How do we understand the barriers that women face in becoming political candidates? Melanie L. Phillips, who completed her PhD in the Charles and Louise Travers Political Science Department at Berkeley in 2022 and is currently a Lecturer in the Political Science Department and a Research and Evaluation Associate at School-to-School International, suggests that the problem is more complex than adding more women candidates or increasing the number of women in political power.

Phillips examines the biases of the “selectorate,” the party gatekeepers who pick each party’s candidate for the general election. Her research analyzes the gendered ways that candidates are judged based on such factors as their family and wealth. Her work shows how women’s political representation in African countries is shaped by the intersection between the rules governing candidate selection and the norms associated with gendered family roles.

For this Matrix Visual Interview, Julia Sizek, Matrix content curator and postdoctoral scholar, asked Phillips about her research, for which she used a novel dataset from the election process in Zambia between 2015-2019.

Your research on women’s access to political office focuses on Zambia. What are some of the key issues that you research, and why did you decide to focus your research on Zambia?

I decided to focus my research on women and their experience with candidate selection in Zambia because of an interview I had conducted during a prior research trip with Honorable Josephine Limata, a member of the Zambian Parliament.

In 2015, Limata managed to win the parliamentary seat in Luampa constituency, in Western Province, as an independent candidate — an incredibly difficult feat in Zambia, which has seen the dominance of a two-party majority system since the beginning of multi-party democracy in 1991. Despite clearly being a strong candidate who had the support of the voters, she was not selected as the candidate by either the Patriotic Front (PF), the incumbent party, or the United Party for National Development (UPND), the opposition party.

Her problem was Zambia’s candidate selection process. In order to become a candidate for Member of Parliament in Zambia, aspirants (individuals who want to become politicians) must be selected by a political party. This process of selection is called “candidate selection,” and the individuals in charge of evaluating the aspirants are the “selectorate.”

When asked about the puzzle between her clear electability and both PF’s and UPND’s decision not to support her candidacy, she stated that “the majority of political parties don’t adopt [select] women. We are undermined by men…. There are plenty of women who stand, but, the way they are chosen, men are the majority who get adopted [selected].”

Women in Zambia face an array of barriers when attempting to stand for political office, such as gender-based gaps in financial resources, education, household responsibilities, and autonomy. The barrier highlighted most often is financial resources (or lack thereof). Financial resources are key to any successful election campaign, especially in developing countries, and are necessary to mobilize political support. Candidates must often finance and orchestrate their campaigns, and have to mobilize massive amounts of personal support and financial resources to hold popular rallies and travel across the electoral district where they are campaigning. As scholar Dominika Koter showed through her research in in Benin, elections are incredibly expensive due in large part to voters’ expectations that candidates will provide goods such as food, petrol, or cash during their campaign — and Eric Kramon’s research in Kenya from 2016 highlighted how political parties seldom cover the costs of political campaigns.

My research, however, adds nuance to understanding these barriers. I contend that to truly understand the gendered nature in which party gatekeepers scrutinize women, and how women’s treatment differs from that of men, we must consider how the family unit shapes women’s lives differently in Zambia and around the world. One of the most notable benefits of political families is the collection of resources across generations, as studied by Gary Solon (1992), but women do not benefit equally due to inequalities in inheritance laws and social norms. In my research, I analyze how the perception of access to resources is a major factor in party gatekeepers’ decisions. Women and their ability to compete in elections are heavily moderated by the support and resources of their families.

Drawing on a survey experiment with 1,339 party gatekeepers in Zambia, I show that family backgrounds are one of the strongest predictors of candidate selection for both men and women; they are also the most gendered. I find that women are differentially evaluated. Men are rewarded during candidate selection for being the heads of traditional households. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to be rewarded when their families have histories of demonstrated partisan loyalty, which refers to the level of dedication and loyalty an individual has to a particular political party. I also show that the gender of party selectorates does not substantively change how candidates are evaluated: women selectorates show no gender preference for women aspirants, and like men, punish women candidates who deviate from cultural expectations. However, I demonstrate that an individual selectorate’s level of sexist beliefs does condition how they view more masculine candidate attributes. Selectorates with higher levels of sexism favor men and those with lower levels favor women. Contrary to expectation, women selectorates have higher levels than men of ambivalent sexism, which is a measure that includes both hostile and benevolent forms of sexism.

How did you measure how selectorates examine potential candidates for office? What were your research methods, and what did you do during your fieldwork?

My dissertation is rooted in a mixed-methods approach that combines extensive qualitative fieldwork with survey and experimental techniques. Methodologically, it presents a valuable contribution of new data sources. These include candidate recommendation reports written during candidate selection; survey experiments conducted with over 1,300 party members across Zambia; and qualitative evidence from over 90 interviews with candidates, party members, members of parliament, and women’s groups in Zambia. I collected this data in Zambia between 2015 and 2019.

One of the key contributions of this research is the unique sample I leverage in order to understand the recommendations of gatekeepers, based on the in-person survey I conducted with 1,339 party gatekeepers in both the PF and UPND. Experimentally, the survey used a vignette design, which presents a description of a candidate profile with randomized changes to the description. Each participant was given a randomized profile of a hypothetical candidate that included their name, gender, family status, financial capacity, party endorsement, and organizational capacity (defined as their ability to mobilize and the strength of their networks). These hypothetical candidate recommendations were based on actual recommendations that I had collected during my field work. Participants of the survey were very familiar with this task, as each level of the party structure writes and submits these kinds of recommendations to the province and the national executive committee after interviewing candidates during the candidate selection period.

Following the vignette experiment, the surveys asked participants a range of questions to gauge their political experience, candidate preferences, measures of ambivalent sexism, and financial expectations during the multiple phases of candidate selection.

One of your key arguments hinges on the idea that a woman candidate will be judged based on her role in her family, and that the relationship between her family and the political party that she hopes to represent can also determine whether she’ll be selected. What are some of the aspects of family life that are relevant to party selectorates?

As Diana O’Brien showed in her research looking at political systems across 11 different countries, political parties are typically built through networks dominated by men that are unreceptive to outsiders — in this case, women who are not connected to those networks. As a result, as Olle Folke et al have showed, women often need to leverage their families’ political connections to get the name recognition, support, and resources necessary to compete electorally. This is especially the case in countries where citizens prioritize traditional family roles, as illustrated by the research of Alexander Baturo and co-authors. Meanwhile, work from Linda Richter has demonstrated that women who do have politically relevant family connections are more likely to access political positions and opportunities that are closed off to the majority of women.

Parties and the selectorate also use those familial ties as a heuristic for a candidate’s qualifications. Political families provide access to formal and informal advantages such as financial and educational resources or personal connections and positive reputations. And as Timothy Besley and co-authors have shown, party gatekeepers infer the qualities of a candidate based on the success of their family as a whole, assuming that qualifications like resources, education, and training will be similar among those within the family. Olle Folke’s work has demonstrated how these family connections matter more to women, who are at an inherent disadvantage, and show that women can make up for gender-based disadvantages by having dynastic family ties during candidate selection.

In my research, I explain how the family attributes of candidates shape how the selectorate perceives their strengths and weaknesses. To study gendered effects in candidate selection.I specifically distinguish between a family status mechanism (for which I use marital status as a proxy) and a loyalty mechanism, a measure of a candidate’s family political ties.

Family status, or more broadly the composition of one’s family situation, plays a significant role in how political party members evaluate candidates. Through my analysis of the marital status of candidates, I found that members of the selectorate hold a double standard when evaluating candidates based on their family structure. Whereas men benefit from certain family dynamics (for example, when looking at pay gaps, married men are typically paid the most), women are punished for deviating from traditional expectations. Similar mechanisms have been documented by Amanda Clayton and co-authors based on research they conducted in Malawi. This double standard, I argue, is consequential in candidate evaluations. I expect that women are less likely to be rewarded for conforming to normative family expectations than men, while also being penalized more harshly for deviating from them.

I found a contrasting result when studying the loyalty mechanism, which measures a family’s history of political commitments. Women benefit from a form of benign chauvinism that depicts them as more loyal and devoted than men. Women are perceived to be more loyal, and scholars Zetterberg (2021) and Thames and Rybalko (2010) have found that women are more likely to remain loyal within pre-established family networks, such as those based on political partisanship. This expectation leads party members to believe that women will be less likely than men to defect from their political party. In this respect, party gatekeepers are more likely to reward women for having a family history of partisan loyalty.

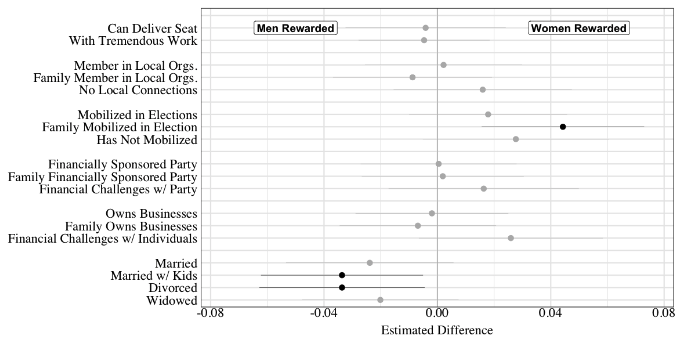

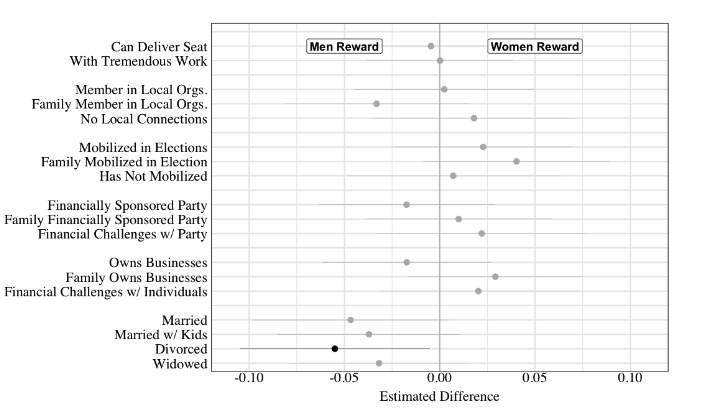

Walk us through the results highlighted in Figure 2 (below). What does this reveal about the different ways that men and women are judged by party selectorates?

Core to my work is the claim that men and women are evaluated differently for the same family-based attributes. Following the analytical approach seen in Teele et al. 2017 and Clayton et al. 2019, I calculate the gender gap: the difference between the treatment of men and women, controlling for other remaining attributes, such as income and experience in politics. Positive coefficients show that an attribute has a gender gap in favor of women, and negative coefficients show a gender gap that favors men.

The results presented in this figure support my claim that party selectorates reward women candidates more than men for familial political loyalty. While both men and women are rewarded for individual invested loyalty, women receive a 4% bonus compared to men for having a family that is loyal and that has previously mobilized in elections, for example through campaigning, holding rallies, or donating.

The results show that party selectorates reward men for demonstrating traditional family status while punishing women who deviate from the norm. Selectorates disproportionately reward men for being married with two kids, which results in a 3% bonus for candidates who are men compared to women. Additionally, women are penalized severely for being divorced, which results in a 4% bonus for men.

While this study finds notable gendered effects, it also highlights some null effects where we might expect to find gendered differences. For example, while men are often more likely to be political brokers and dominate local traditional authorities, the selectorate rewards men and women equally for having local connections.

Individual and family financial attributes also appear to have no gendered effects: they increase and decrease both men’s and women’s evaluations indistinguishably. Still, even though I found a null effect here, women face greater obstacles in obtaining financial independence and/or success in many countries. In research from 2008, Doss,Grown, and Deere showed that women in Latin America and Africa have significantly less access to and ownership of land than do men, and women are also less likely to own or inherit productive forms of livestock. Inequalities in access to financial resources are clear across Zambia. Women and men across numerous interviews highlighted that the role of head of household, and the control of family resources, was specifically restricted to men. So even though women and men may be judged similarly for comparable financial resources, it is often more difficult for women to obtain them.

What needs to be considered here is that the attributes selectorates do evaluate differently for men and women tend to develop or change. One’s family and political history are not an individual choice, nor can a political history be established quickly if an individual decides to enter politics. Therefore, women candidates, regardless of whether they recognize that they have a political advantage, are limited in their ability to act on it: it simply exists as an attribute that is evaluated when they seek office. Further, in new democracies where traditional norms prevail in an individual’s family dynamic, and whether they remain “not divorced,” is often out of a woman’s control. What this tells us is that the number of women in office will not change by focusing on candidate training and increasing the supply of women candidates alone. We must also look toward training the selectorate to eliminate the gendered differences in evaluation practices.

The gender makeup of a selecting committee is often used as a proxy for the committee’s willingness to select a woman candidate. However, in your research, you find that this is not a good means to predict whether a committee will select a woman candidate. What did you find?

Many scholars have suggested that the key to decreasing bias against women during the candidate selection process is to include women in party leadership. But I found that women are not immune from gendered biases. My research finds that an individual’s level of internalized sexist beliefs, measured through ambivalent sexism, determines how gatekeepers evaluate gendered attributes.

To investigate this, I used a modified version of the ambivalent sexism index, which (as described by Peter Glick and Susan T. Fisk) “measures hostile sexism (HS), sexist antipathy toward women, and benevolent sexism (BS), subjectively favorable, yet patronizing, beliefs about women.” I found that an individual’s level of sexist beliefs conditions how they view candidate attributes such as financial resources. Party gatekeepers with higher levels of ambivalent sexism reward men for gendered attributes, whereas those with lower levels reward women.

Advocates often recommend that more women should be included in decision-making bodies, arguing that this would decrease biases against women candidates. However, my study suggests that adding more women is not enough: women are not immune to gender biases and have their own embedded biases. Women gatekeepers punish women candidates more severely, and do not appear to reward women for demonstrating family political loyalty. Furthermore, when looking at the degree to which individuals hold sexist beliefs, I find that women score significantly higher on the ambivalent sexism measure than men in the sample. Therefore, the solution to decreasing biases against women may not be as simple as increasing the number of women on selection committees. Instead, we should train gatekeepers on unbiased evaluation techniques and strategies to root out implicit gender biases that ultimately affect the institutionalization of democracies around the world.

How might these findings about the role of the family in candidate selection be applied to other contexts, for example, in considering local or municipal elections elsewhere in Africa or in places like the United States?

While the theory presented in my dissertation is rooted in qualitative fieldwork and tested empirically with data from Zambia, the argument is broadly generalizable. It is not necessarily that the findings discussed in this dissertation are unique to Africa or even to newer democracies. However, the strength of these effects is likely moderated by a country’s level of political institutionalization, the strength of their traditional gender norms, and the level of inclusivity and transparency in their candidate selection mechanisms.

The effects outlined in my work are likely stronger in areas with weaker levels of political institutionalization, where rules, processes, and expectations governing political bodies both formally and informally have not been established. Women, in these contexts, must engage with a higher degree of uncertainty when entering the nomination stage. Additionally, the lack of transparency that often comes with lower levels of political institutionalization likely makes room for gender to have a larger effect on evaluation and selection decisions.

Women in electoral democracies throughout the world must compete within societies that have strict gender roles that establish gender norms and expectations. In turn, these norms and expectations influence how party gatekeepers measure a woman’s political qualifications and competitiveness. Additionally, in some form, gender-based socioeconomic inequalities exist in all electoral democracies. These disparities make women’s ability to meet the qualifications necessary to compete for political office more difficult. Moreover, in countries where gender schema and people’s expected adherence to them are stronger, women are more likely to face barriers in evaluations when vying for political office.

Lastly, in countries where voters are directly in control of candidate selection through primaries, the role of party gatekeepers will be diminished. Nevertheless, voters will continue to evaluate women within and against these gendered expectations, and political parties will still play a role in how candidates navigate this reality.