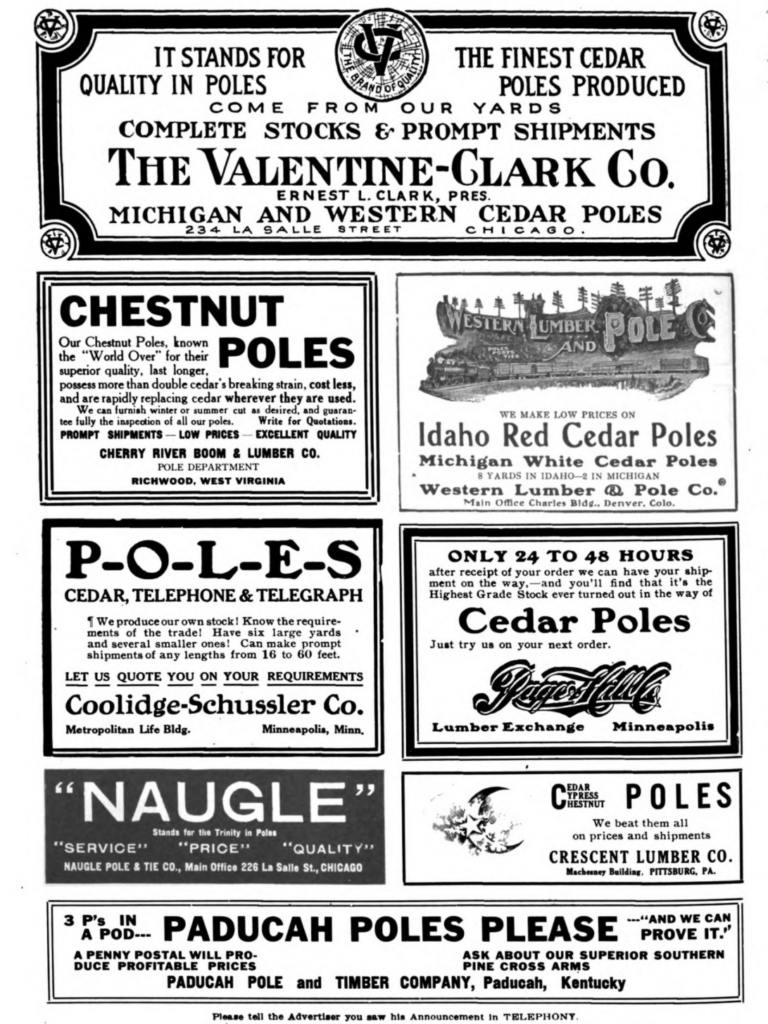

In these advertisements from Telephony, an industry trade magazine, we can see how pole producers promoted their poles. What kinds of trees were typically used for poles, and where did they come from?

The preferred species of wood for telegraph and telephone poles was cedar, because cedar is both durable and light, meaning it is relatively cheap to transport and handle. (The same quality that makes cedar suitable for telegraph poles — its lightness — is what made it attractive to woodpeckers; the softer the wood, the less energy has to be expended in excavating nest holes). Other favored species of wood included pine and chestnut, although chestnut blight wiped out much of the chestnut supply at the turn of the 20th century. In the West, douglas fir and western red cedar were widely used. Most of the poles used in the eastern United States came from Canada and the Upper Midwest — specifically, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. By the turn of the century, there was a burgeoning international trade in poles; poles were imported from Canada to the US and exported from the US to Egypt, Greece, Chile, and many other locations across the globe.

In this image, we can see the massive scale of telegraph and telephone pole production. What were the ecological impacts of these practices?

Telegraph and telephone line construction contributed to massive deforestation and habitat destruction, but this ecological impact was largely invisible to people who used the technology. After telegraph poles were stripped of bark, cut to standard dimensions, and spread out over great distances, they lost a lot of their apparent treeness. The location of logging camps and pole yards also meant that most of the environmental impacts of telegraph construction were geographically displaced; building a telegraph line in Arizona might mean cutting down thousands of trees in Wisconsin, for example.

Importantly, some of the environmental impacts of telegraph construction could have been mitigated had utility companies paid for their poles to be treated with preservatives. While expensive and time consuming, chemical treatment could extend the lifespan of a pole by many years, thus lessening the need for replacement poles. In the 1900s and 1910s, the U.S. Forest Service, driven by the conservation ideal, urged telegraph and telephone companies to treat their poles. But these efforts met with little success; it was simply more cost-effective, at least in the short term, for companies to replace poles than proactively to treat them. This began to change in the 1920s, when the increased cost of replacement poles started to reflect the dwindling supply of wood.

This photograph brings us back to the woodpeckers and their impact on the growing telecommunications industry. How do woodpeckers help us tell the history of telecommunications in a new way, and how have historians told the story of the telegraph?

In this image, we see animal traces (woodpecker holes) side-by-side with traces left by humans, who have carved their initials into the wood. This is a perfect metaphor for how the historical record contains both human and nonhuman traces, a concept beautifully explored by the historian Etienne Benson. For 19th-century Americans, telegraph poles may have represented the triumph of science and technology over nature, but for woodpeckers, they represented something far more prosaic: potential nesting sites. The image is also suggestive of how our physical surroundings, which both reflect and make possible commercial and economic life, are co-created by humans and nonhuman animals. Finally, woodpeckers remind us that the story of the telegraph is inescapably a story about wood. Rather than transcending the organic world, the telegraph was very much embedded in it.