How should we understand violence against trans/queer people in relation to the promise of modern democracies? In their new book, Atmospheres of Violence: Structuring Antagonisms and the Trans/Queer Ungovernable (Duke 2021), Eric A. Stanley, Associate Professor in the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, argues that anti-trans/queer violence is foundational to, and not an aberration of, western modernity.

Their other projects have included the anthology Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, co-edited with Tourmaline and Johanna Burton; and the films Criminal Queers (2019) and Homotopia (2008), in collaboration with Chris Vargas.

For this visual interview, Julia Sizek, Matrix Content Curator and a PhD candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Anthropology, asked Professor Stanley about their research, drawing upon images and videos referenced in the book.

Your book begins at the site of the death of Marsha P. Johnson, a pioneering transgender activist, and trans/queer death is generally the subject of the book. In what ways has death become central to understanding both LGBT history and trans/queer people today?

The book does dwell in the space of death, and the first pages include a note on “reading with care” so people will be aware of its content. However, my attention to the work of violence is not because I believe it to be the limit of trans/queerness but because, under the order of the settler colonial state, harm is any and everywhere. What this means is that we must work to understand the various ways violence delineates trans/queerness if we want to end it. To this end, I investigate how racialized anti-trans/queer violence is foundational to and not an aberration of the social world.

That said, rather than simply argue that we are “against violence,” I reposition the demand by way of a question: what constitutes the time of violence for those living in the crucible of total war? In other words, saying that we want to respond to specific instances of violence is not enough if we have not rendered unworkable the structures that do not simply allow it, but mandate its continuance.

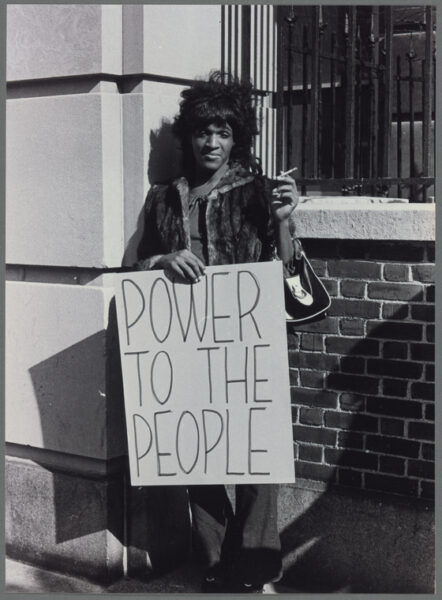

This is one of the many lessons that I continue to learn from theorists like Marsha P. Johnson. She was a marginally housed radical organizer whose Black trans politics were fashioned from living in and against the anti-blackness of a transmisogynist world. Her death, which was deemed a suicide by the NYPD, remains under speculation by her friends, who believe it was perhaps a violent trick or even a police officer who murdered her. While the case of her death has become a focus for organizing, Marsha’s commitments — her life in struggle — instruct us to organize against the conditions that stole her from the world.

While direct attacks against trans/queer people are one focus of the book, I also theorize that the state perpetuates violence against trans/queer people through paradigmatic neglect. We can look at trans/queer houselessness, incarceration, and the ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic to see the ways inaction is, perhaps counterintuitively, an active process. It is, I believe, in these spaces of seeming contradiction where power becomes most visible.

In this video, Sylvia Rivera, a contemporary of Martha P. Johnson, is met with resistance by the crowd when she takes the stage at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day celebration. Today, she is considered to be a trans icon. What does Rivera’s acceptance today reveal about how we consider LGBT history?

This video depicts transgender activist Sylvia Rivera’s monologue at a demonstration in 1973.

The introduction of my book, River of Sorrow, attempts to think about this antagonism. The amazing documentation of Sylvia fearlessly climbing the stage at this celebration gathers up so much of what the book theorizes. Sylvia was a Puerto Rican trans organizer, sex worker, anti-imperialist and one of Marsha’s closest friends. She was not given space to speak because cis lesbians and gays diagnosed her, and all trans women, as perpetrators of a misogynist culture by way of their identities. The transmisogyny of the event organizers who attempted to force her physically and ideologically off the stage tragically still lives in the ongoing harassment of trans people in general, and trans women specifically, by Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs). Not unlike anti-trans “feminists” of 1973, today we see trans people attacked much more than the patriarchal order they blame us for reproducing. Luckily, Sylvia was able to eventually take the microphone that day, and as you can see, she then delivered a devastatingly beautiful speech about the importance of not leaving behind those hidden by calls of “gay respectability,” namely trans/queer people of color in jails, shelters, and other “street queens” like her and Marsha.

The mainstream LGBT movement that Sylvia declared war against continues its legacy of assimilation in our current moment. Yet what is different, and perhaps even more dangerous, is that it now primarily terrorizes through incorporation. What this means is that, rather than working through exclusion and exile as it did in 1973, we now see the inclusion of those historically forced out not toward the end of reorganizing normative power, but to maintain it. The goal of inclusion is not to challenge the political order, as we are often told, but to extinguish radical critique and our dreams of freedom.

This dispossession through incorporation was again clarified after I finished the book and I noticed that the “all power to the people” photo of Marsha was being sold on a shirt at Target during their rainbow-washed June. The brutal irony is that they were selling the image of radical Black anti-capitalist action while underpaying their workers and racially profiling Black people in their stores. They want Marsha’s image, but they don’t want her. It’s this knot that I’m trying to apprehend in the book, so that we might find a way out.

This photograph was taken in 1992 at a political action by ACT UP, in which activists flung ashes of loved ones on George H.W. Bush’s White House lawn and transformed an act of grief into a political act. How does this act combat what you call “necrocapitalism”?

The ashes action leaves me undone. While political funerals were often organized by ACT UP and many other groups, this one harnessed the brutal eloquence of those forms of protest with the material act of “returning the dead” to the house of their executioner, specifically Bush’s White House. Here, friends, lovers, and families marched with boxes of ashes toward the White House under threat of the swinging clubs of mounted DC police, and then once they arrived at the gates, they tossed the remains onto the green of the lawn.

One of the practices developed by ACT UP was to name governmental inaction as a method of active killing. The disappearance of their loved ones was the unfolding of what Ruth Wilson Gilmore might call “organized abandonment,” instigated by a straight state that understood HIV/AIDS as the wish fulfillment of those already damned to hell. This idea that HIV is the materialization of God’s wrath might circulate less openly today, but the logical structure of this belief — that a virus is the punishment for wrongdoing — maintains the crushing stigma many still endure.

The desperation in the videos and photos of the action overwhelms. Revenge and mourning meet in the act of exhuming bodies. While the open secret of mass deaths from AIDS-related illnesses was spoken in quiet whispers and hidden under homophobic silence, here ACT UP materialized their loss in the form of ground bones, the remains of trans/queer life, scattered to the winds so that their pain might become all of ours.

Through thinking with this action, along with the murders at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, and the longer colonial history of HIV and current practices of blood banking, I develop a theory of necrocapital. Here I work with, and sometimes against, materialist feminists and others who have helped us understand the centrality of reproductive labor. With necrocapital, I’m paying attention to how speculation is not tied exclusively to the category of “life,” and indeed financialization has opened the entirety of the worker, even in death, to increased profits. One of the reason ACT UP’s direct action is so powerful is because it materializes the symbolics of trans/queer blood — the feared yet valued substance that is, at least under the logic of a phobic social, a vector of death. Here it is returned as a bio-strike, a labor stoppage, and a refusal to privatize our grief.

In this short film produced by the Barnard Center for Research on Women, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, a trans activist, discusses how her personal activism has taken a new form. She says that, “on a personal level, what I did was change all of my identification back to male” as a way to highlight her transgender identity and “strike back.” How do you read this “striking back,” and what does it show us about the relationship between trans people and the state?

Major’s irreverence for a world that demands respect but delivers none shows us that what is offered is not all that is available. Through a reading of her words and Tourmaline’s film, I suggest that her ungovernability — her life in refusal — is a pedagogy of Black trans sociality, an escape hatch out of the dreadful pragmatism of the current order. Importantly, as with Major, Marsha, Sylvia, and many others who appear in the text, I’m emphatic that they are theorists of trans life and not simply examples of it. This is necessary if we are to build a trans study that at least attempts to disorganize the organization of cis knowledge production.

Among the ways Major offers us this gift is through the story of her IDs. At one point, she switched her IDs from “male” to “female,” as many trans women do in hopes of decreasing harassment by those who demand papers. But then the short film repositions the narrative of transition, as she “switched them all back” to “male” because she is a transgender woman and she wanted to be known as such. She is clear, and I also underscore this in the book, that she is not making a prescription, but this “personal act” was, as you noted, one of her ways of “striking back.”

I’m dedicated to charting these otherwise minor acts, moments of rebellion and striking back that might slip past the telling of revolutionary social change. This is important as it not only connects to the larger moment histories, but as Majors makes clear, it’s where the force necessary to continue to struggle is often found. For her, community care and sedition fall into each other and build out an underground of laughter and beautiful negation.

Your book concerns questions of death and violence against trans/queer people and asks readers to confront scenes of death and violence. What were some of the challenges in representing anti-trans/queer violence in this book, and what alternatives do you imagine to trans/queer death today?

This is a central concern of the book and an excellent question. However, throughout the text, I am unable to reconcile the fact that representing violence and allowing it to disappear are both, in different but related ways, among the technologies that ensure harm continues. Instead of assuming I might know the answer, I hold this contradiction with as much love and precision as I can to move through it under the banner of collective liberation. Methodologically, I don’t represent, at least in image, the violence I theorize. I do, however, at times narrate the scenes, as I believe we must work to understand its world-shattering force if we are to stop it. The answer then cannot simply be to look away, although we all must do that at times to preserve enough of us.

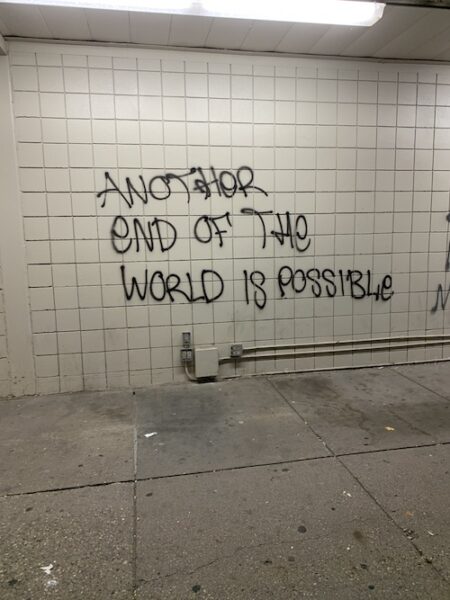

Yet what I believe the project must be, if we want to “end violence,” is the destruction of the racist anti-trans/queer social that has taken so many and continues to threaten the very possibility of anything else. If, rather than an aberration of settler modernity, these woven forms of terror constitute the world, then I ask, with Frantz Fanon, “is another end of the world possible?” I’m not sure. I do know that we must continue to think, which is also to continue to learn that, as Major reminds us, there is abundance here and now. Following the ungovernable, among our tasks is life’s radical redistribution and the abolition of the world as it is. Rather than defeat, we must also know that there is a long and unfolding tradition of trans/queer action that builds a world beyond this one, where we might all feel the safety and joy of ease.