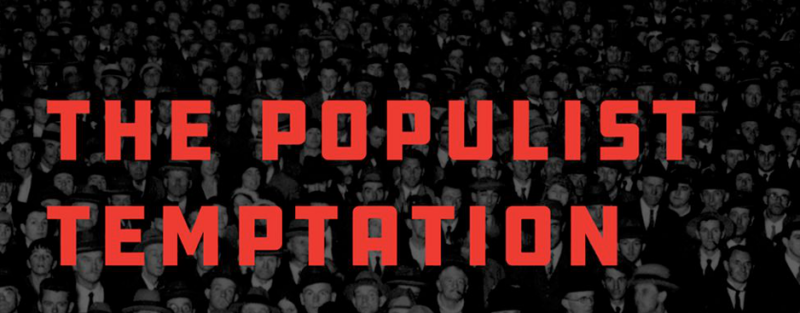

Populism—a political ideology that vilifies economic and political elites and instead lionizes ‘the people’—has spread like wildfire throughout the world. In his recent book, Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era (Oxford University Press), Barry Eichengreen, George C. Pardee and Helen N. Pardee Professor of Economics and Political Science at UC Berkeley, examines the recent resurgence of populism around the world and places it in a deep historical context.

Populism—a political ideology that vilifies economic and political elites and instead lionizes ‘the people’—has spread like wildfire throughout the world. In his recent book, Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era (Oxford University Press), Barry Eichengreen, George C. Pardee and Helen N. Pardee Professor of Economics and Political Science at UC Berkeley, examines the recent resurgence of populism around the world and places it in a deep historical context.

He also explores possible responses to the “populist temptation”: “A first step is for policymakers to do what they can to reinvigorate economic growth, giving young people hope that their lives will be as good as those of their parents and older people a sense that their lifetime of labor is respected and rewarded,” he explains, in a preface to the book. “Equally important is that the fruits of that growth be widely shared and that individuals displaced by technological progress and international competition are assured that they have social support and assistance on which to fall back. Assuring them starts with acknowledging that there are losers as well as winners from market competition, globalization, and technical change, something that economists are taught at an early age but which they have a peculiar tendency to forget. It continues with acknowledging that economic misfortune is not always the fault of the unfortunate. It concludes by putting in place programs that compensate the displaced and by providing education, training, and social services to help individuals adjust to new circumstances. This is not a novel formula. But if its elements are commonplace, they are no less important for that.”

Professor Eichengreen will be discussing his book in an upcoming “Authors Meet Critics” event, to be held on October 3, 2019 at 4pm at Social Science Matrix. He will be joined on the panel by two fellow UC Berkeley faculty members: Paul Pierson, Professor of Political Science, a renowned specialist in populism, social theory, and political economy; and Brad DeLong, Professor of Economics, a distinguished economist who served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Economic Policy during the Clinton Administration and is currently a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. (Please RSVP here to attend the October 3 panel discussion.)

We asked Professor Eichengreen some questions in advance of the panel. (Note that his responses have been lightly edited.)

What exactly is this political category called populism? How can it be so capacious that it encompasses Bernie to Trump to Modi? Is it even a political ideology?

As I say in my book, efforts to define populism remind one of Justice Potter Stewart’s definition of pornography: “I know it when I see it.” My preferred definition is a political movement with anti-elite, authoritarian, and nativist tendencies. Since populist movements combine these tendencies in different ways, there are different variants of the phenomenon: populist movements of the left, which emphasize the anti-elite element, and of the right, which emphasize hostility toward foreigners and minorities.

You write that populism is activated by “economic insecurity, threats to national identity, and an unresponsive political system.” How is it that the confluence of these three factors leads people to turn toward populism? Are there other factors involved, such as educational disenchantment?

There’s a long-standing, active debate on the relative importance of economic grievances and identity politics. From the subtitle of my book, and from my disciplinary background, you’ll guess that I have a tendency to privilege economic factors. But I would acknowledge the importance of identity concerns. In fact, I have some related research suggesting that the appeal to voters of populist messages lessens with educational attainment. I’ll be happy to talk about that.

Are there inevitably within populisms authoritarian tendencies, as political scientists such as Princeton’s Jan-Werner Müller have suggested?

As my own preferred definition of populism (above) suggests, I agree with this assessment. Populists of the left are impatient with technocratic governance, populists of the right with diverse constituencies. Both see appeal in so-called strong leaders with authoritarian tendencies.

You write that populism in the U.S. is moving us away from the “constructive policy responses to the problem of economic insecurity whose absence gave rise to that populist tendency in the first place.” How can we get out of this cycle?

Without necessarily endorsing a candidate or candidates whose slogan is “I have a plan for that,” a critical element is for leaders, actual or potential, of mainstream political parties to develop and then explain clearly, in detail, why their proposed policies are in fact constructive responses to problems of economic insecurity. Then it’s necessary to mobilize the social solidarity needed to implement such plans.

What follows populism, typically? Does history suggest a common pattern?

No, I point to examples in my book where disenchantment with populist leaders who had offered flawed policy suggestions leading to failed responses was followed by a descent into something worse, but also cases where “the center held.”

The coming years seem likely to bring significant labor displacement by AI and other technologies. What recommendations would you have for policymakers to address the social changes likely to result from this shift?

I have a chapter in the book about the relative importance of technological change versus China, NAFTA and emerging markets generally in contributing to labor displacement. I conclude that technological change has been the main factor in the decline in the share of employment in manufacturing for three or four decades now. There are, alas, no quick fixes. To talk our own book, as it were, investments in education and training, including lifelong learning, can help to prepare workers for 21st-century jobs. I’m not a fan of the idea of a universal basic income, whether one presidential candidate’s proposal for $1,000 a month per household or something else. I’d much rather push for wage subsidies or an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit so that employers considering whether to replace workers with AI-enabled robots can be tilted in the direction of the workers, and where people get paid for working rather than for not working.

RSVP here to attend the October 3 “Authors Meet Critics” Panel