The pandemic and the war in Ukraine have reshaped global geopolitics, trade, and security. How will these changes affect the relationship between the US and China, Europe, and the Global South? How will they impact US firms operating globally, and how might foreign leaders — and notably the Chinese leadership — respond?

Recorded on February 16, 2023, this panel discussion featured a group of distinguished scholars addressing these questions, and the possible implications for the global multilateral order established in the second half of the 20th century. The panel was held in Spieker Forum at the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, and was co-sponsored by Social Science Matrix and the Clausen Center for International Business & Policy.

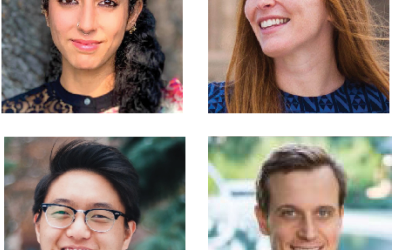

Panelists

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar is the tenth president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. A former justice of the Supreme Court of California, Justice Cuéllar served two U.S. presidents at the White House and in federal agencies, and was a faculty member at Stanford University for two decades. Before serving on California’s highest court, Justice Cuéllar was the Stanley Morrison Professor of Law, Professor (by courtesy) of Political Science, and director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford. In this capacity, he oversaw programs on international security, governance and development, global health, cyber policy, migration, and climate change and food security. Previously, he co-directed the Institute’s Center for International Security and Cooperation and led its Honors Program in International Security.

James Fearon is Theodore and Frances Geballe Professor in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, a professor of Political Science, and Senior Fellow in the Freeman-Spogli Institute for International Studies. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences (elected 2012) and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (elected 2002). Fearon’s research interests include civil and interstate war, ethnic conflict, the politics of economic development, and democratic accountability.

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas is the Economic Counsellor and the Director of Research of the International Monetary Fund. He is on leave from UC Berkeley, where he is the S.K. and Angela Chan Professor of Global Management in the Department of Economics and at the Haas School of Business and Director, Clausen Center for International Business and Policy. Professor Gourinchas was the editor-in-chief of the IMF Economic Review from its creation in 2009 to 2016, the managing editor of the Journal of International Economics between 2017 and 2019, and a co-editor of the American Economic Review between 2019 and 2022. He is on-leave from the National Bureau of Economic Research, where he was director of the International Finance and Macroeconomics program, a Research Fellow with the Center for Economic Policy Research CEPR (London) and a Fellow of the Econometric Society.

Laura Tyson is Class of 1939 Professor of Economics and Business Administration and Distinguished Professor Emerita of Economics at UC Berkeley. She is an influential scholar of economics and public policy and an expert on trade and competitiveness who has also served as a presidential adviser. She also chairs the Board of Trustees at UC Berkeley’s Blum Center for Developing Economies, which aims to develop solutions to global poverty. She is the former Faculty Director of the Berkeley Haas Institute for Business and Social Impact, which she launched in 2013. She served as Interim Dean of the Haas School from July to December 2018, and served previously as dean from 1998 to 2001.

John Zysman (moderator) is Professor Emeritus at UC Berkeley and co-founder/co-director of the Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy. He received his B.A at Harvard and his Ph.D. at MIT. Zysman’s ongoing work covers the implications of platforms and intelligent tools for work, entrepreneurship, and international competition; and the economic challenges and opportunities of climate change and the green economy. From these positions, Zysman has made contributions to the policy and intellectual debates, building a record of thought leadership on the global economy going back five decades.

Listen to the panel as a podcast below or on Google Podcasts or Apple Podcasts.

Transcript

Economics and Geopolitics in US International Relations: China, Europe, and the Global South

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[MATILDE BOMBARDINI] Good morning, everybody, or good afternoon. Welcome, everyone. My name is Matilde Bombardini. And I am an associate professor in the Business and Public Policy Group here at Haas. And together with Professor Maurice Obstfeld, I’m co-director of the Clausen Center for International Business and Policy. I should say caretaker, co-director. The Clausen Center together with the Social Science Matrix led by Director Professor Marion Fourcade, who is here, are happy to present our distinguished panelists.

So we have John Zysman, who is the moderator. He’s a professor emeritus at UC Berkeley and co-founder, co-director of the Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy. Through his many contributions to policy and intellectual debates, John has built a record of thought leadership on the global economy going back five decades.

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas is the Economic Counselor and the Director of Research of the International Monetary Fund. He is on leave from UC Berkeley, where he is the SK and Angela Chan professor of Global Management in the Department of Economics and at Haas, and Director of Clausen Center for International Business and Policy.

James Fearon is the Theodore and Frances Geballe professor in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and a professor of political science, a senior fellow in the Freeman-Spogli Institute for International Studies. He’s a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Mariano-Florentino Tino Cuellar is the 10th president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a former justice of the Supreme Court of California. Justice Cuellar served two US presidents at the White House and in federal agencies and was a faculty member at Stanford University for two decades. Before serving on California’s highest court, Justice Cuellar was the Stanley Morrison professor of law, professor by courtesy of political science, and director of the Freeman-Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University.

Laura Tyson is class of 1939 professor of economics and business administration and distinguished Professor Emerita of economics at UC Berkeley. Professor Tyson is well-known for his distinguished career in both academia and government services. She is a former National Economic Council advisor and past Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors. So join me in welcoming our speakers.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Before turning us over to Pierre for the first round of this, I’m going to do a brief overview of what we’re going to be talking about. The title of the session, in fact, suggests quite clearly the themes. These are volatile and uncertain times. And our effort is to try and get to come to grips with them in one way or another.

Each panelist will take seven or eight minutes maybe, give or take a little more, you never know, and lay out their basic views on this. Then we’ll do a second round in which they can have interchange with themselves or add to questions, or I may provoke some of them to some extent. And then we’ll open it to questions and answers to the group as a whole.

Pierre will, in fact, be addressing, as he begins, the extent of geoeconomic fragmentation in the scenarios that may emerge. Then James Fearon, who brings a security lens to these questions, will focus considerably on the China challenges that are before us. Tino Cuellar will, I’m hoping, be able to show us how we can reconcile these differing imperatives of security and economy, particularly in the context of climate. He’s saying he can’t, but we know that he can. But we’ll benefit from his insights. And Laura Tyson will, with a particular focus on climate, will, as she always does, provide an integrated and insightful interpretation of developments.

With that, I’m going to turn to Pierre and say, from your work at the IMF, I’m hoping you’ll give us a sense of the extent of trade and financial fragmentation and the scenarios, as I say, that might emerge. As we move into a discussion, we will all want to consider that if the multilateral consensus that has been in the past is no longer possible, what approaches actually are in order? So Pierre.

[PIERRE OLIVIER GOURINCHAS] Thank you. Thank you, Chris. Well, thank you all very much for being here. I will use the seven minutes or so I was instructed to use in the first round to talk about geoeconomic fragmentation and the implications for the global economy. And this is, as you can imagine, a topic that we spend quite a bit of time thinking about at the Fund in the research department and also in other areas of the Fund.

So I would start by offering some comments on the extent of geoeconomic fragmentation that we can see already in the global economy. And then I will discuss some more speculative assessment of some scenarios that we have been working with to try to assess what might be happening if things really start unraveling.

So first, I will start by showing you some signs of geoeconomic fragmentation, what we are seeing already. And here, when I talk about geoeconomic fragmentation, I want to focus on a fragmentation that is policy-driven and might be policy-driven because of national security considerations. It might be having to do with sovereignty or autonomy. But I don’t want to have in mind something that would be due to some change in the environment or some global precautionary measures that countries would be taking.

For instance, you might imagine that all we’ve seen in the aftermath of the global financial crisis that there were some measures, some macro financial measures, prudential measures that were put in place that reduced some of the cross-country exposure. But they were designed to make the system more resilient. And I wouldn’t want to consider that as part of what we’re discussing today.

So I’m showing you here on this figure two different indicators that we are starting to look at, we’re following. So first, on the left, you can see mentions of national security in our annual IMF– annual report on the exchange arrangements and exchange restrictions. And you can see that after 2015, this starts picking up. This is sort of very low and not very relevant, it starts picking up in these reports in terms of some of the motivations for some of the exchange rate arrangements that countries are taking. And even net of Ukraine, this is still going up. So it’s one first indicator here.

Another indicator is the one on the right, which is coming from data from earnings calls. And you can see there a rapid increase. That starts actually before 2022, but a rapid increase in the mentions of themes like reshoring, onshoring, friendshoring, near-shoring in these earning calls. And of course, some of it starts during the COVID crisis, because, at that time, there’s already a concern about the vulnerabilities in the global supply chains. But this is exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Now, when we’re thinking about global economic, geoeconomic fragmentation, of course, we can think about a number of channels through which this might affect the global economy. So you might think that this will reduce trade. And to the extent, that trade has been one of the vectors through which countries have been able to grow faster. And there’s a lot of evidence of that or people have been able to be pulled out of poverty, or levels of food insecurity have been decreasing over time. Then something that would basically revert the extent of globalization we’ve seen and reduced trade might actually have adverse effects on the economy.

You might also think about technology diffusion as being affected by geoeconomic fragmentation. I have something to say about that in a minute. I mean, ultimately, technology and productivity growth is the key driver of improvements in standards of living. And so if we have geoeconomic fragmentation, we could also have a growing gap in terms of levels of technological development between different parts of the world. And that means that the parts of the world with the lower levels of technology would be suffering in terms of their improvements in standards of living. That would also affect competition. That would affect the rate of innovation. So it could affect both the gap between countries but also the level at which innovation grows overall.

But there are other channels that we can think about that might be relevant when we’re thinking about geoeconomic fragmentation. So you might think about increased barriers to migration. And that would reduce efficiency. That would hinder also innovation and technological diffusion. That would worsen adverse demographic trends that we’re seeing in different parts of the world. And that could also raise international tensions. We could have a fragmentation in capital flows. That would also have an impact by, for instance, limiting the amount of remittances streams that is very relevant for some low-income countries or limiting financing choices.

You could think that it could also increase uncertainty. A world in which you have this policy decision visions is a world in which policy uncertainty is increasing. And there’s a lot of evidence indicating that policy uncertainty is actually hurting investment. It’s leading to suboptimal decisions. It’s leading to delays. It’s increasing precautionary savings, for instance. And all of that could weigh down on economic activity, not to mention the fact that in a volatile and uncertain environment, you have more room for policy mistakes.

And finally, you could imagine that geoeconomic fragmentation would be something that makes it harder to coordinate on global public goods, make it harder for countries to agree on some of the key aspects that they need to work together on, whether it’s climate and the ability to implement measures that would allow us to stay below 1.5 Celsius in terms of temperature increases, or future work on health preparedness, pandemic mitigation, or the ability to deal with a large number of countries facing debt problems, for instance.

So what I’m going to show you is I’m going to show you some estimates where we try to work out what these scenarios would imply for the global economy and for different regions. So here, what I’m showing you on this figure here is based on some analysis we’ve done in a house at the Fund, where we’re looking at a situation where we’re splitting. And of course, we have to make some assumptions. And so we’re splitting the world into two blocks. And we’re using the March 2, 2022 United Nations General Assembly motion to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to sort the countries in the different groups– the countries that voted to condemn and the countries that didn’t vote to condemn.

And then we imagine that, as a result of this fragmentation, you would have in green, what I’m showing you is what happens if you have sanctions or if you stop trade on energy and high tech, so what we call energy and high-tech decoupling. And then in red, we add to that non-trade barriers that would basically go back to a level of trade between the different blocs that would be similar to what we had in the Cold War between the West and between the Soviet Union.

And the cost are significant for the world. There are about 1.5%. A lot of it is actually coming from the trade, the energy and high-tech decoupling. There can be much higher for some regions in the world. So the Asian countries, not surprisingly, are very, very vulnerable to a decoupling of the global economy, a fragmentation of the global economy. And you can see that for them, the estimated cost would be on the order of 3%, so about twice as large.

Not surprisingly again, but when you plot the costs or the welfare losses or GDP losses against the degree of openness, you find a very strong relationship here. Small and open economies are much more vulnerable. And that’s something that characterizes a lot of emerging market and developing economies.

Now, that’s one scenario where we have this sort of energy and high-tech decoupling. But there are a bunch of other scenarios we’ve run or other researchers have been working on the WTO or elsewhere. And so here, in a recent staff discussion note that we published in mid-January, we surveyed the landscape, if you want, and we put together this figure that shows the range of estimates.

So this is a pretty large range. And it goes from something like 1.5% of GDP, as I’ve already mentioned, to something that is on the order of 7% to, for some individual countries, up to 10%, 12%. And it really depends on how deep the fragmentation scenario is if you assume that there is really no trade at all between the different regions here. Whether you have a technological decoupling or not, that matters a lot for the long-term losses. Whether you have any substitution in the short term, so that depends on what the elasticity of substitution in this modeling exercise.

And in the sense, you have in a U-shape relationship. In the short run, it’s very hard to substitute a way, so it might be very costly. Or let me restate, if it is very hard to substitute a way, it could be very costly. In the long run, you may have substituted a way, but then the technological decoupling might kick in. And so you may have high losses because you’re sort of on this different productivity growth path. And so you might have also long and elevated costs.

We find that overall emerging markets and low-income countries are the most vulnerable. And in part, because they are behind the technological frontier. And any fragmentation would make it much, much harder for them to catch up. And they’re also quite open to start with.

Now, what does this imply for policy challenges? And this is my next to last slide. So there’s been a lot of– as I’ve mentioned, there’s been a lot of discussion about reshoring. Some of the measures that have been implemented by some countries, in particular in the US, have made it a condition for being eligible for subsidies and things like that.

And one of the point that we make is that we have to be careful is if the risk is the concentration risk that, your supply chain may be very concentrated, for instance, in semiconductors that are made in Taiwan in only one plant or one factory in Taiwan, then reshoring does not necessarily reduce concentration risk. In fact, the way that trade matrix is organized already, we have a fair amount of what you might call want-to-go-home bias. And this is what this figure on the left is showing.

If you look at the domestic share of intermediates, that’s the blue bars, it’s much higher than the domestic share in production. So in other words, this is an extent to which countries are already producing a lot of their domestic intermediates as opposed to procuring them from somewhere else in the world. And so reshoring would actually aggravate this pattern.

And in a little experiment we run, that’s the figure on the right, we ask, well, what would happen if you have a shock that is similar to about a 25% contraction in labor supply in a major intermediate goods supplier comparable to China? So think of this as a pandemic that would hit a country like China. And because of the centrality of China in the number of trade relations, it, of course, has a large impact on the world economy. So we estimate, on left bar, we estimate that the cost is about 0.65% or actually the world is a little bit more than that. It’s 0.8. It’s not it’s not on this figure.

But then if you diversify your supply chains, not concentrate them, diversify THEM then you get the black squares there. So you can reduce the impact and the dependency on any one single large supplier by a lot. So the point here is that diversification of global supply chains is much more important in terms of building resilience and then reconcentration.

Now, I will end with this final slide here that is coming back to what I started with, which is evidence of geoeconomic fragmentation, but looking at it from a different perspective by looking at it from the current account balances. So the difference between savings and investment or domestic absorption and production.

And here, what you have on the left is what we call a global imbalances graph. So you have the different countries or regions of the world above zero or surplus countries or regions below 0 or deficit countries or regions, starting in 1990 to 2022. And something interesting is happening when you’re looking at this imbalances. First, you see that they are sort of growing again of late. And that, meaning that the dispersion, the surpluses, and the deficits are increasing again. And this is in large part reflecting the energy shock that the global economy suffered last year.

And so what that tells you also is that a lot of these surpluses are located in countries that are actually on the other side of the countries running the deficits. You have an increase in the deficits of the US, for instance. And you have an increase in the surplus of countries like China or Russia, Saudi Arabia, which are not necessarily countries that you would associate with countries being in the same geopolitical camp. So for all the evidence of geoeconomic fragmentation and the trade fragmentation, et cetera, the financial flows are telling you there is still a lot going on. There’s a lot of interdependence there. And it’s a point that you want to keep in mind.

But what has changed perhaps already, and we’re seeing that on the right, is the composition of this flows. So what this here I’m showing you on the right is the outflows and inflows for three countries together– China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. And notice that in the past, the black component was quite irrelevant. And that’s the effects reserves. And so there was quite a bit of reserve accumulation when these countries were running surpluses.

And this has disappeared in recent years. And what you see instead is an increase in other types of flows or errors and omissions, which means things that we can’t quite categorize. And we don’t really know where they’re going or what’s happening to them. So what this is suggesting is that there is an increased opacity in financial flows in recent years.

Now, you can imagine that this is an increased opacity, because the number of countries that are running surpluses may not want to accumulate reserves in the form of US treasuries in an environment where US treasuries might be frozen for instance as has been the case with central bank of Russia. So here, we have a displacement in terms of the composition of these flows, not necessarily a change in terms of the magnitudes of the overall balances, but certainly a lot less transparency and a lot more opacity going forward.

And I will end with this final point, which is that in the world we’re in, we used to think about the need for countries to maybe run current account surpluses, maybe for mercantilist reasons, that’s an argument that’s sometimes advanced, or maybe for the cautionary reasons precisely to build these reserves that they can then use to buffer against shocks. And in a sense, this second motive may be strengthened by the environment in which we live. The experience of what happened to Russia in 2022 illustrates how it’s difficult for sanctions to bring a surplus countries to a standstill. And so that might actually give an additional impetus to countries trying to be in a current account surplus position. I will stop here. [APPLAUSE]

[JOHN ZYSMAN] James– while they’re moving the chairs around, we can get organized. James spent a year at the Department of Defense, where he contributed to the National Defense Strategy document that came out in October. So part of the question that he’s going to address is, how if the priorities then the defense priorities actually changed in recent years, to what do we attribute those changes? And I would add, to what extent does that become entangled with economics? But that we will set aside unless he wants to address it himself. So when we’re all set, I suggest the rest of us ascend. And James–

[JAMES FEARON] Should I go up here?

[JOHN ZYSMAN]Yeah. Why not?

We have some sort of order. I think you’re–

[INDITINCT CHATTER]

I’m going to come here until somebody moves me. It’s good.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] It’s good. We’ll get that now. Before James gets started, I would say Laura and I have back problems. So occasionally, we may stand up. That’s not because we’re going to walk out on everybody else but just try to stretch a little bit. So forgive us in advance.

[JAMES FEARON] Thanks very much. And thanks for the opportunity to talk here. I should start out. Yes, John mentioned I worked last year. I was leave from Stanford and spent it fascinating year in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, working with the group that worked on the 2022 National Defense Strategy. That said, this should go without saying, but just to be 100% clear, I’m talking as in absolutely no representation or on behalf of I’m talking DOD or the US government, but as a person from Stanford.

So also, I should say, I’m not an economist. And I can really– I’m better positioned to address defense and security challenges. I look forward to trying to do some integration in the conversation we have and in answering questions.

In terms of the broad questions John raised, what’s, I think, really striking is that the US National Security community, the defense policy world has been, for a couple of years now and very much in the last year or two, preoccupied with the possibility that the PRC will, at some point, in some unclear timeline, could be next few years, next decade, could be longer than that, use force to try to change the status quo on Taiwan.

You may or may not have tracked that there’s just in every couple of weeks, there are some new set of speculation, an argument someone says something about when they think this might happen. There’s a lot of focus on timelines. And I’d be happy to address that more specifically. But I mean, no one really knows, of course, as US senior leaders generally say or pretty much always say.

But you can also say that this preoccupation, I’d say, it’s based on a quite plausible view that there is a non-trivial risk that you could see military action of some form, by the PRC, to try to reincorporate Taiwan to change the status quo using force. And that there is a non-trivial risk that could lead to a quite major war, really major war, between the US and the PRC, or US allies and partners and the PRC.

That would be a disaster. It would be terribly costly in many ways, including it would be economically or it could be economically catastrophic, both in the region and globally. So I mean, I think this would be an interesting thing to discuss. But the degree of global economic fragmentation that might follow, I think, Pierre would almost surely agree, that the degree of fragmentation that could follow from such a conflict would make the kind of changes that we’re seeing in the absence of that look pretty marginal, I suspect, quite marginal.

Yeah. I’d be interested in– I mean, I think in some of your just thinking about some of the slides you presented, I’ll throw this out as something that would be interesting to discuss. I don’t think it’s really that plausible that we’d see decoupling or fragmentation on the order of what we saw in the Cold War. I think we’ll far more likely to see a much more marginal than that the current international economic system. Even in the absence of the use and smooth functioning of the multilateral trade institutions as occurred in the past, even without that, the built-in forces in global value chains and FDI and multinationals and lobbies in many countries for maintaining trade relations are pretty strong. But not my area.

So, of course, we hope that a major conflict, military conflict is a very– I think, it is a low probability event. A lot of the stuff that the 2022 NDS is focused on, and a lot of US Defense policy thinking these days is focused on what needs to happen to keep it this a very low probability. In a slightly longer term, a slightly longer run perspective, the US Defense policy is in the process of attempting to make a hard turn away from what had been core focus for much of the last 20 years, which was counterinsurgency and counterterrorism. And In the last 10 years– well, and more than that– the war in Afghanistan.

You see this concerted effort to try to shift towards a set of challenges related to the very large scale and very focused military modernisation of the PRC and a set of plausibly interpreted policy changes in foreign policy of the PRC that are raising concerns about, for example, the independence of– well, or the continued status quo on Taiwan.

So the focus of the 2022 NDS was– kind of a top line objective was this need to, as it says, sustain and strengthen deterrence on a set of vital national interests. And these are not exclusively but mainly major concerns related to major power conflicts. Taiwan being one such scenario but not the only one. Russia was characterized in the document as an acute challenge. And as we’re seeing, that’s also another major power issue very much, very obviously in play.

So how do economic considerations play into these defense priorities and objectives? My impression is that by the Biden administration and also previous administrations are– the general worry, like the motivation for these security policies or defense policies and orientation is a worry about an economic threats in the long run, medium and long-run threats to the political and economic autonomy of major trading partners in the Pacific Rim.

So the long-run concern would be, in the sense, that PRC policies may threaten US or could threaten US ability to trade and interact with major Pacific Rim economies, that PRC economic and military leverage may be increasingly used to influence their domestic politics, for example, essentially, to make the world safe for the CCP, as they see things.

So the response to this as well having been focused on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency since at least since 9/11, a whole bunch of things have kind of– there’s a lot of catching up to do in terms of reinforcing, enhancing deterrence for a different set of security or military problems, particularly in the Pacific. Doing so is in itself risky and tricky. I think there’s a good deal of attention to the risk of what in the field of international relations, we talk about, is called spiral dynamics. That the US in attempting to do things to enhance deterrence would actually increase the likelihood of conflict by increasing, say, PRC perception of threat or changing military balance or things like that. So it’s a tricky thing.

I think at the same time, coming back to economics a little bit, my sense is that, at least the Biden administration leadership understands that the situation is very, very different from the Cold War conflict with the USSR. And it’s different in many ways, but it’s particularly different in terms of the economic situation or the economic relationships.

And I think that, I guess, I get the impression reading the news and public discussions that a number of the administration’s actions have been interpreted– have been are sometimes interpreted as, oh, this is a kind of Cold War kind of response. And we’re talking about decoupling and fragmentation. And I can understand why those– why one might think that.

But I think if you look closely at Biden administration foreign economic policy documents and leadership statements, or, for example, the National Security Strategy, the overarching security document that comes out of the National Security Council is not specifically or exclusively defense-related, you see, I think, a quite clear understanding that countries in the region do not want to be made to choose between the US and the PRC. And that at the same time, it’s also inevitable and not even necessarily a bad thing that countries in the region and the US will be trading a great deal with China.

Just two days ago, I listened to a Deputy Secretary Wendy Sherman gave a talk at Brookings, where she made– asked these kind of questions, made these kind of points. And noting in addition that it’s not just countries in the region, but there’s a huge amount of Chinese investment in the US economy. She flagged that a prosperous Chinese middle class is in fact a good thing for US workers and for the US economy overall. So I don’t get the sense that there is a concerted– any concerted policy of economic decoupling or a notion of like, it would be a good thing to try to create economic blocs along the lines of the Cold War.

Some of the actions, I think, really should be like, say, with chips and so on, should be really interpreted as related to the defense policy challenges and the concern about Chinese military modernization and how that plays into the deterrence challenges in the Western Pacific. So I think the broad question is, how do you– for the US Defense policy as they see it is, how do you get to a situation– maybe this is more my take, how do you get to a situation of stable long-run deterrence on the security side of things as an assurance or a support for backing what the administration is always talking about or likes to call a free and open regional order, which really refers back to this kind of political and economic autonomy of countries in the region that they maintain an ability to trade with who they please, according to something like commonly observed rules of the road?

The administration released something called the Indo-Pacific economic framework. And they started talking about it in late 2021 and released the documents, I think, in early 2022. This is a set of talks oriented to, as I understand it, I don’t have deep insight into this at all, but talks on digital, on trade, including digital economy, tax policies, a set of other pillars that they are talking about with 13 countries comprising in the region, comprising something like 40% of global trade.

It’s a little unclear. I mean, the discussions are ongoing. And they say they want to have a set of results by November this year. It’ll be interesting to see. I don’t know if there are other panelists who are following this and could say something about it. It’s a different approach. And the administration’s too kind of traditional US trade policy, which traditionally, there was talk about and focused on trade agreements.

This administration, like the last one– and I’d say one of the big changes is neither the Republican nor the Democratic Party seems to want to talk about trade agreements at all. And they don’t even like to use the words. The National Security Strategy has a sentence, which I should have written down, but it’s something like we need to modernize or move past the free trade agreement approach. And they talk about fair trade and so on.

Whether this can deliver, we’ll see. I really don’t know. But it could be– well, it probably is to some degree just an acknowledgment of changes that make the institutional– set the inherited multilateral institutional trade setup which was already pretty sclerotic arguably, not that functional. But I’d be very interested to hear what other people on the panel then say. I’d stop there. [APPLAUSE]

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Thank you very much, James. Now, I turn to Tino. And I say as president of the Carnegie Endowment on international Peace, you’re going to save us.

[MARIANO-FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] No.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] And in fact, if these multilateral arrangements and agreements are sort of not so possible anymore, how do we go about moving forward? Or any other folk you choose.

[MARIANO FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] Thank you, John. And thank you, everybody, for being here. It’s just a treat after so much pandemic isolation to be in any event where I see real people. I should tell you, one challenging thing about being on this stage right now is the view is distractingly beautiful.

[LAURA TYSON] The view is very nice.

[MARIANO FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] With one exception, and that’s that Art and Architecture Building over there, our environmental building. You have to get rid of that. But aside from that, I’m very happy to be here.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] It’s an award-winning building, which says what architects really want.

[MARIANO FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] It’s insane. That’s the one thing more insane than the state of the world we’re talking about. How many of you are students? OK, well, let me begin with an apology, because, in some sense, our generation is in the process of getting ready to give you the keys to the world. And we’re not giving you a vehicle that is in great shape. But really, what I want to do in part to eventually get to John’s request, and I don’t have a formula to solve things, but to just put things in context a little and get the conversation moving towards what will help us get through this tumultuous era of economic fragmentation and tensions between the US and China is to zoom out and look at the very big picture.

So let me start by acknowledging some things that I take as a fact. It is a fact that the US and China are in the process of a massive fragmentation. Now, there’s some subtlety and nuance here that’s important. So trade between the US and China, bilateral trade, has never been higher at this very moment. So it’s not a complete break. But the technological side is an indicator to my mind of where things are going.

If you had asked me five years ago, whether I thought it was possible that the leadership of the US government would say on the record, not privately, not in a little dinner with Chatham House Rules, but on the record that their goal was to limit China’s economic rise five or six years ago, I would have said, I doubt that level of candor or directness. And that is what’s being attempted now. Now, that’s not lost on China.

And one of the interesting intellectual and policy questions that your generation will have to deal with for the students is what the elasticity is of technological innovation to policy change that comes from knowing that a major geopolitical power is trying to stop you from developing technology. Like, how quickly do you develop your own TSMC, your own lithograph machines, your own AI algorithms like leapfrog all of that? Or conversely, is there something– I mean, do we have the courage of our convictions, something in the secret sauce of a California, a place of immigrants, a place of openness, that creates a different kind of technological innovation story? So that’s one thing I’ll just put out there.

Second, I think it’s worth recognizing that much of what is driving any policymaker at the highest levels in the US– probably in China to some extent, but I’m more familiar with the US– is a little overdetermined. So if any of you traded places with Jake Sullivan or Gina Raimondo, you might do things a little bit differently. But I doubt that you would have complete freedom to totally rewrite the story. That’s to say that even if you’ve buried the party, even if you’ve buried the personality, there’s some degree of geopolitical pressure, economic reality, domestic political reality that hems in these policymakers.

That’s the part of the news. But the other piece of context that I think is crucial here is to think about what moment we’re at in human history. Everything you see around you, including the ugly environment award-winning building over there, is created and made possible only because of the Industrial Revolution. And that has been the tiniest fraction of human history. So if I zoom out a bit, the world does look depressing, difficult, painful, certainly if you’re in Europe and think about Ukraine if you’re Ukrainian.

But let’s remember that in 1950, literacy was about 50%. Now, it’s about 90%. In 1950, life expectancy was about 46 years. Now, it’s about 76 years. That’s the trend we’re on. So my frame to you is if I zoom out a bit, to me, the questions of economic fragmentation, the war in Ukraine, the frostiness of US-China relations, the economic dislocation and fragility people feel are all about disruptions on a path that humanity can and should stay on ideally to enormous progress enormous possibility. The fragility of the planet, climate change, it’s all the question of, like, how do we back ourselves into this corner? How do we get back on this path of innovation prosperity that we can share with the world?

Now, to be clear, there are some real impediments. Let me just go into that for two minutes, and then I’ll tell you what I think might be helpful going forward. The brutal realities of the war in Ukraine are not just about the Ukrainian people, obviously, not even just about Europe. They’re about the fact that we wrote a check as a world in 1945, 1947 roughly, around the time the UN was created, negotiated right around across the bay, that there would be a system to stop. Aggressive war from happening. That was never perfectly achieved.

But the scandalous reality of having a UN Security Council member be the party engaged in aggressive war is a particularly poignant indication that we have not– we don’t have sufficient funds to catch that check to channel Martin Luther King. So that’s on all of us. And it does highlight that the problems here are not just about Ukraine, they’re really going to affect potentially billions of people. Like, what does the world do when aggressive war occurs?

That has to be counterbalanced with a really brutal political reality if your taxpayer in Western Europe or the US, which is you’re shelling out $5 to $6 billion a month collectively to keep the economy of Ukraine afloat. And that’s not even counting the amount of money for the missiles, for the drones, for the millions of rounds of ammunition. So there is a question about how long this war can continue. But I don’t think it would be wrong to conclude that on the other side of this discussion, sitting in the Kremlin, are people or is a person thinking that time is on his side. So how does that look when you’re trying to limit aggressive war?

Second, the frostiness of US-China relations are not just a problem with respect to potential decline in growth rates. They also are on the minds of people like me, because there’s just an aggregate increase in the risk of an off the equilibrium path, dramatic, staggering conflict. And even a pretty minor one between the US and China, it’s going to go way beyond what the predictions indicate about just sort of a moderate loss and growth.

And I think it’s just important for us to recognize that even though the US and China have serious and important differences, and as a former US policymaker, I look askance and with concern that a lot of things happening in China, as I’m sure China does with respect to US. I just note that question of what is the risk of that off the equilibrium path event, particularly around Taiwan, but not exclusively. That’s got to be on our minds.

Third, every institution that involves thoughtful people trying to make choices about budgets and about the use of legal authority is facing a loss of confidence around the public. So people lose some confidence in the University of California or the California Supreme Court or the IMF or all of the above. And to me, this generalizes by saying, to a first approximation, no country with a very large population knows how to govern in this era very, very effectively.

We’re all trying. We all have ideas. We all have some things that go better than others. But if we’re not talking about Denmark or Singapore, I think governing at scale is really, really difficult. And so in the US, that means we take our chances with democracy. We do our best. In places like China that have a more authoritarian tradition, that means leaning into that tradition to some extent. But I think on both sides, what you see is a real question about how with this level of technological change and social media and just disruption and loss of trust you govern.

So where do we go from here? I would say five things I’d put on the table for discussion, all of them worth plenty of back and forth. The first is I would say, the war in Ukraine, the frostiness of US-China relations and the underlying causes behind them are important. But I would not want the world to stop thinking about the big picture questions involving how to keep technological innovation going, how to keep the Global South and the people who are poorer and more economically insecure in the developed world from feeling like they just have no stake in the system, how to deal with climate, biodiversity, water, et cetera. That deserves a ton of attention of the agenda despite all the other things happening.

Second, I would advocate for somewhat greater experimentation in domestic economic policies in different countries. This is my pitch for saying that you can be a little bit more flexible with the rules of trade and not necessarily get just autarky everywhere. I’m not in favor of big tariffs, to be clear. I think that global trade has been a big boon for human progress.

But we are a lot in each other’s businesses now. And I felt that a lot as a domestic policy White House official. Back in the day, when working on public health, transnational crime, tobacco policy, food safety, civil and criminal justice, almost nothing that I did that didn’t have a meeting with USTR attached to it. And I thought that was really telling and interesting. And I just wonder if the system might be sort of made more viable if we ask a little bit less of it to some degree. And I can say more about what that means.

Three, I think the multilateral development banks should have about twice as much capital to spend on infrastructure change in the developing world for climate and energy reasons. Fourth, I think the stuff happening around the eye is really interesting and exciting but requires careful attention. And I’m not sure that any one actor has all the right incentives, certainly not the private sector that’s developing most of the technology, even though they are potentially in a position to do some good things with it. And I suspect, by the way, that getting the governance and regulatory framework right, there would be a potential boon for billions of people who can benefit from the technology to deal with medical, educational needs.

Last but not least, I think all the geopolitical problems we’re talking about should be leveraged in some way. So on the domestic US side, concerns about geopolitics or driving interest in domestic investments in technological innovation, maybe starting to percolate into discussions about how to rethink our immigration policy. I think maybe a US-China degree of competition might also develop greater interest in both countries about how to appeal to the developing world and help them through the energy transition. I’ll stop there. [APPLAUSE]

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Thank you for really actually providing real insight on some possible directions. Laura.

[LAURA TYSON] So I think I’ll just throw a few things out there. I have been working with John. We did do a paper for Omidyar thinking about looking forward, thinking about the big structural drivers and uncertainties of the global system. And I will play off of my comments with John there.

But let me just start with something that occurred to me as I was listening to my other panelists. And that is the past dependency of where we are with China today in the United States. I don’t think people recognize, but I clearly recognize it, because I was involved in this part of the transition to the Bush administration in 2000. If you had talked to Condoleezza Rice at that time, what she would have said is that the major foreign policy challenge for the United States was China, was China.

And because we weren’t yet thinking about what was going to happen in the Middle East and insurgency and how we were going to totally flip, and we were simply going to focus on that, there is a growing– and it does grow over time, it was there in 2000, and it’s bigger now– a growing group of maybe different interest groups that really would like to reduce as much as possible US-China interdependence or would like to put as much pressure as possible on China to be like us.

There are religious groups. There are human rights groups. There are ethnic groups. For a long time, the business community was in the United States the major, I would say, voice for the importance of growing economic interdependence with China. But think about that, the incorporation of the United States, which made billions of dollars by labor arbitrage in China, by essentially producing their products at very low cost in China, using low-cost labor, selling it around the world, collecting the surplus, and giving it to their shareholders, giving it to their owners, not giving it too much to their workers.

So from over the course of, say 2000 to ’22, today, much of middle America and certainly the medical American workforce have seen the growing interconnectedness with China as a negative. It has hurt their wages. It has hurt their jobs it has hurt their communities. It has taken products that could have been produced in the United States and move them abroad. Those removed by the way by the companies, by the companies, not by nation states. The US didn’t move this stuff. China made it attractive place to do things, and US companies went there.

US companies started to get less supportive of the regime with China somewhere around the mid-2000s, really– I would say, no, more like around 2015, 2016. It was like, OK, they’re stealing our intellectual property. We knew that. They were always stealing our intellectual property. We used to get a better deal we used to get higher returns from the trade-off for us, the company I’m speaking now is that will let them steal the intellectual property. But boy, do we make a ton of money through our interdependence with China. We love it.

They became less and less convinced that the balance of returns worked for them. So a major, perhaps the major voice for easing US-China tensions, the business community in the United States, that voice has been lowered. That voice is no longer dominant in those discussions. And indeed, some of the companies are actually now on the other side. The national security companies are certainly on the other side. There’s this saying, OK, yeah, we can’t really depend upon having so much of the supply chain of semiconductors in Asia.

We put it there, by the way. The companies put it there. The companies put it there and say, probably, not a good idea anymore. Let’s bring some back. And the US government says, here’s a whole bunch of subsidies. Here’s a whole bunch of tax credits. Here’s a whole bunch of things that will help you bring it back, will help you bring it back.

So I just wanted to start there, because I think the history of all this matters. And I also will say what has been mentioned here is that the increasing frictions between the US and China, you cannot underplay the sort of change in the policy environment that President Xi himself has introduced. There is a change on the Chinese side as well. And I think you cannot and whenever I hear about Hong Kong, I’m reminded of that a lot of people look at what happened in Hong Kong and say, see, China’s got to do this. It’s just a matter of when they’re going to do it and how they’re going to do it. They did it in Hong Kong, and we let them do it. We let them do it. I thought I wanted to start with that view.

Let me talk a little bit about a phrase I’d like to be defined by this panel. How do you measure technological decoupling? What does that even mean? If everybody is working on the same AI technologies, the same digital technologies, the same nuclear fusion technologies, how are we– are we just going to do the same thing, but we’re not going to talk to each other about it? I really want to know what technological decoupling means.

That brings me to climate, where there at least is a recognition throughout this entire period of time of deteriorating US-China relations. There has been a sense that one area where we can work with them, and we should work with them, is on climate, because it’s a shared interest, completely shared interest, because we have moved from the biggest emitter in the United States to China being the biggest emitter in the world. So basically, we have the same problem. If we’re worried about the world carbon situation, we the big emitters have to figure out what to do about it. So shared interest, shared challenge because of the size of the emissions.

China has been doing some really, really interesting domestic policy, including its own carbon trading market on carbon. But here’s an area where it would seem to me that technological cooperation to deal with a shared challenge would make the most sense. And at the meetings, the last COP meetings, there was– the former Secretary of State John Kerry is now the special envoy on basically global relations on climate change, trying to work with other countries on common strategies and common technologies.

And he was very pleased that in his meetings with his counterparts in China leading up to the COP meeting, the Chinese were willing to be there with him, were willing to talk with him about it, were willing to be a presence in that meeting. So I think that we might look to the possibility of climate collaboration.

The National Security Council document mentioned at the beginning, a climate change is one of the recognized by the NSA as one of the major national security risks in the United States. So it’s not as if this is separate from national security consideration. This is a national security consideration. So that seems to me is another reason why we might be able to bring together the agencies on some kind of collaboration with China on this issue.

However, and now I’m going to go to the competition part of climate and green and talk about technologies. So part of the US switch in policy to attract production back to the United States, and employment back to the United States, and investment back to the United States through subsidies and tax credits, a motivation for that is basically job creation in the United States. It’s production in the United States. It’s investment in the United States. It’s not climate change per se. It’s not relations with China and national security risks of trading with China. No. If we want to have more good jobs here. And you hear President Biden saying that all the time. That is the way he couches a lot of these policies.

Well, if you do that, if you do that, you set off some kind of, I would say, tit for tat. Let’s say the positive side would be a tit-for-tat subsidy raise. We throw it a bunch of subsidies, and we are, if you look at the IRA. The Europeans who are talking about this throughout the Davos meetings look at the size and go, oh, my god, we’ve got to do that, too. We’ve got to throw a whole bunch of subsidies, because we need the green technology produced here. We need the technological breakthroughs in green produced here. We need the production of the green technologies produced here. We need the employment of deploying the green technologies produced here.

And so the countries, I think, the perspectives of the US, of China certainly, of Europe in the area of cooperation on a shared challenge of climate change, that cooperation is going to be hinged by or not hindered by but interface with competitive concerns. We want the technology produced here. So the competitive nature of the Industrial policies that regions of the world are putting together in a good cause to promote the production and services that lead to addressing climate change, that’s a good, good cause.

But there can be conflict in this. There can be trade conflict. There can be foreign direct investment conflict. The IRA, that piece of legislation that we are so proud of here, is discriminatory. It is absolutely discriminatory. It says if you produce it here, come on, welcome. We won’t discriminate in terms of ownership of production if you’re a German farmer, who wants to do it or a Taiwanese farmer, who wants to do it, Korean farmer, anybody, except Chinese. We do say except Chinese right now because of the national security risk. But it is discriminatory in the sense of location. And some of the IRA is actually in violation of the current WTO rules.

So the question then becomes, do we need a new set of international rules on trade and on investment? Maybe the simplest way to do it is to think about trying to divide rules for a particular kind of trade and investment. So let’s say, green. So there was a sector– there is a sectoral trade agreement in IT. It goes back to I think 1996, 1997. About 87% of the World Trade in IT is covered by that agreement. Maybe we need a write an agreement, which is not a whole new WTO, but an agreement on in the green space. That might be a possibility.

Some other places where I think there’s a possibility of collaboration or of international rulemaking in the green space, one would be disclosure, disclosure of carbon emissions. So now, there is a new international standard setting body that has been set up by COP, set up by the UN. And at the end of the day, what this is supposed to do is to insist on standardized credible information about carbon emissions at every point in the planet, at every point in the planet. So that basically then an investor or a company, investor in a company, who says I’m on net-zero, can say, yeah, well, you’re not really on net-zero. You say you are, but your emissions are nowhere near it.

So an international agreement and standards possibility, I mean, the standard body does exist. And it is putting together these standards. Right now, it’s totally voluntary. So the question is, could that become regulatory at some point and a global agreement? Another area where one might have at least a global agreement possibility or at least among some countries would be out a carbon tariff, a carbon import price protection. That is a possibility. So I will stop there.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] You don’t have to stop abruptly, but–

[LAURA TYSON] No, no, no. But that’s good. I think that’s pretty much where I was going to stop anyway.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Wonderful. [APPLAUSE] And Laura raises a very direct question, which is, if you will, that the coalitions and arrangements about technology in a technological autonomy and what we often call sovereignty in Europe, in fact, conflict with the kinds of coalitions that are needed to try and deal with the problems of climate.

And part of the question, are there ways around it? Obviously, you raised the issue of doubling the investment in multilateral investment institutions has one strand of that. So I’d love to get the reactions from the rest of you to some of the issues that are out on the table. Maybe we do a very quick go around, Pierre, James, Tino, and then try and open this up to conversation.

[PIERRE OLIVIER GOURINCHAS] Well, thank you. I thought this was absolutely enlightening and fascinating. Let me just offer a few reactions to some of the things the other panelists have mentioned. So James was asked– was making the point, which I fully agree with that if we were to get in a situation of military conflict between the US and China would be in a very different environment than the kind of economic decoupling of fragmentation scenarios that I showed you. And of course, this is absolutely true.

And while there might not be a concerted effort at economic decoupling, I think a number of the panelists have pointed out whether– Tino talks about of equilibrium, and Laura talks about path dependency. I mean, the danger here is what we at the Fund call runaway fragmentation that you do something because you have some narrow objective in mind, maybe it’s about targeting some advanced semiconductors and trying to curtail progress that one country is doing in that direction. And this is on the grounds of national security.

But the world doesn’t stop there. It’s very unlikely that other countries would just not respond at some point or another. And then you get into another round. And then shocks happen. And then things can take a turn for the worse. So I think this notion that we are in a more fragile world is important to keep in mind.

Related to that, the question I’d like to ask James is when we’re thinking about the China-US rivalry, I mean, I think we have to– I mean, Laura talks about dependency. But really, this is the emergence of this multipolar world. It’s the rise of a major power on the economic and global scene that we’re seeing. And it proceeds in fits and starts a little bit like plate tectonics, that nothing moves for a while and then you get one of the plates moving as we’ve been reminded in a horrific way recently with Turkey and Syria.

So I think this is the dynamics that we’re seeing here. And if we’re thinking about that emergence of this multipolar world, it’s a challenge. It’s a challenge, because, I mean, if I channel or if I think about my colleagues who are more international political economist than myself, does the world need a hegemon or not? That’s sort of the question that is in the background.

And you could make the world more stable by having blocs. You could have blocs within which there is a local hegemon. And that’s a stable world in a sense in some dimensions. Or you can try to have a more integrated world in which you don’t. And that means that the rules need to be defined, and so the engagement needs to be defined. And so that’s I guess the question is what kind of world do we want to build?

And here, at the Fund, we’re sort of facing this reality. We’re seeing that there is this push away from multilateral rules, whether we’re looking at the WTO and trade issues or whether we’re saying, the very fact that there is in a major war on the European continent right now. And we have to think about, how do we engage? How do we try to maintain and make progress on the multilateral agenda?

And our approach is to try to be very pragmatic. It’s try to realize that in the current environment where the wind is– we’re facing significant headwinds, we can’t really push on all these things at the same time. So we have to maybe be nimble and adjust. And I think that goes in the direction of what Laura was highlighting in terms of maybe sectoral agreements, where you try to push on something that is about green technology, or maybe try to have multilateral agreements on common goods where everyone agrees. And you might put climate in that bucket. You might put some other things.

On some other issues where some countries might agree but not everyone, you can go to your lateral way. You could try to have some agreement that are open and non-discriminatory where countries can join, and you try to build a coalition that way. And then the hardest part is on situations where you are head-to-head and countries don’t are really on very different paths and are not willing to make progress.

And here, of course, countries will motivate what they’re doing by national security and sovereignty. But I think we can still have a conversation about at least doing a spillover analysis, trying to think about what decisions individually might– how they might impact the rest of the world. What was quite striking I think in the context of the IRA is the extent to which these were a number of measures that were taken, in part, as Laura described, to try to satisfy some domestic objectives but without really necessarily taking into account the way it would impact some of the US allies, the European firms, et cetera, that came later.

And so doing this kind of analysis upfront, being cognizant about the spillovers is something that maybe can help put some guardrails. You might think that, for instance, for things like food exports or access to medicine, if you think about a pandemic, those are things where we want to have safety corridors. Even for national security reasons, maybe we wouldn’t want to put restrictions on this. Let me stop here.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Thank you. Before we turn to James and to Tino, I want to remark that we are holding the conversation as Americans in California. If we were holding this conversation in Berlin or in Paris or in Copenhagen or in Finland, the concern about technological risk and technological domination would only partly be about China. It would be about American big tech companies. And part of the question would be, how do we in fact establish our own autonomy and sovereignty in the face of this? And how do we handle this conflict going on between the United States and China without getting squeezed in between?

Now, I don’t think today we’re going to be able to really engage with that issue, because we have a whole range of other topics on the floor. But I think it’s absolutely a critical one that in a different context, perhaps all of the four of us and others can, in fact, take up. I see one of my friends from Denmark nodding away at that very, very assertively. But I don’t want to distract you from what you might have wanted to say, James, but I did want to make that point on my behalf.

[JAMES FEARON] Thanks. Well, I’m interested by the idea, Pierre-Olivier, of this runaway fragmentation. And I’d be curious to hear and read more about that, not to dismiss it at all. I mean, I’m obviously in zero place to do that. I guess, I do wonder about it. I mean, what I know from the IR, IPE side is a lot of our thinking is really driven by kind of the Specter of the 1930s and the fear of a collapse, a real shutdown of trade.

And you guys are expert on this kind of thing. But I wonder the nature of– many things have changed from the 1930s in the trade sector and the depth and global value chains and the effects of these. I wonder– it’s kind of a question, have you thought through how would we see runaway fragmentation currently? Do you have evidence from the– I’m sure you guys have been studying the economic impacts of the war in Ukraine.

I mean, I think a big conflict in the Western Pacific would be an entirely different thing. But nonetheless, it would be– I’d be very interested to know, I mean, how– obviously, the word Ukraine has been– the costs are stunning at the level of human life, injury, refugees, dislocation in both Russia and Ukraine. But on the economic side of things, how big are the kind of hits to GDP that we’re looking at there? And how is it affecting trade patterns in terms of some of the issues, you’re talking about resilience and substitution?

The other thing I’d say is ignorant to speak to Laura’s– or what Laura particularly but others raised in terms of the climate issue, this is a real– you definitely see– I think if you look at their documents and how they’re talking, the Biden administration understands that this is a tough circle to square or square the circle. How does it go? I don’t know, but on the one hand, I want to say, this is not– climate is not something we can make progress on without high levels of international cooperation. And they say– which I think just is the right thing to do– we are ready and want to talk about cooperating, and the door is open.

But at the same time, they’re saying, we also– the phrases go like, the PRC is the only country with the means and intent to revise the global rules based order and want to mobilize and focus on competition. And a not uncommon response by Chinese diplomats is, you can’t do both. They want to say, OK, you want help on climate, and I don’t know. I’m not quoting here. But effectively, it would be adopt our position on Taiwan.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] So with that, I’m going to ask a question. Are we absolutely obliged to stop at 1:30? Or can we take 10 extra minutes? We can. We have– so–

Can’t we straight to the questions–

Yeah. I think–

Go ahead. Do you want to make–

No. Just go straight–

So let’s open this to question. You can go to the mic–

[LAURA TYSON] There’s a microphone on either side.

Hey, Henry. It’s Henry.

There’s a microphone on your side.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Please also say who you are, where you’re from even if I already know.

Yes.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] I’m Henry Farrell. I’m at Johns Hopkins University. I’ve got a question for Jim, which picks up on something that Tino said. So Tino said that it was incredible to see the United States effectively announcing that it wanted to close China down or something. I understood what you were saying, it seemed actually a little bit different from that. You seem to be arguing that from the US perspective, this is not about trying to keep China down. But these are technologies with specific military applications, which the US is trying to sort of prevent China having similar access to.

But I guess the question I have is, to what extent is Tino’s comment controlling here. In other words, if you’re China, and you read Jake Sullivan’s speech back in September, where he more or less said that the US wants to keep China as far back on what he called foundational technologies as it could, China is going to read this obviously in very different ways.

And are there ways in which the United States, if what you’re saying is correct, can credibly communicate and can create some kind of a modus vivendi with China that China is prepared to accept? Or alternatively, do we face the kinds of dangers of spiraling that you talked about briefly in the presentation because of fears of a more general desire to just keep China from achieving what it wants and believes that it is entitled to achieve?

Now, as chair, I’m going to say we did not use a timekeeper. We didn’t cut people off, but I’m going to insist that we keep responses at this point short and direct, so that we can get as many questions in as possible.

[JAMES FEARON] Thanks, Henry. It’s a great set of questions. My impression– I think, Laura said something which resonated in either this or related context. It’s not like– I think if you could look into the views of high level Biden administration foreign policy officials, you’d get a spectrum. And I think that the Jake Sullivan thing you’re referring to and some of that language on technology, it’s not so much like– well, I’d like to think, and I think some people would say, it’s not about keeping China down.

It’s that we have come to the realization that this was a one way street. And that they were admitted to the WTO and then exploited the rules of the game and haven’t played by the rules. And so we’re looking for reciprocity, not maintaining hegemony. That might be a take there.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Laura and I’ve held some conversations with some of these people. Do you want to comment on it at the–

[LAURA TYSON] There’s a spectrum of views and there’s a very, very serious split. I mean, it’s not just a spectrum of views. But I mean, if you talk to people from the National Security Council about the semiconductor policy, it is essentially war with China on semiconductors. Period. What Jake said exactly reflects that view.

If you talk to people in the Commerce Department, they’re talking about the need to build, rebuild the semiconductor fabrication capabilities in the United States, because we need to have a more competitive supply chain. And I think that’s a valid goal. So I think there’s just loggerheads right now in terms of the administration’s views on this. And I don’t think the National Security Council is weighing the economic consequences. That’s not their thing. OK. National Security is their thing. We’re not worried about the economic consequences.

Tino.

[MARIANO FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] Just super briefly, I cut my teeth as an assistant professor working quite a bit on how the legal system struggled and generally did not do a really good job of ring fencing the concept of national security. And if that’s true in the legal system, its way true in technology. I think, we’re in a world where with advanced semiconductors and AI, at least, maybe even on the bio side, I think everything pretty much is dual use, and I think it’s the core of the problem you’re raising.

[LAURA TYSON] Yeah. Great.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] Do you want to add anything to that? Let’s turn to another question while we still have time for that. Sir, your name and where you’re from.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Thank you very much. This has been a very tremendous panel. My name is Haikun. I’m currently a senior studying economics.

I just wanted to I guess question the rhetoric of the panel a little bit. I’m wondering why is there almost a sense of inherent antagonistic perspective when it comes to talking about the role of China. Like, why is it a perspective of competition rather than collaboration? And then also the same sense of antagonism when it comes to the private sector. Because isn’t the goal about global integration, like your talk yesterday?

[JOHN ZYSMAN] What I’m going to do is take all three of these questions very briefly so that we get one round of responses. We get an extra five minutes, but we still need to do it that way.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Great. Thanks. My name is Ping. I’m a first year MBA student. My question might be a little long, so I wrote it down. So I thank these panelists. You guys mentioned the importance of technology, innovation, as well as like climate cooperation. But I’ve never seen a higher rate of progress other than the Cold War. So like a controlling environment of competition can be helpful in this situation.

But, as we can see, the war in Ukraine, there has been a tremendous amount of humanitarian crisis, environmental crisis, as well as economic disruption. So how does the both parties in this situation– China and the US– in a such volatile environment, both politically and socially, how do the policymakers keep the tension under the boiling point? And if there’s anything the policymakers can do to control the tension.

All right.

Thank you.

Sir.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Hi. My name is Anchu Jin. I’m originally from India, but I’m an MBA student here at Berkeley Haas. And my question is sort of opposite of the previous question.

So I wanted to ask, basically, there’s this theory which was popularized by Professor Graham Allison of Harvard. It speaks of the Thucydides’s Trap, which is that there’s a dominant power, which is the US, and that there’s an emerging power, which is China. There’s always sort of a position of conflict between the two. And that conflict, there might be a flashpoint, which is maybe Taiwan or Hong Kong, but there is a natural tendency for conflict.

So how much do you ascribe to that view? And if you ascribe to that view, do you think that the US should take actions early and be more aggressive in combating China?

[JOHN ZYSMAN] If I understood– and there’s one last question behind you, so let’s take the question. But I was going to say, if I understood, you’re asking about basically Graham Allison’s view of the matter. And the answer is carefully. Carefully. I mean, that’s what the basic position he takes. Ma’am, to the microphone so we can hear you, please.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Hi. My name is Charlotte. I study economics here. I’m wondering if the United States and China might– how we might be able to navigate the conflicting needs for collaboration over climate and tech decoupling at the same time in terms of developing fusion technology.

[JOHN ZYSMAN] I’m going to give a quick answer to a couple of these and then turn it– the fusion technology issue is really an open-ended one, where the question is it’s basic research– how do we structure collaborative basic research. And it’s quite a different problem from the semiconductor or other kinds of things. There may be some hope in that.

But a number of us, in fact, were involved in one way or another in the WTO– entry of China into the WTO. And I can assure you that the conversations held at the time and the outcomes were quite radically different, which is I think part of what has sparked some of the concerns. But with that, let’s– we have– we’re being granted a 5-minute access here.

[MARIANO-FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] So I’ll jump in really quickly.

I can’t answer all of them. But just very briefly on the Thucydides’s Trap, I think Professor Allison has some neat ideas there. I would read Thucydides’s work actually a little differently and suggest that there are ways to avoid certainly the worst conflicts. But I think he’s right to note that this is a period of remarkable peril potentially and concern, which leads me to answering the first question.

And I would just note, look, the kind of world that I think we all want to live in is one where there’s plenty of room for the US to prosper, for China to prosper, while we recognize that they disagree about some basic things. My own view is that I try to take the world as it is, not as I’d like it to be. So if you look at that first meeting between Jake Sullivan, Antony Blinken, and their counterparts at the very beginning of the Biden administration, there’s no way to describe it other than it’s contentious.

[LAURA TYSON] Yes, contentious.

[MARIANO-FLORENTINO CUÉLLAR] And then briefly on the private sector, I think the private sector helps the world thrive, but I think there need to be some rules of the road. And what they should be and how to get them to the right place without squelching innovation is really the key question.

Well, I–

[PIERRE-OLIVIER GOURINCHAS] Very briefly.

Very, very briefly. I mean, I think obviously on the first question, I think a place like the fund is, of course, trying to foster engagement and multilateralism, and we’re trying to be a place where exchanges can take place. And that helps to address the second question as well, which is how to avoid getting to the boiling point. I think you keep working together. You try to engage and gauge where you can rebuild trust.