Every year on April 23, the monastery of Aya Yorgi (St. George)—on the island of Buyukada, in Istanbul—attracts thousands of pilgrims, who mix with vendors and artisans along the path to the church situated atop a hill. Inside, Greek Orthodox priests perform mass for the gathered congregation. But the congregants themselves are not, for the most part, Greek Orthodox. On that day, it is mostly Muslims and Christians of other denominations who crowd inside the church to hear mass, offer prayers, and light candles that honor St. George.

This annual ritual might appear surprising to a contemporary observer accustomed to defined devotional boundaries dividing religious communities, but the eastern Mediterranean is dotted with such sacred destinations that bring diverse groups together in common veneration. Dr. Karen Barkey, Distinguished Chair in Religious Diversity at the Haas Institute and a professor in Sociology, is studying these sites and telling their stories with her colleagues to inform both scholars and the general public on the dynamics of religious tolerance and interaction in the region.

This annual ritual might appear surprising to a contemporary observer accustomed to defined devotional boundaries dividing religious communities, but the eastern Mediterranean is dotted with such sacred destinations that bring diverse groups together in common veneration. Dr. Karen Barkey, Distinguished Chair in Religious Diversity at the Haas Institute and a professor in Sociology, is studying these sites and telling their stories with her colleagues to inform both scholars and the general public on the dynamics of religious tolerance and interaction in the region.

Barkey arrived at the topic of religious tolerance through her research on the history of the Ottoman Empire and the strategies that its governments embraced to maintain authority. Her book Empire of Difference, published in 2008, examines how the religious toleration commonly associated with the Ottoman Empire emerged through the state’s efforts to gain legitimacy—and through religious communities’ own distinct practices of coexisting. This led Barkey and her colleagues to consider how that “toleration” manifested as “tolerance” in local social interactions among diverse religious groups and practitioners.

Perhaps no social practice better embodies those cultures of religious tolerance than the sharing of the same sacred spaces like churches, mosques, and shrines among devotees from different faiths. Together with colleagues, Barkey began analyzing places like the monastery of Aya Yorgi as a way of understanding that tolerance through the Shared Sacred Sites project, funded largely by the Henry Luce Foundation. The project has expanded into several related initiatives that connect fieldwork, analysis, and public engagement.

The multiple goals of the Shared Sacred Sites project converge in the Visual Hasluck initiative, a project that uses digital humanities methods to present fieldwork on sacred sites in an accessible and engaging way. Barkey and her colleagues wanted to draw more attention to one of the foundational works in the study of sacred sites in the Ottoman Empire, Frederick Hasluck’s Christianity and Islam under the Sultans, an archaeological analysis of religious interaction whose methods made the book far ahead of its time when it was published in 1929.

The multiple goals of the Shared Sacred Sites project converge in the Visual Hasluck initiative, a project that uses digital humanities methods to present fieldwork on sacred sites in an accessible and engaging way. Barkey and her colleagues wanted to draw more attention to one of the foundational works in the study of sacred sites in the Ottoman Empire, Frederick Hasluck’s Christianity and Islam under the Sultans, an archaeological analysis of religious interaction whose methods made the book far ahead of its time when it was published in 1929.

Barkey and her colleagues believe Hasluck’s methodology warrants renewed attention. “Instead of trying to trace clear-cut boundaries and categories, he explores sacred sites through a condition of mixing or ambiguity as his starting point,” explain Barkey and Dr. Dimitris Papadopoulos, who has conducted fieldwork and developed the site. Hasluck focused on interactions among groups and on the ambiguity of religious identity, eschewing the “fixed categories of religion, ethnicity and identity” that cloud any attempt to clearly understand shared devotional sites.

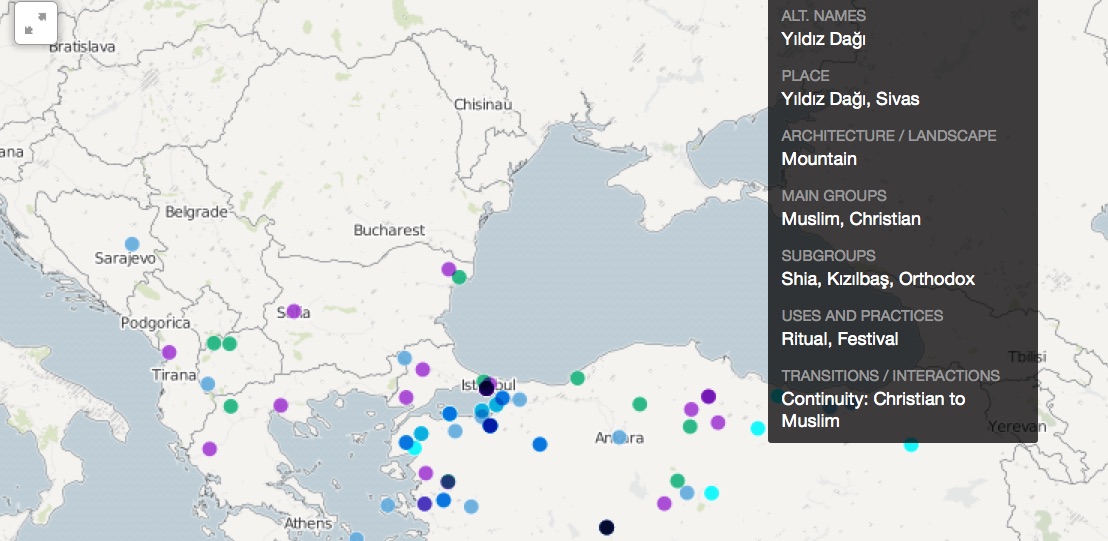

Barkey, Papadopoulos, and their colleagues turned to digital humanities methods to present the insights from Hasluck’s work to a new audience. They have exploited a range of possibilities that these methods offer, from computational text analysis to parse information from the book itself, to digital mapping and network analysis graphs to visualize the conclusions from Hasluck’s research.

They started with a digitized copy of Hasluck’s book in the form of a text file, and used free open-source digital tools like Unlock Text to automatically identify names of specific locations mentioned within. They used online dictionaries of historical location names to match Hasluck’s placenames with current names, and supplied information on the significance of the holy site at each location. With a database of that information and the coordinates of each location, the team developed detailed maps embedded with information on the groups and practices that render each site sacred.

The site also hosts interactive network visualizations, which graphically show the links between key terms in the text, such as names of saints or identities of groups, and those that follow or precede them in sentences. This can reveal, for example, how certain saints might be associated with certain blessings, or how particular sites are related to particular groups, in ways that may not easily be recognized through the book alone. As the project progresses, more recent ethnographic information can be incorporated into the datasets.

The Visual Hasluck site invites any visitor to be challenged by the complexity of sites that do not fit neatly into received religious categories. In a series of “Micro Essays” hosted on the site, Barkey and her colleagues explain new connections that their tools have uncovered. Through their network visualizations, they were able to discern how Hasluck understood the relations among particular groups. They clarify, for example, how the Kizilbash people of rural Anatolia were considered a subgroup of a larger group, but were identified particularly by their relationship with the countryside, rather than by their beliefs or theology.

Barkey and her team are developing n exhibit on Shared Sacred Sites in the Mediterranean that they hope to showcase in international locations over the next few years to insure that general audiences are able to appreciate these spaces as testaments to tolerance—and as challenges to ideas of fixed religious identities. Indeed, beyond benefitting scholars, Barkey and Papadopoulos are confident that bringing Hasluck to modern audiences will help promote understanding about religious identities and conflicts in Europe and the Middle East at a moment when they are taking center stage in global affairs and media coverage. “In light of current crises in Europe and the Middle East and dominant discourses of religion-based conflict and division,” they write, “it is critical to return to this text with a new set of eyes.”

Top image from Shared Sacred Sites.