How can we track online extremism through political advertisements? Using data from online advertising, Laura Jakli, a 2020 PhD graduate from UC Berkeley’s Department of Political Science, studies political extremism, destigmatization, and radicalization, focusing on the role of popularity cues in online media. She is currently working on her book project, Engineering Extremism.

She is currently a Junior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Starting in 2023, she will be an Assistant Professor at Harvard Business School’s Business, Government and the International Economy (BGIE) unit. From 2018 to 2020, she was a predoctoral research fellow at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, and at the Program on Democracy and the Internet.

Social Science Matrix content curator Julia Sizek interviewed Jakli about her work, with questions based on political advertisements and graphics from Jakli’s research.

Your research uses the Facebook Ad Library to understand far-right political parties. What insights do advertisements provide for understanding far-right parties?

Since 2018, the Facebook Ad Library (also known as the Ad Archive) has publicly documented the political advertisements hosted on the platform, as well as some limited metadata for each ad (for example, the name of the ad buyer, the number of ad impressions, total ad expenditure, geographic target, and audience gender and age demographics). Initially, the Ad Library exclusively featured ads run in the United States, but it expanded to dozens of other countries within a year. Since I study European politics, this expansion of the Ad Library opened up a new way to explore party messaging at scale.

Much of my research considers the gap between the publicly stated and privately held beliefs and preferences of far-right voters (and party elites themselves). In line with this, I was interested in examining party ads because the far right may be incentivized to present a more mainstream right-wing ideological profile in formal documents and in mass media campaigns to appeal to a broad audience. Meanwhile, when the far-right is targeting a narrow, custom audience through online media, the party may use more extreme campaign content. This is because, with digital micro-campaigns, they do not have the same political incentive to appeal to the masses or signal ideological common ground with center-right parties.

With my current political ads research, the objective is to better understand far-right party strategy and political positions. The main advantage of ads in this regard is that most parties field hundreds of unique online ads in the months leading up to an election. The sheer volume of political ad text available means that it is quite feasible to construct reliable ideological profiles for small parties, and to create valid inferences about party strategy. Moreover, since online ads are time-stamped and geographically targeted, they can be used to trace how positions change over time, both sub- and cross-nationally.

How do political ads work on Facebook? Who buys them, and how are political ad purchases split between groups? In other words, who is posting these ads, and how do they find their audiences?

Many party ads are purchased by the national party itself, meaning that they are sponsored by the party’s main Facebook page, even if the ad content is focused on a specific regional or candidate campaign. But it can be a more decentralized process, and each political party can choose to run its political campaign through a combination of national and local advertising. In some European countries, I see party candidates and local party organizations paying for and running their own ads.

Facebook allows advertisers to target not just by age, gender, and geographic location, but also by political interests and hobbies. Email lists gathered through rallies, fundraisers, and other events can be used to target customized political audiences. Moreover, these inputs can be used to find “Lookalike Audiences” that share interests, traits, and demographics with the established email list. These advertising parameters allow campaigns to target political ads quite narrowly and precisely.

One weakness of the Ad Archive is that it doesn’t actually reveal how the campaigns found their audiences. All you have available as metadata is basic demographic information, including a breakdown of the audience by gender, age, and geographic location. You can make some inferences about whom parties targeted based on this information, but the ad algorithm may also be impacting that audience.

For example, you can’t distinguish between when the party directed ads to be delivered to males between the ages of 18-24, or when the ad algorithm picked up on the fact that men between 18-24 interacted with the ad at higher rates, and therefore “learned” to deliver more ads to this segment over time. In other words, the audience is curated both through what ad buyers specify as their parameters (e.g., let’s target XYZ demographics), and the algorithm independently determining who would be an efficient target to display the ad.

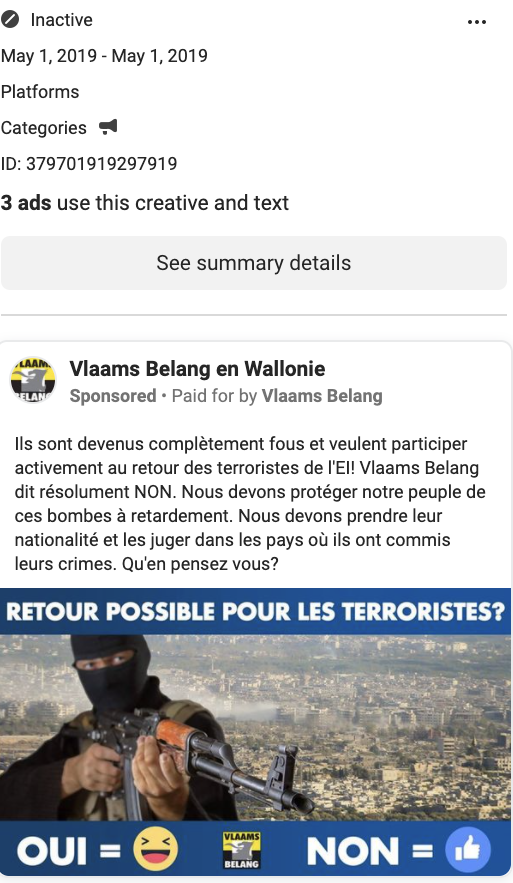

This advertisement (Figure 1) from Vlaams Belang, a far-right party in Belgium, is fascinating because of the way that it is designed to track viewer reactions. How are advertisements on social media different from ordinary advertisements, and are you able to track how people interact with these advertisements?

The ability to rapidly field and test the performance of different political ads is one aspect of online advertising that distinguishes it from older forms of campaigning. Parties don’t have to commit to one message or thematic policy focus through a campaign season. This flexible, feedback-based approach is precisely demonstrated in this ad from Vlaams Belang. It asks ad viewers to signal using the laugh emoji if they agree with the return of foreign terrorist fighters (known as “returnees”) and “like” if they disagree with the policy. Presumably, the idea is to quickly and cheaply test how salient this issue is for potential voters.

Researchers are not easily able to track how people interact with these advertisements unless the advertisement links to a post on a public Facebook page. But in the case of Vlaams Belang and most parties that do these quick polls through ads, the poll takes you to a party webpage so they can get more information about their audience (and possibly elicit donations). One other way to get a sense of how people interact is simply through the number of impressions the ad gets. Impressions count the total number of times the ad is displayed on viewers’ screens. This is broadly informative, but doesn’t mean that audiences are actually clicking on the ad or interacting with its content in any way, so the inferences researchers can draw are quite limited.

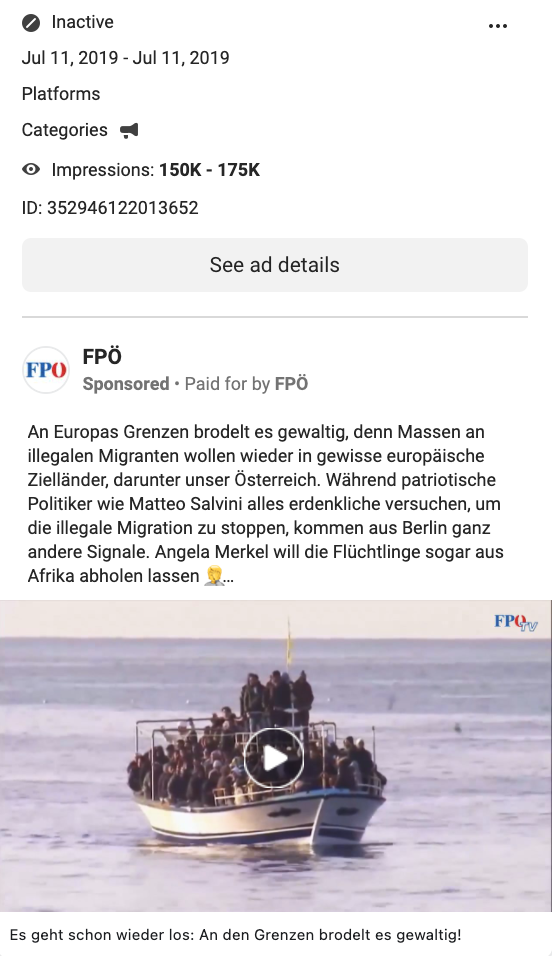

One of the benefits of online advertisements, in contrast to traditional advertising, is the ability to target certain groups. This ad (Figure 2) shows an ad that targeted audiences specifically in Austria. How did you find that targeted advertising worked for far-right groups, and how did advertisements differ at the local and national scales?

Broadly speaking, the demographic metadata suggests that the far right has a much higher ratio of male ad audiences than do other parties, which makes sense, given the male skew of their voter base. But there is such limited metadata provided by the Facebook Ad Library that I have not been able to establish any other notable demographic trends. I am currently working on understanding the geospatial trends of far-right advertising but cannot say anything definitive yet.

I will say that the more localized advertisements — typically fielded by regional party organizations or local candidates — differ substantially in content from national ads. The more localized campaign material is crafted to resonate with local news events and community issues. Far-right political ads that target a narrow geography appeal to voters less on abstract political platforms or ideological principles and more on tangible and immediate localized concerns. In effect, this represents a shift to digital “home style” politics, by which the far right frames their platforms such that constituents of each district are led to believe party representatives are “one of them” and have their immediate interests in mind when crafting policy.

In my qualitative analysis, I found that regional far-right party branches often stylize themselves as accessible, populist, and anti-political, presenting their party as concerned with what is “happening on the ground” and what the “people” really want. Relatedly, these online campaigns are crafted and fielded rapidly, in a manner that is less professional, less polished, and more casual than offline campaigns. Knife crime is one example of a localized thematic focus common in far-right ads (see Figure 3).

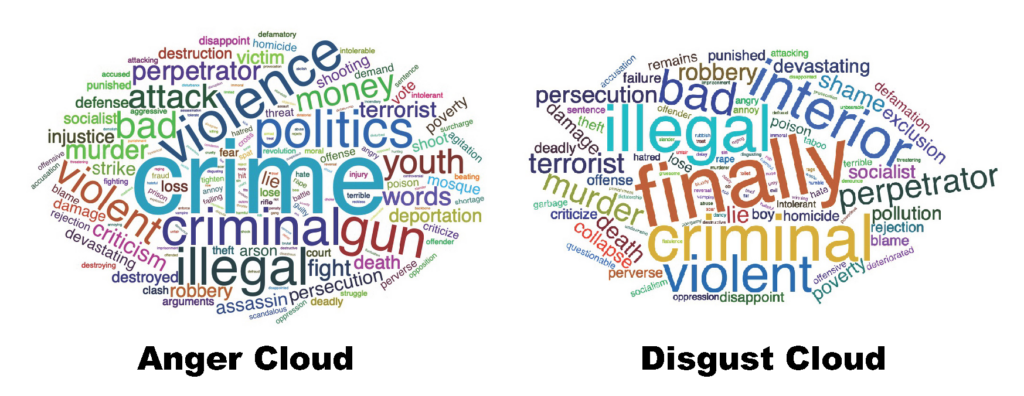

Working from a large dataset of far-right political ads, you translated the advertisements into English, and then used the NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon to identify how the ads evoke emotions like fear, disgust, and anger. These images (Figure 4) show word clouds based on advertisements from the German AfD (Alternative for Germany) party. What do these word clouds show?

First, I want to note that the share of negative emotive ad content is typically much higher in far-right ads than in the ads of other parties. Their negative ad campaigns focus on — and often exaggerate — social and economic problems, while identifying other people, parties, and institutions as responsible for them. Consistent with much of the literature, I also found that the far right is associated with specific emotive appeals, most prominently with fear and disgust, but also with a higher share of anger emotion words, on average.

Using the NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon, the disgust word cloud visualizes the terms tagged in the far-right AfD’s (Alternative for Germany) ads as being words associated with disgust. The size of the term in the word cloud helps visualize its relative frequency in appearance across the ads. The anger word cloud visualizes the same, but for anger-associated terms in the ads. These figures show that illegality, criminality, and violence are some of the most prevalent disgust-associated themes found in German far-right ads. There is quite a bit of overlap here with the most frequently found anger-associated words. Themes of criminality, violence, and terror attacks are frequently discussed by AfD, presumably with the intent of evoking anger toward the political status quo.

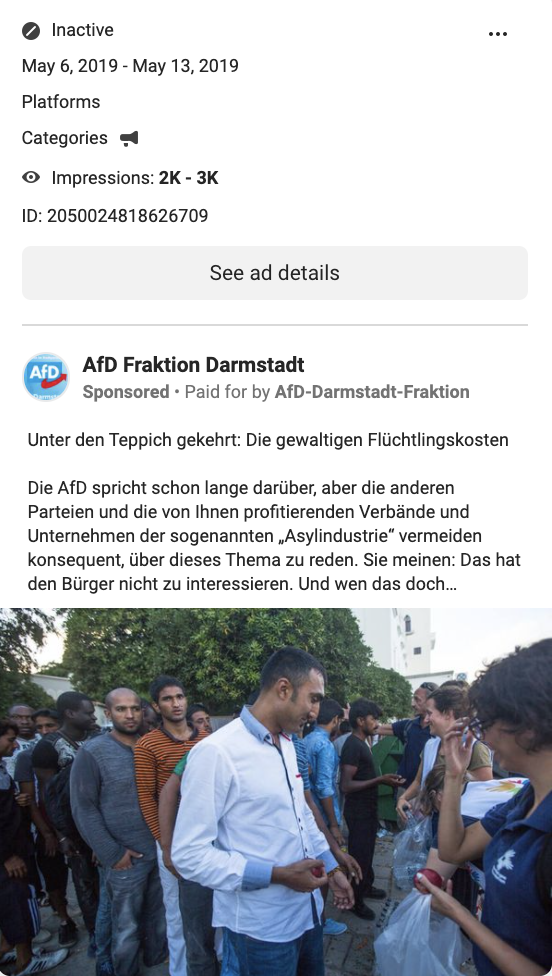

One of your findings is that far-right groups in Europe tend to claim ownership over the topic of immigration, as is reflected in this advertisement (Figure 5). How did you measure the focus on immigration among far-right parties in comparison to their more moderate counterparts?

I use a method called structural topic modeling to determine whether the far right maintains issue ownership on immigration. In topic modeling, each document (in this case, party ad corpus) is modeled as a mixture of multiple topics. Topical prevalence measures how much each topic contributes to a document. Put simply, I use metadata on which party fielded each ad text to examine differences in topical prevalence across the ad texts, and sort topical prevalence by party family. I estimated the mean difference in topic proportions for far-right parties and all other parties to determine which topics are more prevalent in far-right ads.

I use this to gauge whether there is disproportionate emphasis on immigration in far-right campaign ads, or whether immigration topics are prevalent across different types of parties. In a large majority of sampled EU countries, I found a disproportionate emphasis on immigration issues on the far right, which is consistent with issue ownership. There are three notable patterns in how the far right discusses the immigration issue across Europe. First, many parties specifically emphasize Muslim migration and frame Islam as a unique threat to national values and cultural identity. Second, immigration is often tied to criminality as well as to issues of women’s safety. Third, it is linked to general Euroscepticism and the EU’s multiculturalism.

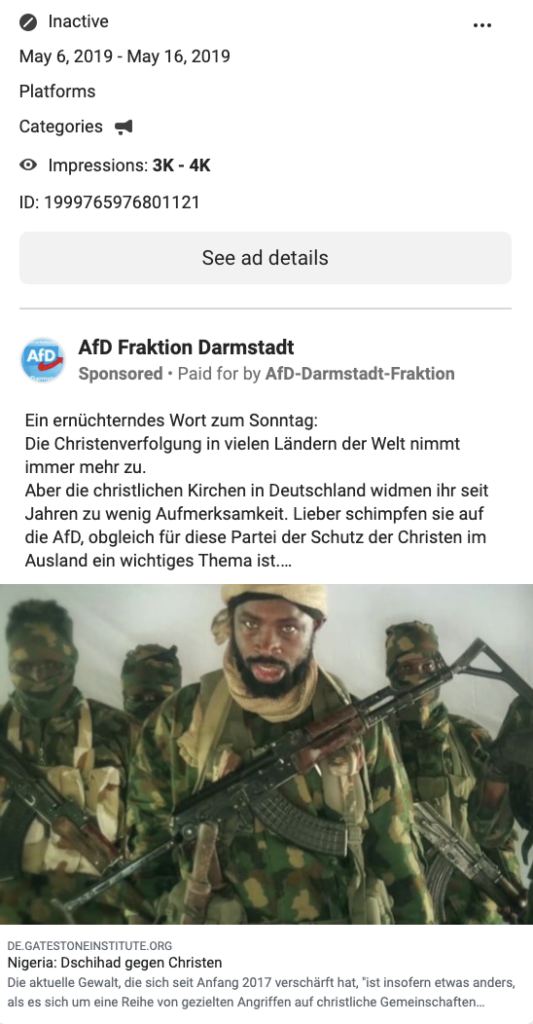

While your analysis focused on the text of far-right political advertisements, the images would seem to be an essential part of ads’ effectiveness, as we can see in this image (Figure 6). What do you think are the limits of a text-based analysis, and what are avenues for investigating visual complements to your text-based research?

It is definitely an important limitation. Many ads also have videos embedded, not just images. By reducing the current study to text analysis, I may miss the fundamental features that lead viewers to interact with the ad, click on related content, or mobilize for the party.

More broadly, there seems to be a trend in recent years of decreasing emphasis on text and increasing emphasis on visuals and videos in political ads. These trends mirror other social media trends (e.g., the rise of TikTok and YouTube). I think the political parties that acknowledge this trend and craft their online ads accordingly have a leg up over those that do not.

Based on a small qualitative assessment of these ad visuals, what I can say is that the inflammatory, emotive content I try to capture through text comes through much more explicitly in images and video. My sense is that the visuals associated with far-right ads are quite striking and substantively different from the ad visuals of other parties, although I have not tried to quantify these differences systematically. As our tools for image and video analysis improve in social science, I hope to study these features more rigorously.