In this interview, Aidan Lee, a PhD student in the UC Berkeley Department of History and a 2022-2023 Matrix Communications Scholar, interviewed Margaret Crawford (shown above), Director of Urban Design, Professor of Architecture and Urban Design in the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design.

Professor Crawford holds degrees in architectural history, housing, and urban planning. Before coming to Berkeley, Crawford chaired the History, Theory, and Humanities Program at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles and, from 2000–2009, was professor of urban design and planning theory at the Harvard GSD, teaching history and design workshops and studios. Her scholarly work includes Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The History of American Company Towns, The Car and the City: The Automobile, the Built Environment and Daily Urban Life, and two editions of Everyday Urbanism, along with numerous articles and book chapters on immigrant spatial practices, shopping malls, public space, and other issues in the American built environment. In 2008, Doug Kelbaugh called Everyday Urbanism “one of the three leading paradigms today in urban design.” Since 2003, Crawford has been investigating the effects of rapid physical and social changes on villages in China’s Pearl River Delta. She recently co-edited Critical Texts in Chinese Urbanization, a four- volume collection of English-language studies of Chinese urban development. She is currently working on regional design projects in the Salinas Valley.

A defining feature of the state of California has been its diverse ethnic makeup. For many California residents, the images in this interview may appear to be mundane features of a daily commute or routine: 99 Ranch Market is a familiar landmark in many a Californian suburb, and Boba tea cafes have become mainstream. But by situating California’s ethnic suburbs in historical context, this interview seeks to bring to light the contingent factors that led to the rise (and characteristic shape) of the “ethnoburbs,” and why they are now permanent features of America’s built landscape.

This interview draws from Professor Crawford’s chapter, “The Fung Bros Rep the Ethnoburb,” in Van Damme et al eds. Creativity from Suburban Nowheres: Rethinking Cultural and Creative Practices(University of Toronto Press, 2023), as well as her recent presentation, “The Rise and Fall of the Mini-Mall,” given at the Society of Architectural Historians 76th Annual International Conference in Montreal, April 13, 2023.

(Please note that the interview was lightly edited).

Aidan Lee: The first image featured here depicts the Asian supermarket chain 99 Ranch, a staple institution of what you refer to as the “ethnoburb” in your research on Asian American communities in the San Gabriel Valley. Can you describe the “ethnoburb” and say more about the methods that inform your research?

I’m in the field of built environment studies, which encompasses the entire built environment in the world. It draws from architectural history and urban history, combining both. My particular approach involves reading the built environment and exploring significant issues through ordinary things. I examine how people live and adapt in their built environments, and what the built environments mean for their own daily practices. I examine completely ordinary aspects of everyday life, seemingly mundane issues that shape people’s lives in ordinary ways.

It’s great that you start off with this picture of the 99 Ranch supermarket, because that’s the kind of everyday environment that interests me. In fact, in my work on the San Gabriel Valley, the supermarket plays an important role. I feel that looking deeply at very ordinary places and practices can tell you a lot about much more serious and important issues. Towns with a 99 Ranch supermarket, for example, have in recent years functioned as hubs that attract Asian immigrants from neighboring communities that have traditionally been less diverse, suggesting that the establishment of ethnic retail centers is not just a symptom of broader demographic changes in the San Gabriel Valley, but also a catalyst for further change.

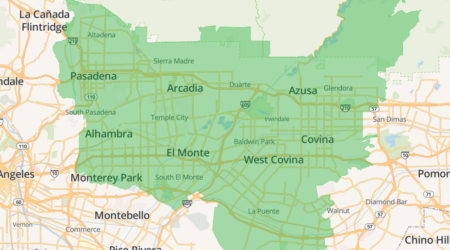

The largest ethnoburb in the US is in the San Gabriel Valley, which is east of downtown Los Angeles. There are around 11 suburban towns in the greater Los Angeles area that have Asian majorities, so this is a very new condition. These are not Chinatowns, which were created through a process of exclusion. Ethnoburbs are places that immigrants have voluntarily and very positively chosen to live in. For example, Fred Hsieh, a local real estate agent, started advertising Monterey Park as the “Chinese Beverly Hills” to buyers from Hong Kong and Taiwan, though it’s actually more middle-class than upper-class.

The ethnoburbs are mostly Californian; the only other state where you can really find something similar (but not identical, and on a smaller scale) is New Jersey. In the decades after World War II, geopolitical and economic issues drove a lot of immigration from Hong Kong and Taiwan to California. A particularly important factor in the rise of the Californian ethnoburbs was the 1965 Immigration Act, which opened the doors to many different groups of people who had not been coming before. The act privileged those with higher education, so you saw a lot of well-educated people, especially from Taiwan, immigrating to the US during this period. Many of them started to settle in Monterey Park and eventually crossed over to all other suburban towns nearby, creating these massive Asian suburbs.

Often in the literature, ethnoburbs are just referred to in a generic way – simply as “Chinese,” for example. But in fact, their populations show a broad range across the economic spectrum, from San Marino, the most expensive and wealthy town in the entire Los Angeles County, to El Monte, which is one of the poorest cities in the county. So it’s a very complex demographic, ethnic, and economic geography. And of course, none of these towns is 100 percent Asian. There are complicated mixtures with other ethnic groups. For example, in San Marino, you basically have Chinese and white. In El Monte, you have a lot of Latinos, Vietnamese, and Chinese, but very few white people. So every town has a unique mixture of different groups; it is not a unitary phenomenon, but actually quite complex.

Considering where many of these migrants come from (e.g., Taiwan, Hong Kong, southern China), it seems like a very urban population that is moving into the suburbs. Can you see unique patterns of urban life (including structures or local institutions) in these ethnoburbs?

No, I would say that this place remains resolutely suburban, and that almost all of these immigrants ended up living the car-oriented suburban lifestyle in single-family houses or small apartment buildings, shopping in strip malls. But while the suburban form is the same, the content is dramatically changed. The content of the mini malls is very Asian: for example, you will see a huge number of all kinds of Asian restaurants. On Valley Boulevard in San Gabriel, there are something like 300 restaurants. It has really become the center of Chinese food in the United States. Queens, New York might be a competitor, but most people would say that if you want really good Chinese food, Valley Boulevard is the place to go. It’s been featured in a lot of food magazines, because there is an incredible breadth of Asian food, but you can also find everything Asian there. So, if you move to the San Gabriel Valley and only speak Cantonese, you will not have any problems. But you’re still going to have to live a different lifestyle. I think that has been difficult for many, especially for the elderly population. People often move as multi-generational families, so the seniors have a hard time because they don’t drive. This is a very spread out, totally car-dependent society with very little public transportation. And so this is one of the issues that urban planners have to deal with. Recently city planners have proposed funding paratransit vans and similar solutions to allow seniors to have more mobility.

This is a map of the 626 area code, the San Gabriel Valley (SGV). Your research explores depictions of everyday life in this area, especially through the work of the YouTube comedian-musician duo, the Fung Brothers.

There are a lot of differences among the first-generation immigrants. The earliest immigrants from Hong Kong and Taiwan, for example, don’t even speak the same dialect. And then when mainland Chinese started moving in, a whole other set of (social and political) conflicts emerged. But all that vanished in the second generation, which essentially became Asian American. There are a host of stereotypes about Asian American kids, according to which they are supposed to be very nerdy and studious, get good grades, be well behaved, and do what their parents want. In other words, kind of boring. And so that has been the predominant stereotype. But in reality (and as has been seen through the Fung Brothers’ work), there is an incredibly dynamic teenage and youth lifestyle in the SGV. For example, many kids go to different boba tea cafes in the evenings and on weekends. These cafes offer a variety of games and other activities, and people hang out there for hours. This kind of thing has become an identifier that young SGV natives like the Fung Bros recognize.

Another feature of SGV identity involves an overwhelming interest in Asian food. Given all the variety of Asian restaurants, I think we can say that they’re not these typical teenagers going to fast food restaurants like McDonald’s. They’re actually really indulging in Asian food. And part of the reason that there are so many Asian restaurants is because young people are patronizing them. Obviously, they get a lot of information and ideas about food from their parents, so that became one of the strongest markers of Asian American identity. The Fung Brothers encapsulated this new kind of SGV, 626 identity in their videos, and they became super popular, reaching a million YouTube subscribers very quickly. And so that helped to create a very distinctive Southern California, Asian American identity.

I also think the Fung Brothers understood the nuances of the built environment. In their video, they talk about these long boulevards that exist in Southern California, and how each one has a distinctive identity. They list the neighborhoods from south to north from the working-class areas to the most elite, and talk about the kind of different permutations of Asians in each of these places. I think this 3-minute video tells us a lot about what life in the San Gabriel Valley is like, and almost represents a kind of sociological analysis in its detailed breakdown of different regional populations.

One urban feature that appears frequently in the Fung Brothers’ music videos is the “mini mall.” Could you outline the history of the mini malls? What is the connection between the mini mall and the ethnoburb? Who first developed these spaces and what were they used for?

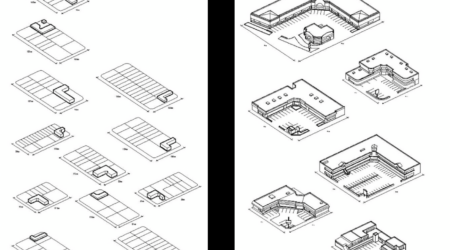

The interesting thing about the mini mall is that it also emerged at the confluence of two geopolitical issues. One was the 1970s gas crisis, which began when OPEC countries started boycotting any country that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. This was the beginning of the energy crisis, which we’re still dealing with today. The energy crisis, and the economic crisis that happened alongside it, led to a lot of gas stations going out of business, leaving empty gas station sites. Los Angeles has always been a car-centric city, so there were way more gas stations than in most places. Low-end developers noticed this condition, and they started buying up these corner sites. The lots were small, leading them to unwittingly create the typology of the mini mall, which is a simple L shaped corner, a one-story (sometimes two-story) shopping center with parking in front. They built them as cheaply as possible. There were no regulations or zoning issues because they were already commercial sites. After they started, oil companies contacted developers when they had lots to sell. So over the course of only 20 years, Los Angeles saw the development of 3000 mini malls.

What kinds of businesses moved into these mini malls? The 1965 Immigration Act opened doors for a lot of immigrants, and many of them came to Los Angeles. Los Angeles was the new Ellis Island, a major magnet for immigrants. A lot of immigrants had language problems. They didn’t have work histories in the U.S., so they became entrepreneurs, starting small businesses. In fact, even today, 50 percent of small businesses in Los Angeles are owned by people who were not born in this country. So there was a huge boom in immigrant businesses located in the cheap space of the mini mall. And a lot of developers worked with them to build their businesses and tried to better understand immigrants and their neighborhoods. They encouraged successful businesses to become chains and locate themselves in the other mini malls that they were building. The building of mini malls thus became a very immigrant-driven process. And in fact, I think everyone who lives in Los Angeles now knows that if you want a good ethnic restaurant, you will find it in a mini mall.

And did these real estate developers often come from a similar ethnic background as the mini mall small business owners?

Not at all. I think they just saw a good business opportunity. In Los Angeles during the 1970s, 1980s, and even 1990s, there was a lot of conflict about the city’s identity. David Rieff wrote a book titled Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World. The crisis was rooted in Los Angeles becoming a “majority minority” city. And I think that the speed with which these different ethnic groups began setting up their businesses in LA’s mini malls (with their non-English signage) really unsettled the traditional urban elites and older residents of these areas.

Was there any movement back, in the sense that too many malls were built and had to be converted back into gas stations? Or did mini malls become a permanent mark on the suburban landscape?

The number of gas stations has continued to decrease. Real estate developers favor the “highest and best use” for any site, so most of these properties could never go back to being gas stations, which bring less revenue and accommodate fewer businesses. But again, mini mall sites are small, and they’re still making money for the people who own them and the people who have stores there. So they are not being redeveloped as much as you might think. They’re still, I would say, successful.

Of course, there was pushback from local communities and planners from the very beginning, when mini malls were considered to be one of the most degraded kinds of buildings in the city. Urban planners, architects, and city officials all tried to stop them unsuccessfully through regulation. Finally, economic forces slowed down mini mall construction, although in the eastern San Gabriel Valley, which still qualifies as an “ethnoburb,” they are still being developed.

Can you say more about the critics of the mini malls? What were the kinds of architectural or planning standards that they subscribed to?

It’s interesting. The American Institute of Architects (AIA), a professional organization, was a major critic, although almost every mini mall development had an architect involved with it. In the 1980s and 1990s, even architecture critics for the LA Times argued that a number of mini malls were well-designed

From the beginning, there were many criticisms, but a major one was simply that these were cheap, low-end buildings. Critics talked about curb cuts (depressed curbs which allow for pedestrian and vehicle access), which were seen as visually offensive and potential causes of flooding. But certainly the gas stations had just as many, if not more, curb cuts. There was either too much parking or too little parking. Basically, though, the criticisms were aesthetic. Critics just thought mini malls were ugly, a crime ambiguously referred to as “visual blight,” which is obviously a subjective interpretation. Although, if you look back at what was there before, it’s hard to maintain that criticism because certainly gas stations were much more unsightly.

But also, around this time, there was a change in urban perceptions about Los Angeles, particularly after the 1992 social unrest. Many people wanted to reconceptualize Los Angeles to be more like other cities. Instead of thinking of the city as a car-dependent, sprawling place, they envisioned LA as a more urbane environment that had buildings coming right up to the sidewalk. Obviously, mini malls are the exact opposite of this ideal. One way the mini-mall exemplifies this is the empty corner, which goes against conventional urban design principles, which emphasize building up corners. The mini mall is also set back from the street by its parking lot. This destroys any possibility of creating a “street wall,” where the front of the building comes straight down to the sidewalk, as is typical in Manhattan and most European cities. Thus the mini-mall became a symbol of the car-centric city that needed to be eliminated.

Professional architects and planners did not like the malls, and neither did citizens. In 1989, roughly 10 percent of respondents to a quality-of-life poll conducted by the Los Angeles Times cited mini malls as their biggest pet peeve. I think this also had to do with the number of immigrant businesses in the San Gabriel Valley. As recently as 2013, the town of Monterey Park even attempted to ban retail signs that did not have an English translation, a throwback to 1980s city regulations that required English signage. Much of this had to do with the alarm that these massive demographic changes had created among prior residents, especially people who were involved in city governments in the greater LA region. The mini malls did not align with the image that they wanted for their city, but now this may have changed.

Today, there are a huge number of people who love mini malls and who celebrate Los Angeles’ extreme diversity. But that took a long time to achieve. There was a lot of struggle over the image of the city: was it going to be the capital of the Third World? Or was it going to be a much more traditional city? The city actually has since developed better public transportation, including a subway system and light rail; in some ways, it has actually become more like a “typical” or desirable city. At the same time, the diversity of its residents has become one of LA’s biggest assets.

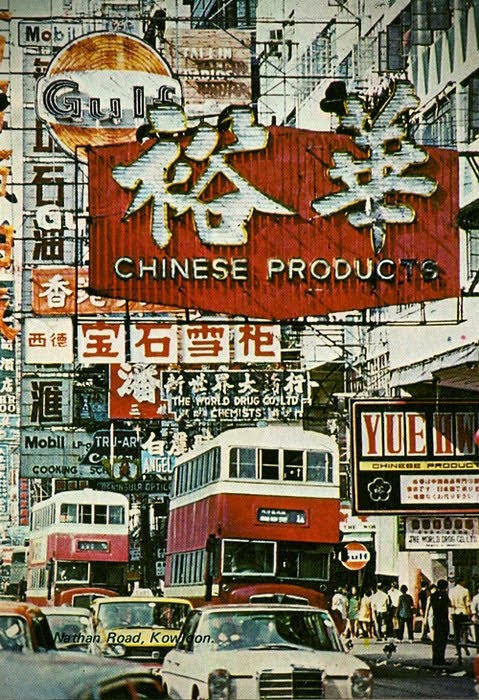

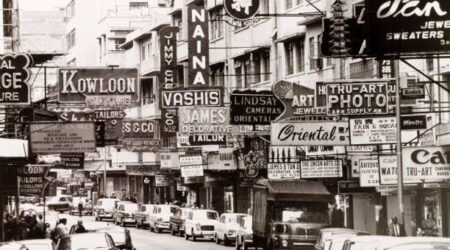

“Visual blight” is also interesting because it is a global phenomenon. In East Asian cities like Taipei, there are similar debates about street signs, for example, which over the past couple of decades have become far more standardized and regulated. Some of your research has touched on East Asian built environments, specifically in southern China. Can we see similar concerns in urbanizing regions there, in terms of the aesthetic and functional criticisms of urban space?

Definitely. In Taipei, Hong Kong, and Guangzhou, for example, there is definitely a policing of the built environment away from the extremely lively visual assault that formerly characterized Asian cities. In Hong Kong, when you look at pictures from the 1960s, the signs protrude into the street. It’s an incredibly vivid and colorful environment. And now when you look, it’s much more controlled. This is the constant struggle of urban planners, who use planning restrictions and planning codes to control the city, because somehow visual blight is seen as, I believe, a symptom of political, cultural, and social confusion. There is an idea that if you have a coherent built environment, it means you have a coherent society, even though that is absolutely not true. In addition, the globalization of building types (such as shopping malls), development practices, and architectural design has produced a more generic urban landscape.

But certainly, the debates over visual blight are really a struggle over taste, a struggle that is happening everywhere. Who determines taste? Often, the coherence of the European built environment has been the role model everywhere. And so, in almost every city, including the city I live in, Berkeley, there are planners who undertake streetscape projects where they convince store owners to paint their buildings a uniform gray, then place restrictions on the size of the signs. You see it everywhere because it is intended to create a “tasteful” or, let’s face it, upper middle-class environment.

Ultimately, the control over things like visual blight is really about people with power trying to exert control over urban space, but also constantly being threatened by new forms of urban vitality or informality that come up. In Singapore, for example, street vendors were relocated into hawker centers (these are contained, often indoor, spaces that facilitate better regulation). While the food is still great, the relocation is really a form of control, and obviously the impetus is rooted in images of what constitutes a “developed city” or a “developed country.” So, when mini mall critics saw non-English signage in LA, they thought it looked like the city was going “backwards,” or turning into the “capital of the Third World.” To some extent, this kind of urban cleansing is a perennial concern and a continuous process in urban planning as a discipline. I would argue that, in fact, this is the very history of urban planning.

What are some of the emerging trends in the present-day ethnoburbs, whether broad demographic shifts or new urban planning policies? Are you noticing certain patterns that are emerging today that are really distinct from the pre-Covid years?

Physically, the San Gabriel Valley has been migrating East. And in a way, some of the issues and struggles that went on in the past are now going on in the eastern part of the San Gabriel Valley, in places like Diamond Bar and Hacienda Heights. Many new Chinese restaurants are located there, so it is becoming a new epicenter. There are a few interesting dynamics at work in this growing region. Typically, wealthier people will move to the eastern part of the San Gabriel Valley, which has larger houses on bigger lots. Urban historian James Zarsadiaz has written an excellent book on this topic called Resisting Change in Suburbia, in which he discusses how Asian immigrants, especially Chinese immigrants, have bought into very American frontier imagery when they buy houses there. Demographically speaking, there’s been an interesting phenomenon of Chinese immigrants moving into expansive suburban regions that are traditionally less diverse, and yet they are still able to make a short and easy trip to a neighboring town to shop at ethnic supermarkets like 99 Ranch.

The conclusion from my investigation of the San Gabriel Valley is that generally this demographic shift (the growth of the Asian population) has concluded in a peaceful way. After an initial period of strong resistance, currently there is very little social tension. I conducted interviews with white, Latino, and Asian residents, and found very few of the kinds of social struggles that you might expect. For example, going back to supermarkets, in San Gabriel, there are no American supermarkets anymore. There are only Asian supermarkets. Yet non-Asian residents I spoke to are not resentful about some sort of perceived loss. One of the reasons for this may be the car-centric nature of the San Gabriel Valley. If you don’t have a Ralphs or Vons supermarket near you, you can just drive five or ten minutes to the next town and find one. You are not confined to your immediate neighborhood.

This is true not only for groceries, but for other essential services. When I interviewed a white student here at Berkeley who was from the SGV, I learned that she commuted by car to La Cañada each day to go to school, a common experience for many young people in the Los Angeles area: high schools, both public and private, are located all over the region. That is also one way in which some people bypass the problem of overly competitive high schools (with predominantly Asian student bodies). In other regions, such as Fremont in the Bay Area, this situation has contributed to substantial white flight from otherwise very desirable neighborhoods, as Willow Lung-Amam has shown. (See chapter 2 in Lung-Amam’s book, Trespassers: Asian Americans and the Battle for Suburbia, for more detail on the school situation in Fremont.) Many families felt that their kids just could not compete academically with the students of Asian ethnic background in their neighborhood. To some extent, that phenomenon is visible at the University of California, which has a predominantly Asian undergraduate student body. Moving away, however, is not a viable option for many families, especially those that have been living in San Gabriel for multiple generations. so, in a way, driving solves the problem.

The idea of the San Gabriel Valley as a bounded space is thus simply not true. Many of my interviews involved stories of people driving elsewhere. When young people like the Fung Brothers move to their own place, where do they move? Downtown LA. So the idea of mobility is really something that allows what has been a rapid demographic shift to have settled down into a relatively painless process. Obviously, there’s still a lot of inequality here. But one of the questions I wanted to ask is: what happens when a minority group becomes the majority? And how does that play out economically, socially, and culturally?

One of the other major factors in recent decades has been mainland Chinese money, which has been responsible for much of the built environment of the San Gabriel Valley. But after COVID and certain political changes in China, I think that this investment has become much less prevalent. COVID obviously led to a substantial decline in immigration: it stopped visits back and forth between countries, and it stopped the “yo-yo” residence patterns (where people move regularly between China or Taiwan and California), which many families did consistently. Many people had to decide where to settle long-term. The age of massive Chinese real estate investment is ending; clearly, it’s not a politically expedient thing to do anymore. Ultimately, what the result of this will be, nobody knows. What is clear, though, is that the San Gabriel Valley will stabilize as an Asian American environment.