Christopher Carter, a PhD candidate in Political Science at UC Berkeley and a Research Associate at the Center on the Politics of Development, has been announced as a winner of the 2020 Best Fieldwork Prize from the Democracy and Autocracy Section of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The prize, which rewards dissertation students who conduct innovative and difficult fieldwork on the topics of democratization and/or the development and dynamics of democracy and authoritarianism, will be awarded at the virtual APSA meetings in September.

Carter’s research probes the causes and consequences of indigenous autonomy in the Americas in both historical and contemporary perspective. His work draws on over 16 months of fieldwork; close-range ethnographic research and natural experiments; more than 100 interviews with mayors, bureaucrats, and indigenous leaders; and a survey, lab-in-the-field, and conjoint experiments with a sample of over 300 indigenous community presidents.

The award committee praised “the extraordinarily breadth of the fieldwork” and noted that Carter’s ability “to collect data across highly divergent sociopolitical contexts is a testament to his creativity, adaptability, and commitment. We expect the fieldwork and the evidence culminating from it will make a valuable contribution to our understanding of indigenous governance and the literature on state-building and representation more broadly.”

We interviewed Carter to learn more about his fieldwork and dissertation.

How would you summarize your dissertation research project?

The dissertation project mainly looks at a puzzle around indigenous groups’ demands for greater autonomy. These groups have been politically and economically — and often socially and culturally — marginalized. To correct this, one option that governments have is to grant indigenous populations greater authority over their territory and to define the appropriate rules and regulations by which they will live. But what I found interesting is that a lot of individual native communities, when given the opportunity to have this autonomy, actually reject it. That’s pretty surprising, especially because most of the existing scholarship says that autonomy is the central demand of indigenous groups.

To understand why communities reject autonomy, I look at how previous experiences with extraction by both the state and private actors shape the decisions of indigenous communities to seek autonomy or not. These processes of rejecting autonomy began back in the 19th century and continue to the present day.

In addition to the puzzle around the rejection of autonomy, there are several other interesting puzzles that emerged in the research. First, that governments offer autonomy at all is surprising. We think of states as ignoring, assimilating, or even committing genocide against indigenous populations, especially in the historical period. The decision of central states to grant autonomy presents a surprising outcome and thus a puzzle that hasn’t been fully addressed in the existing literature.

I also looked at the long-term effects of autonomy arrangements when they are offered by states and accepted by indigenous communities. There are negative welfare effects that we might not expect, which has to do with the degree to which indigenous groups can achieve representation within the state if they choose the autonomy path. Autonomy may create fewer opportunities for indigenous communities to engage with the state or get resources from the state.

My dissertation looks at these various dynamics to understand otherwise unexplored costs of autonomy. It’s not a simple demand where all communities want it and will embrace it when offered. It is actually much more complex, with some important drawbacks.

How did you come to research this topic?

I grew up in western North Carolina, and from an early age, I was aware of certain issues around indigenous populations in the state, especially the Cherokee and Lumbee. However, I only began to truly understand the magnitude of the challenges faced by indigenous populations during the summer after my first year in college, when I volunteered in an indigenous community in Ecuador. It was through this experience that I was first exposed to a lot of the issues that have subsequently emerged in my dissertation. I became more aware of the degree of indigenous groups’ marginalization from the state and their alternative ideas around what governance is and should be. I became interested in when native groups achieve autonomy, and how effective it is in improving development outcomes once it is achieved. I then wrote my Master’s thesis at the University of Cambridge on indigenous-state relations in Ecuador.

In what geographic region were you primarily focused?

I conducted the majority of my fieldwork in Peru, where I traveled to indigenous communities, trying to better understand the issues they were facing. Specifically, what was most important for them? What were they getting (or not getting) from the government?

I conducted the majority of my fieldwork in Peru, where I traveled to indigenous communities, trying to better understand the issues they were facing. Specifically, what was most important for them? What were they getting (or not getting) from the government?

During this fieldwork, I spoke with many mayors and indigenous community leaders. I also did a survey of 300 indigenous community presidents to try to understand how they coordinate and cooperate to elect leaders to local government. I also did a survey of mayors in Peru and I spent a summer learning Quechua so that I could have more access to the communities, which are sometimes relatively closed to outsiders.

Coming in as an outsider in the Peruvian context presents certain difficulties, because it’s not the context in which I was raised. Cultures are different, policies are different, institutions are different. With indigenous communities, there are still different challenges. It is important to come in with an open mind and listen more than talk. That becomes fundamental. Speaking Quechua was extraordinarily helpful in gaining access to community leaders and showing that I was there to listen and understand and eventually try to tell the story that best reflects local realities. I feel that this approach led me to obtain more interesting information and insights than I would have otherwise. In addition to the fieldwork I conducted in rural Peru, I also conducted archival research in Peru, and in the United States and Bolivia.

My goal in this project was to author a systematic study that would give me the ability to make generalizations about social scientific phenomena. At the same time, I didn’t want to lose the important nuances and stories that distinguish individual indigenous communities from one another. To accomplish this, a variety of research methods — from interviews to surveys to participant observation —were necessary.

What were some of the key findings from your research?

Put simply, the decision of indigenous communities to reject autonomy depends on two main factors. The first is exposure to state extraction, or the degree to which states have taken indigenous land and labor in the past. These experiences generate skepticism among communities that reduces their faith in the state to respect autonomy and ultimately leads to a rejection of autonomy.

The second factor that determines community-level responses to autonomy is exposure to rural elite extraction, when large plantation owners or land developers attempt to seize native groups’ land or labor. Those experiences make communities more likely to pursue autonomy, because in those cases, autonomy reduces their susceptibility to elite extraction.

If indigenous communities experience both state extraction and rural elite extraction, they tend to reject autonomy. If they experience neither, they tend to reject, because of risk aversion. In other words, communities may say, if we haven’t experienced extraction, we don’t need autonomy, so we’re not going to take the risk of pursuing that path.

Functionally, then, communities are most likely to embrace autonomy when there’s private extraction, but not state extraction.

What are the implications if a group chooses autonomy, and why would they choose not to become autonomous, if they have that option?

The key negative outcome is that indigenous communities can lose access to state resources. Certain forms of autonomy may actually reduce indigenous communities’ ability to coordinate to elect leaders to state offices. This reduces native groups’ representation in government and therefore their access to resources.

Sometimes, the negative relationship between autonomy and access to state resources is more direct. Central states may say to communities, here is autonomy, but you will henceforth be responsible for collecting your own revenue. And even when these communities get money from the state, the infrastructure may not be there to deploy those funds. There are certain municipalities in Bolivia that have become autonomous that now want to revert back to their former status, precisely because there was no training given by the government on how to administer the massive amounts of money coming in, how to create projects, how to create bureaucracies, or how to create contracts with firms. And some rural areas don’t have the building and construction firms to hire for projects like bridges and roads.

Do you feel this plays out the same way in different parts of the world, for example, in the U.S. or Africa? Does it vary by geography?

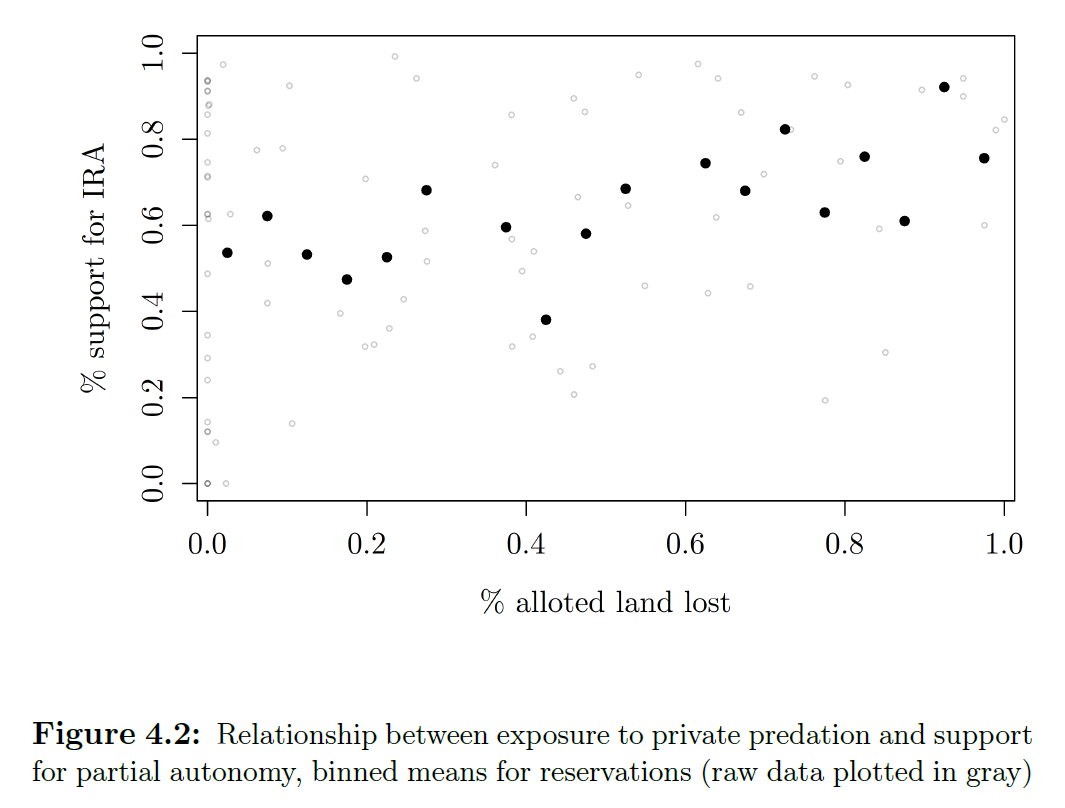

I think it does hold in different regions. In my dissertation, I look at Peru centrally, but I also have chapters on Bolivia and the United States, and other data from various countries in the Americas. In the United States, there was an autonomy extension in 1934 called the Indian Reorganization Act that was passed under the Roosevelt administration, which was labeled the Indian New Deal. This law aimed to give indigenous groups more political autonomy over their communities and their reservations. Almost two-thirds of tribes accepted the Indian Reorganization Act, but a third of them rejected it. So one part of my dissertation looks at why different reservations made the choices they did.

What I found is that exposure to elite extraction under the Dawes Act — the period that preceded the Indian Reorganization Act, in which indigenous groups lost substantial land to private land developers — actually increased the likelihood that reservations would embrace autonomy. That’s consistent with the theory. Other evidence I collected suggests that those reservations that were exposed to state extraction, particularly the Navajo — who lost much of their livestock through a livestock reduction program that the Roosevelt administration implemented — were less likely to accept the Indian Reorganization Act. If you go through the minutes of their meeting to decide whether or not to embrace this Act, you see that the Navajo were really cognizant of this idea that you could not separate the livestock reduction plan from the Indian Reorganization Act. If the government was not credible in one domain, they were also not credible in another domain.

In addition to historical cases, the theory also applies to certain contemporary cases. In Bolivia, the decision to resist autonomy often occurs precisely because groups have different experiences with extraction. As I show in the dissertation, those communities that experience elite extraction are more likely to embrace autonomy, but communities that experience both state-led and elite extraction are more likely to resist it.

What lessons might policymakers at different levels take from this? What are the key takeaways?

We can think of two poles of government policy: autonomy or integration. My research and conversations with indigenous groups suggest that the best policy would balance between these two poles by granting indigenous communities autonomy at a very local level, while also increasing their formal guarantees of representation within the state, such as quotas for political office.

We can think of two poles of government policy: autonomy or integration. My research and conversations with indigenous groups suggest that the best policy would balance between these two poles by granting indigenous communities autonomy at a very local level, while also increasing their formal guarantees of representation within the state, such as quotas for political office.

I think that would reduce the costs of autonomy: indigenous institutions are preserved and legitimized, and groups still have guaranteed access to state resources.

What was different about your fieldwork from how other researchers might have approached this?

One of the things that a lot of researchers have done with indigenous politics, which is extraordinarily valuable, is to examine the effect of national-level indigenous organizations and movements in shaping public policy. National organizations are incredibly important, but there are also really important community-level factors that shape political and development outcomes. I wanted to draw attention to those dynamics.

For example, “indigenous” is an overarching term that masks extraordinary variation in the diversity of indigenous groups. I’ve seen communities that live within 10 miles of each other that are completely different from one another. They speak different languages, they have different cultures, they have different customs. There’s seemingly little that unites them, except perhaps an overarching indigenous identity. And in most cases, that’s not really the identity that’s most salient for them. So I wanted to dig into that more in trying to understand that local-level variation in what indigenous groups want and what struggles they’re facing. What are the important things that are of concern to them, and how do they respond? Do they really want the policies that are being lobbied for and negotiated at the national level by indigenous organizations and movements?

To do all that, it becomes important to visit communities and talk to their members and leaders. There are 6,000 indigenous communities in Peru alone, so I was able to visit only a handful of those. Surveys become valuable tools to try to understand the bigger picture, aside from the important, but not necessarily generalizable picture I got from visits to individual communities.

What are the implications of this research more broadly for political science, or for other disciplines?

Political scientists generally assume that central states want to monopolize force or control over their territory. The idea that states cede autonomy to native groups, which have been politically and economically marginalized throughout history, is sort of surprising.

Furthermore, indigenous groups were often ignored, displaced, and even killed by governments, particularly during the colonial and immediate post-colonial periods. Indigenous groups lacked citizenship rights, even in the U.S. and Canada, until the 20th century. The idea that native groups were able to lobby for autonomy in 19th-century Guatemala, Bolivia, and El Salvador is impressive and surprising. It causes one to rethink what the central state was trying to do in an early period of state building and state formation.

The decision by central states to recognize autonomy depended on two factors. The first is that indigenous groups needed to be an important part of the coalition of the incumbent president. Second, if rural elites were strong enough, they could veto any extensions of autonomy, which they opposed, even if the central state wanted to extend autonomy. So you needed two conditions: indigenous groups had to be an important strategic ally of the incumbent to provide the incentive to meet the indigenous demand for autonomy. And rural elites had to be sufficiently weak that they couldn’t block the emergence of autonomy.

Images:

- Banner image: Communal labor project in indigenous community, Cusco, Peru.

- First image: Christopher Carter, PhD (UC Berkeley, 2020)

- Second image: Indigenous community in Cusco, Peru with sign noting formal registration with Peruvian government.

- Third image: Bivariate relationship between exposure to rural elite extraction and support for political autonomy (1930s United States).