Mam, a Mayan language spoken both in the highlands of Guatemala as well as in diaspora communities in Mexico and the US, is rapidly becoming one of the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in the San Francisco East Bay region. Mam-speaking migrants are part of a broader trend of Central American migrants in the United States, but they face unique challenges when they move to the US because they often don’t speak Spanish or English. How can linguists support Indigenous language speakers in the United States, and what does starting Indigenous language revitalization programs look like on the ground?

We talked with Tessa Scott, a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Future of Higher Education program at the University of California, Berkeley. She received her PhD in linguistics from UC Berkeley Department of Linguistics in Spring 2023 with a Designated Emphasis in Indigenous Language Revitalization. We spoke with Scott about her work on researching and teaching Mam. Her work spans both formal linguistic theory in syntax and morphology as well as language and cultural learning programs, and she has worked in partnership with native speakers and activists.

Mam has become one of the top ten most commonly spoken languages spoken in U.S. immigration courts. In the East Bay, Oakland Unified School District reports that 1,130 students in their district speak Mam at home. But while their numbers have been increasing, Mam speakers often face challenges receiving services in the U.S. What are some of the challenges that Mam speakers face when they move here?

Many Mam speakers who arrive speak no English, and many times not enough Spanish to communicate clearly or fully understand what they are being told. This is a huge challenge, as without language, they struggle to find transportation to the next city, housing, a job, education, as well as legal help that they have the right to access.

There are three main challenges that Mam speakers face with respect to getting the language services they need. The first is the lack of acknowledgement that a person needs an interpreter to begin with. Indigenous people are often lumped together as a single group with other migrants from Mexico and Central America, and they are often assumed to identify as Latinx and be native Spanish speakers, which are both often not the case. Sometimes Indigenous Guatemalans coming to the US speak very limited Spanish or they are scared and simply say “sí ” (yes) to most questions to avoid potential violence or harm.

The second challenge lies in finding interpreters who speak Mam. A 2019 article in the New Yorker reported that “Mam was the ninth most common language used in immigration courts, more common than French.” There are far more people needing Mam interpreters than there are Mam interpreters, and most interpreting is done over the phone. The last problem with interpreting is that many times the client and the interpreter speak Mam, but they come from different places. While this may not seem like a big issue, significant differences in the language can be present from one town to another, and this can have enormous consequences when interpreting.

Mam is known as a linguistically diverse language, with many dialects, making it difficult to teach in language classes. How did you approach this when you worked with Mam speakers to teach classes at Laney College, and how did you approach these challenges when putting together your teaching guides?

Mam is considered to be the most internally diverse Mayan language, according to Nora England (1990, 2017), and has thus been of interest to linguists studying variation. Two dialect surveys were published around the same time in the 1980s — Godfrey and Collins 1987 and Cojti and England 1986 (an unpublished manuscript) — and together these two works established three major dialect regions of Mam: Northern, Southern, and Western. These are shown in Figure 1, which shows a map of Western Guatemala divided into the three dialect regions.

Most recently, in a 2019 paper, Megan Simon argued for a reclassification of Mam varieties on the basis of phonetic distance research (how similar or distinct words sound). Her re-grouping mostly targets the dialect from the town of Todos Santos, Guatemala as distinct from the rest of the Northern Mam varieties, which she renames the Seleguá group. This is important because Todos Santos is very close in distance to San Juan Atitán, and large numbers of speakers from both towns live in Oakland, as well as countless other cities in the US. Although these Guatemalan towns are close to each other geographically, the varieties of Mam spoken within them are very different.

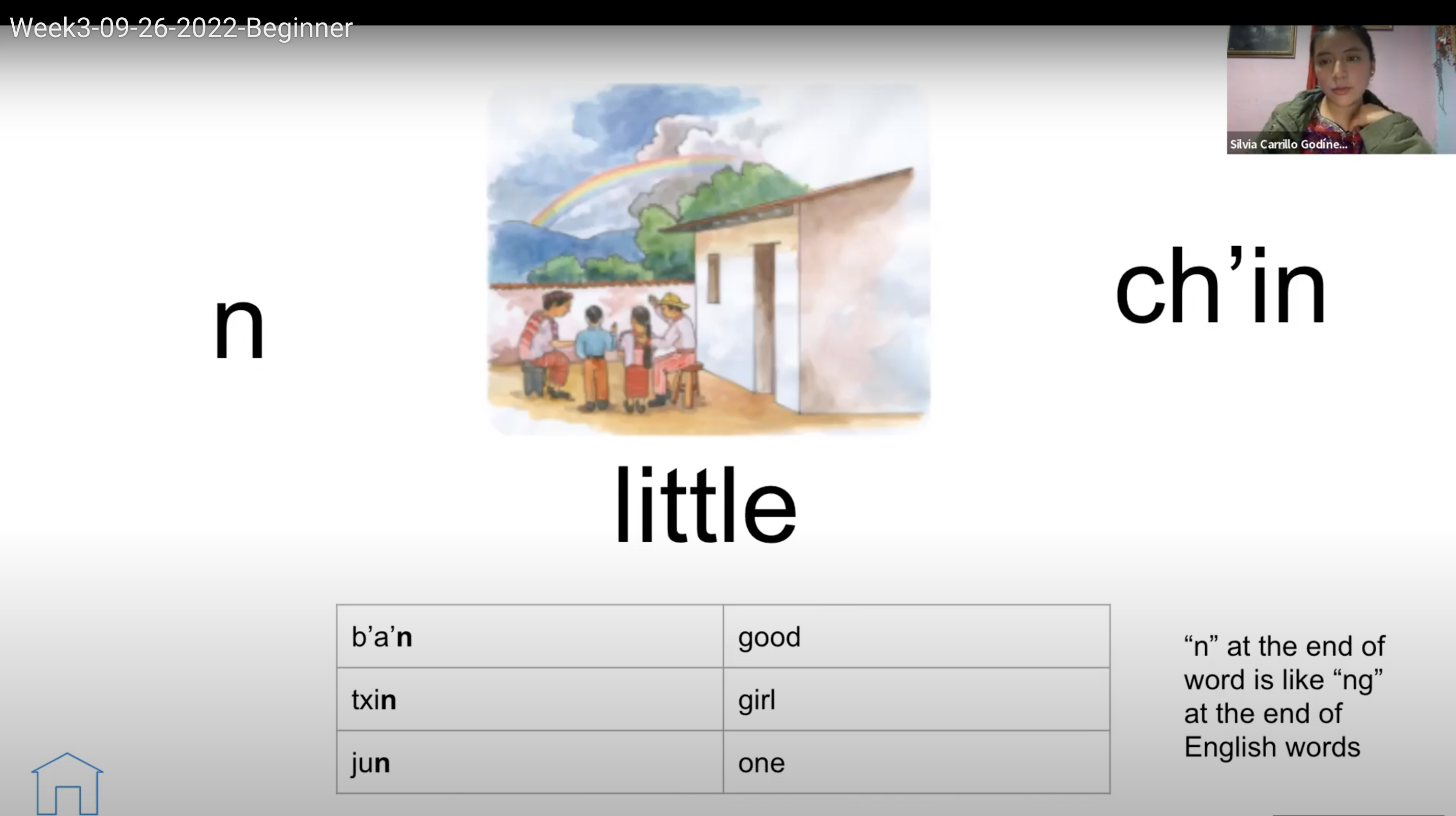

For us, this variation was something important to consider in our teaching. Both of our native Mam speaking teachers, Henry Sales (former teacher) and Silvia Lucrecia Carrillo Godínez, are from San Juan Atitán. This variety of Mam has some unique characteristics but can largely be understood by speakers from the Seleguá region. Our materials are based on this San Juan Atitán variety of Mam. We always make it clear that we are teaching San Juan Atitán (SJA) Mam, and that if someone is also interacting with speakers of Todos Santos Mam, we encourage them to be curious about the differences, and see it as an opportunity to learn more, thinking of their language learning as additive. While this may slow down the learning process slightly, it is worth it on many levels.

The materials used for our Mam language and culture classes are different from the Mam materials published by the Ministry of Education in Guatemala and the Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG), which are based on a “standardized” Mam that was created for purposes of writing and gaining acknowledgment by the government. So if students want to supplement our course with these materials, or even a course in Guatemala, they should be aware that they will find differences.

How is SJA Mam different from “standardized” Mam?

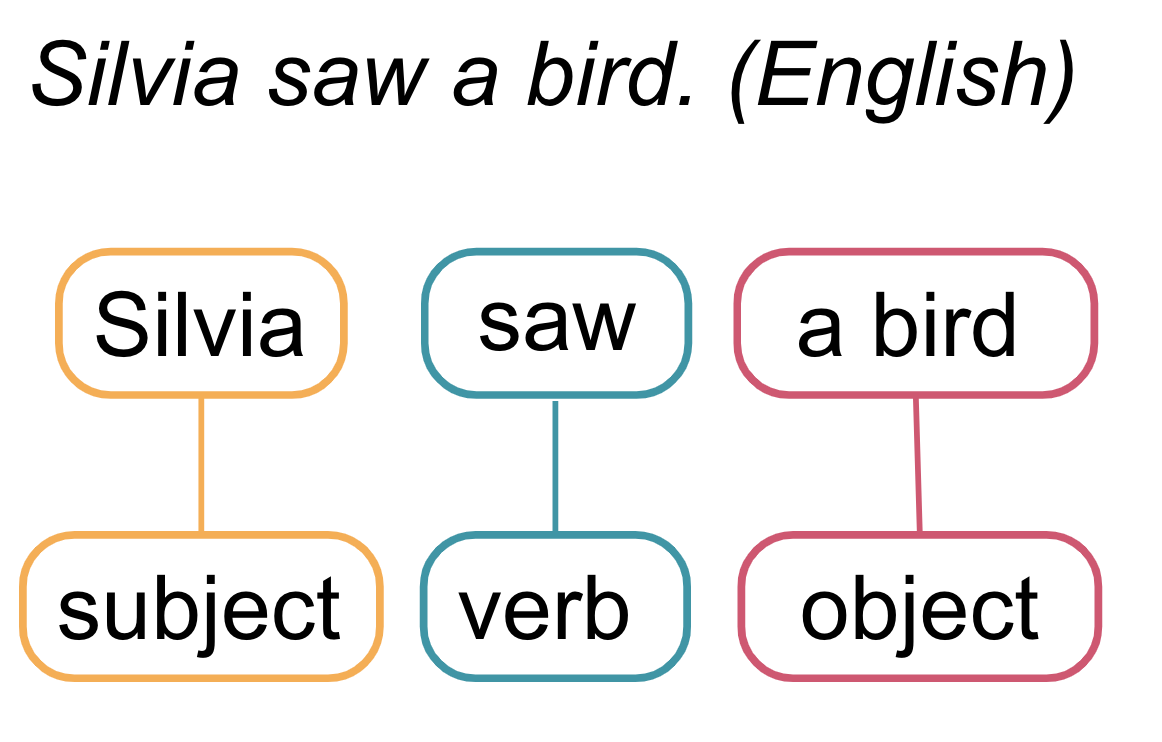

To answer this question, we first need to understand how the grammatical structure of Mam (as a whole) is different from that of English. Let’s start with the order of words. In English, subjects come first in the sentence, followed by verbs, which are followed by nouns. This is illustrated in Figure 2 for the sentence “Silvia saw a bird” in English.

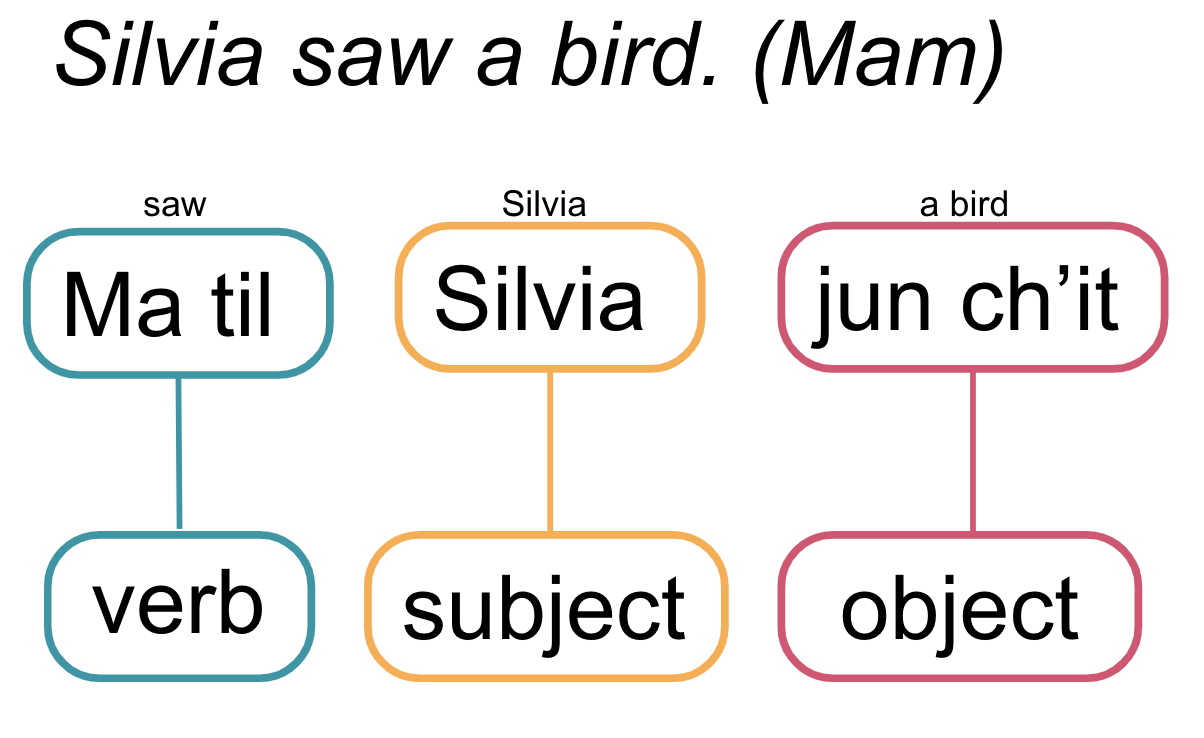

Mam sentences take on a different word order. In Mam, verbs come first, followed by subjects, followed by objects. This is illustrated in Figure 3 for the same sentence, “Silvia saw a bird,” which in Mam is Ma til Silvia jun ch’it.

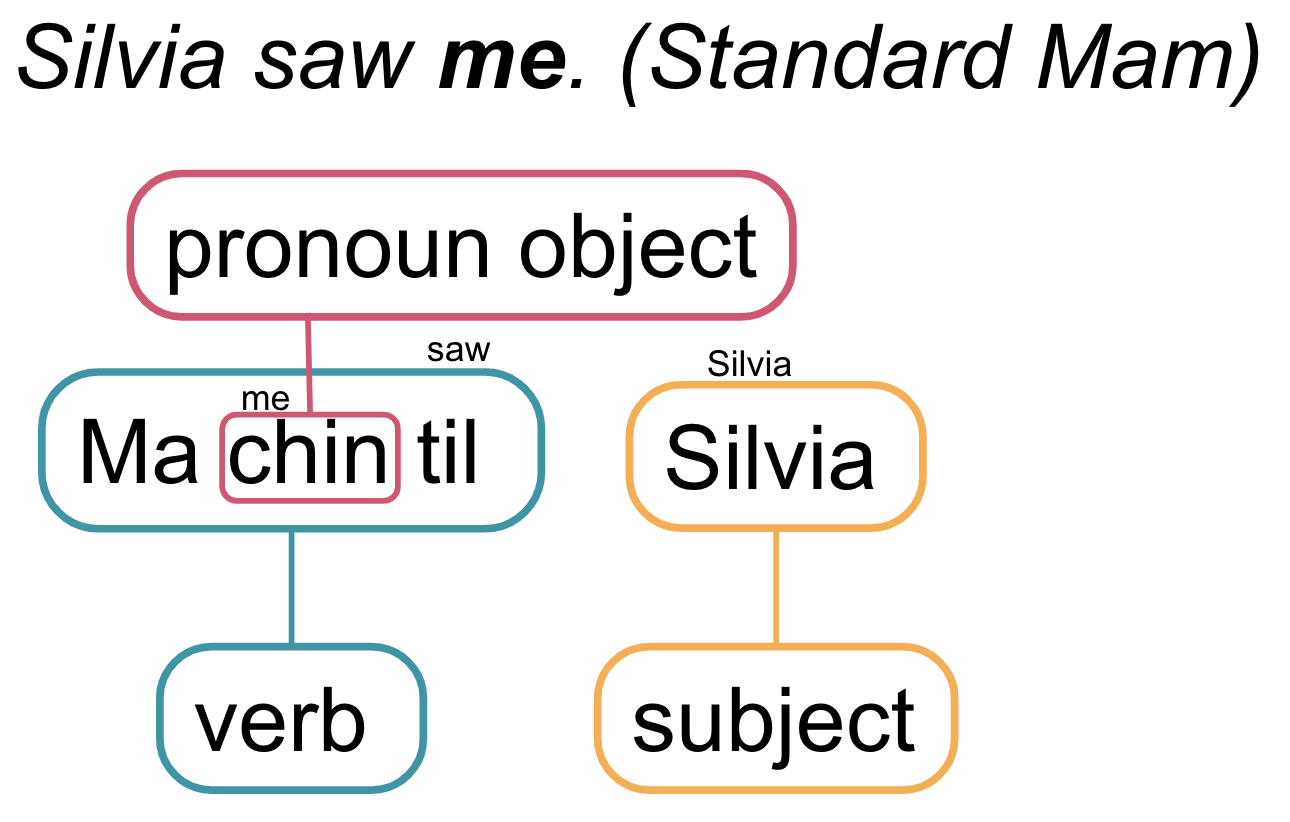

The difference between standard Mam and San Juan Atitán Mam is in the treatment of pronouns. In standard Mam, when the object is a pronoun (like “me,” for example), it sneaks in and appears in between the two words that make up the verb in Mam. This is shown in Figure 4 for the sentence “Silvia saw me.” In Standard Mam, this is written as Ma chin til Silvia. This grammatical phenomenon is similar to pronoun objects in Spanish: Silvia me vió.

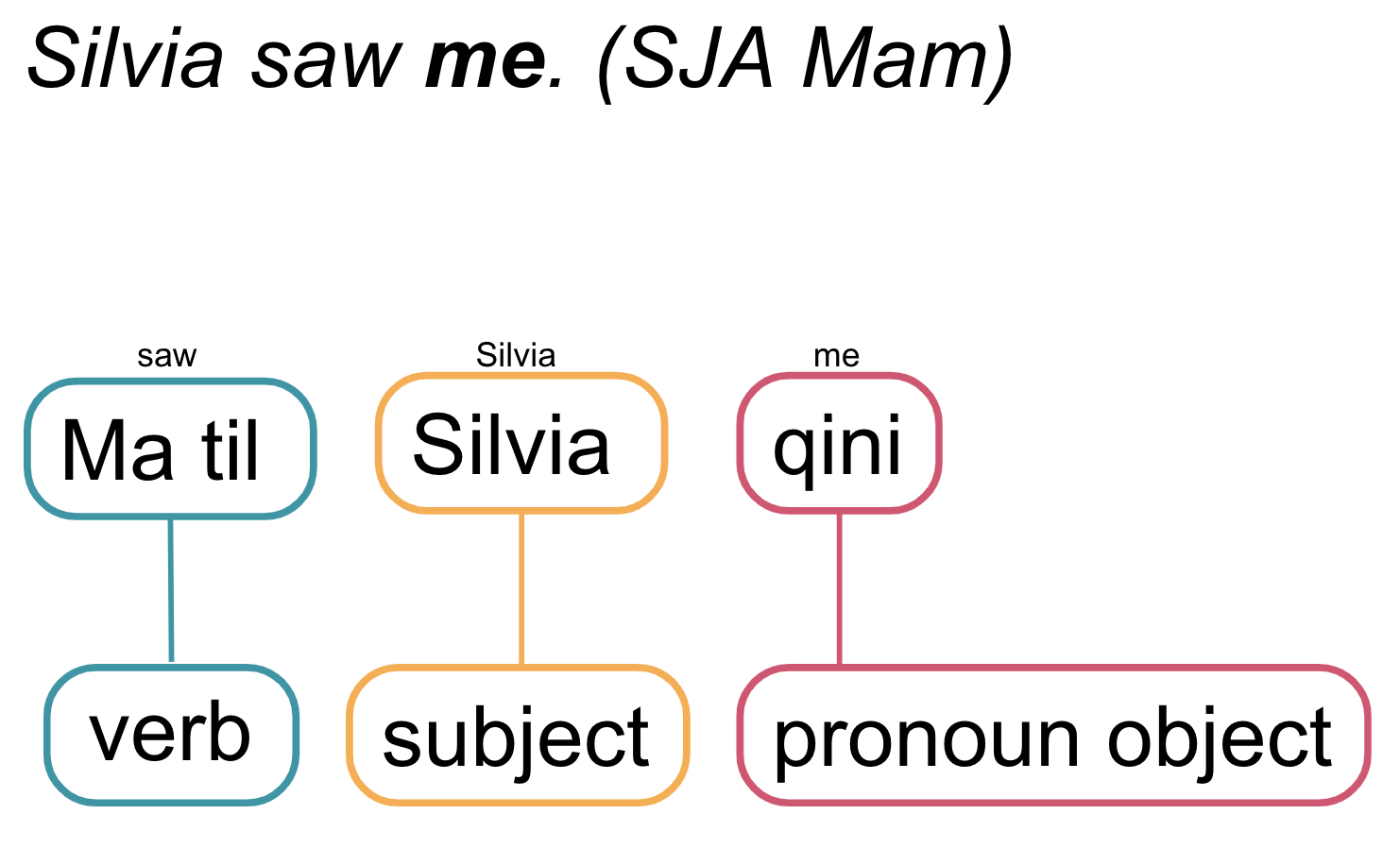

In San Juan Atitán Mam, pronoun objects do not need to sneak into the verb. Instead, pronoun objects often stay at the right edge of the sentence, just like the object ch’it “bird” in Figure 2. The San Juan Atitán version of “Silvia saw me,” which is Ma til Silvia qini, is shown in Figure 5.

This difference between the two varieties of Mam has major consequences for current understandings of the structure of Mam and other Mayan languages. Virtually all Mayan languages employ the grammar in Figure 4, and the deviation from this structure in San Juan Atitán Mam is the basis of the theoretical syntactic and morphological analyses in my dissertation.

While you’re trained as a formal linguist, you also taught Mam classes in the SJA dialect. How did the program to teach Mam classes get started, and what were the goals?

In Fall 2017, I met Henry Sales, who was the Mam language consultant for our graduate-level field methods class in the Department of Linguistics. The goals of this class are to document and analyze the structure of the language through the methodology of conducting structured and focused interviews, called “elicitation” in the field of linguistics, as well as collecting stories and narratives, often called “texts.” (A KQED article about Henry Sales teaching Mam can be found here.)

We students all quickly got to know Sales and realized how enthusiastic and intuitive he was about Mam, his native language. We recorded word lists and started to figure out the phoneme inventory of Mam, as well as a few other grammar topics.

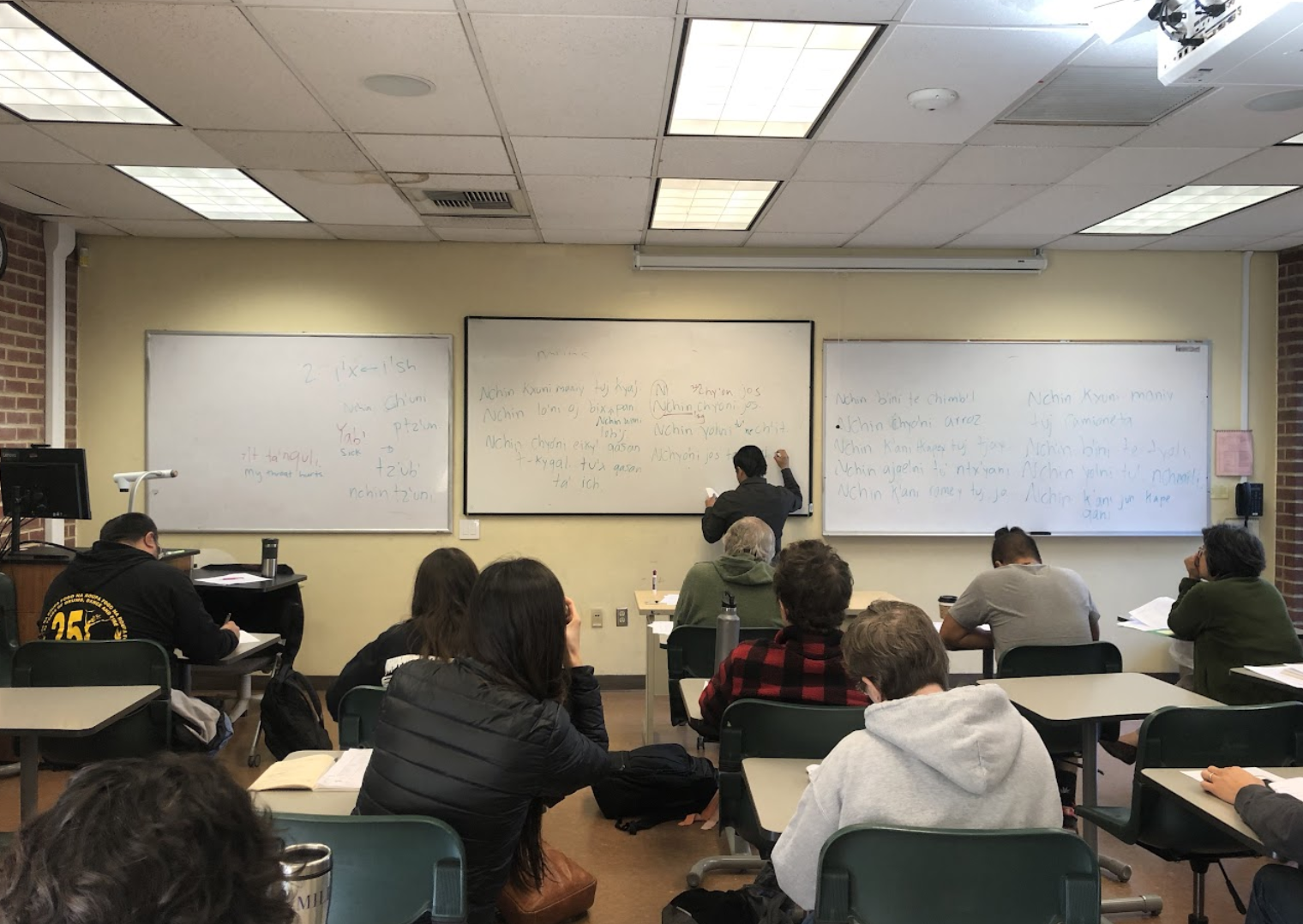

During this time, I developed an excitement about studying Mam, partly due to its rich morphology and syntax and its phonology that was challenging to learn, and partly due to Sales’s energy and passion about Mam. In Fall 2018, Sales was inspired by the Nauatl program at Laney College and began talking with Professor Arturo Dávila Sanchez about the possibility of starting Mam classes at Laney. By Spring 2019, Sales invited me to join his Saturday Mam lessons on Laney’s campus, and I joined enthusiastically.

During this first semester, we met once a week at the Latinx Center on Laney College’s campus, though we eventually upgraded to a medium-sized classroom. The initial audience was small but passionate about learning Mam. Our first students were a few teachers and volunteers in the Oakland community who found themselves in frequent contact with Mam speakers. They wanted to learn Mam as a second (or third) language to connect more deeply with their students and clients and thus were dedicated to learning the language.

Our initial goals were to equip those students with the basics of Mam – for example, how to greet, how to count, and how to talk about food. This would allow them to show the Mam people in their communities that they care and that the Mam speakers not only have the right to be here, but are joyfully welcomed.

As someone primarily trained in formal linguistics, being a part of these language and culture classes was exciting because I was able to bring my different perspectives on the language to our students. The sounds of Mam and the sentence-level grammar of Mam are so different from English that it can be hard to understand even the simplest of phrases. It was very rewarding to be able to use my research on the structure of Mam to help students learn the language.

Your group has been working to provide Mam classes in Oakland and online. Who takes these Mam classes, and what are their goals in learning the language?

Since those first sessions, our class has grown and developed significantly. Many students have returned semester after semester, and this has pushed us to split the class into beginner and intermediate levels, with the latter often splitting into intermediate and advanced learners. Our Mam curriculum has been approved to be used for an official three-level language and culture course at Laney College. Upon completion of the courses, students will receive a certificate of Mam language and culture proficiency. These classes have not yet been offered at Laney, so in the meantime, we have offered the classes online free to anyone who wants to learn Mam. While these online classes are not currently being offered, they may be offered again in the future; updates and all materials can be found at our website: mamclass.com. In the meantime, a new Mam Workshop ran during the summer of 2023 through the UC Berkeley Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (CLACS).

One of the things that makes our class unique is our students and their reasons for taking the class. Most of our students are learning Mam as a second or third language. A large majority of our students are lawyers with Mam clients, teachers with Mam students, and healthcare workers with Mam patients. We also have many students with Mam and Mayan heritage who want to reconnect with the language and their knowledge of their ancestors.

One of our students, an elementary school teacher in Washington, encourages her students to speak Mam in the classroom, whether for counting, prayers, or telling stories. Before she took our class, her students tried to teach her words and phrases, but the teacher found it extremely difficult to identify the sounds she was hearing, let alone recreate them or know how to write them. One of the outcomes of taking our class is that now she can more easily hear differences in sounds that we don’t have in English and have a sense of how to pronounce and write them.

An unexpected positive outcome of moving our classes online is that we were no longer limited to only teaching students who live in the San Francisco Bay Area. Students from all across North America and Mexico have taken our Mam classes. Since 2020, students residing in 20 different U.S. states have registered for our classes. This incredible fact reflects the increasing presence of Mam communities across the U.S., and that these communities are spread out across the country, and not confined to one state or region.

During the pandemic, you’ve had to switch to Zoom teaching in Mam. What have been some of the challenges in switching to the online format from an in-person format?

One of the incredible upsides of the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus moving our classes online, was the ability to reach more students. Additionally, we were able to expand our teaching team to include Silvia Lucrecia Carrillo Godinez, a native Mam speaker living in San Juan Atitan, Guatemala. Having her perspective on the language and culture in San Juan Atitan, her training in Mam literacy, her perspective on cultural topics, and her lived experiences and knowledge about life as an Indigenous Mam woman was extremely influential to our classes. In addition, her energy, patience, and passion became fundamental to our joyful class environment. In 2022, we also officially welcomed Cristina Méndez, UC Berkeley PhD student in Education, to our teaching team. She has taken our classes for many years and has become an invaluable partner in this project.

Teaching online does have some challenges, however. For example, it is harder to have one-on-one time with students, practicing pronouncing hard words, answering their questions about Mam grammar, or simply observing their use of Mam. On Zoom, our options are to go around one-by-one or split into breakout rooms. While this can be seen as a challenge, it has also fostered a sense of community by making sure that everyone has the chance to be heard. As a solution to this, our extensive Quizlet library has many decks with audio so that students can practice on their own with native speaker voices.

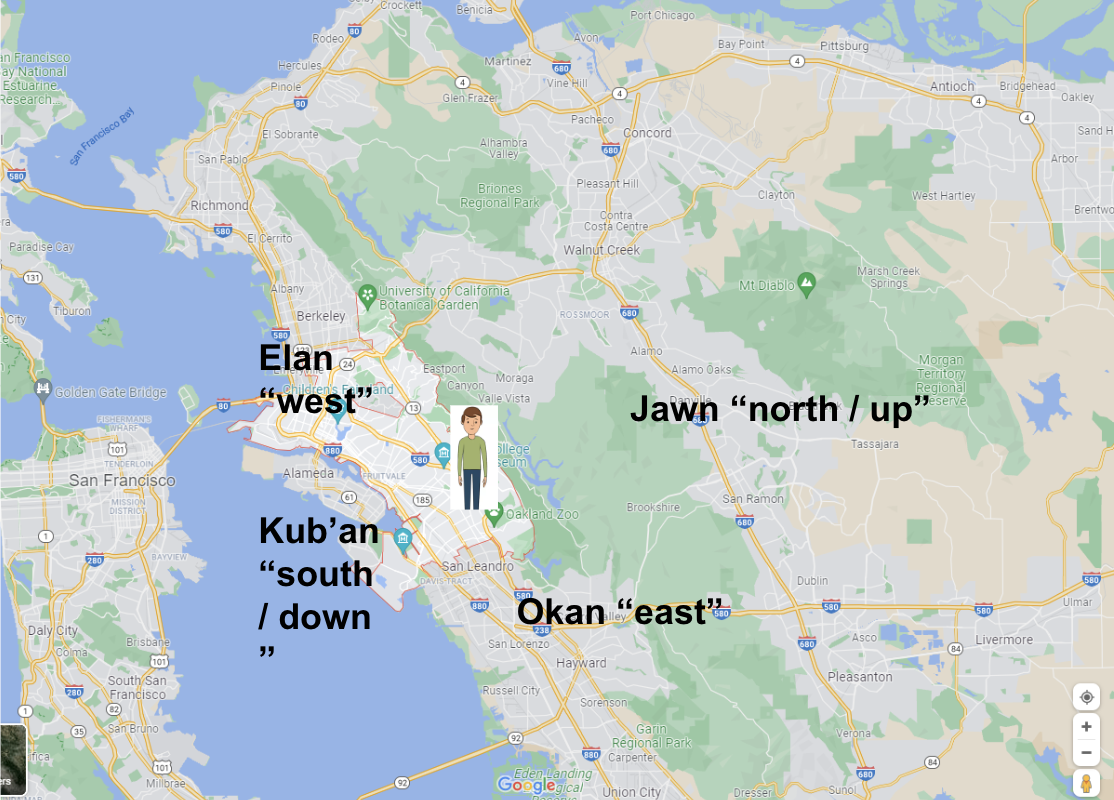

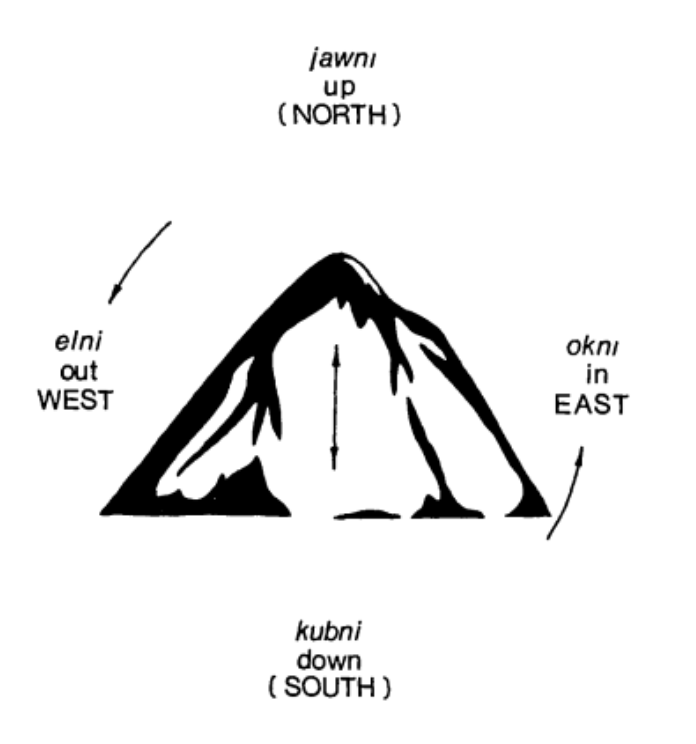

The other challenge lies in teaching land-based language and Indigenous ways of being. For example, the directions that sometimes get translated to “north, south, east, west” exist in a very different way in Mam. Instead of being centered on the poles of the earth (“absolute” directions), the words in Mam are centered around a mountain located nearby the speaker (see Figure 6). Teaching this by standing on a mountain is much easier and better reflects the true nature of these words than simply relying on translations and images.

How has the program worked with Mam speakers in Guatemala, and what has that brought to your work in the United States?

In June 2022, we invited our students to join us in traveling to San Juan Atitán, Guatemala to continue learning not only how to speak Mam, but also about the Mam way of life in the Guatemalan context. During the course of the month of June, around 16 students from seven states in the US, as well as parts of Mexico, traveled to San Juan Atitán.

The main event during our visit was the cultural festival. At this festival, groups were invited from numerous Mam towns to perform traditional songs, dances, and cultural enactments, an act of celebrating diverse traditions and uniting as Indigenous Maya people. The students in our class participated in the festival by giving speeches about the importance of continuing to speak and embody Mam language and culture, as well as highlighting their language abilities by performing short, scripted conversations about why they personally are learning Mam and what they had experienced on their trip so far. (A video of the entire festival can be found here, with our group’s presentation beginning at 3:57:30).

In addition to the festival, while our group was in San Juan Atitán, we held classroom language classes, learned to make Mam food, went on hikes, spent some time learning how to weave, and additionally made connections with other Indigenous peoples from across Guatemala and Mexico, including Nahua, Ñuu Savi, K’iche’, and Kaqchikel.

This trip to Guatemala, and the opportunity for our students to not only learn Mam on its ancestral land, but also connect with individuals and groups, has strengthened many students’ commitment to learning Mam, and strengthened their individual connections to families, teachers, and other networks in Guatemala.

Teaching these classes has also allowed you an opportunity to analyze how linguists conceptualize language acquisition. What have you learned from teaching these courses?

The main thing I have learned is the inseparability of learning language and learning the epistemology, land, cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and history of the people who speak the language. Learning to speak Mam is impossible if it is attempted through translation of non-Indigenous phrases, speaking styles, and ideologies from English or Spanish. It is also impossible to simply study the language alone, removed from culture, traditions, beliefs, and customs.

I also learned that when students have a deep and meaningful reason in their life to learn a language, they can be extremely dedicated and successful in learning that language, even if it is a very difficult language to learn. Our classes have not yet offered course credit, certificate, monetary benefits, or even grades. Some of our students decided to take our class to reconnect with their heritage and to speak the language of their ancestors, who were robbed of the opportunity to freely pass on their language.

I learned from watching these incredible students that, when the reason for learning is so meaningful, students can overcome any challenge they face in learning, whether staying up for classes between 9-10:30pm for students on the East Coast, or trying to produce voiceless bilabial implosives, a type of whispered sound with no vocal vibration that is made with two lips and requires sucking air in, and not pushing air out.

I learned that these meaningful reasons were diverse and did not follow a formula. Some students work in the legal field, and they deal every day with the language challenges that Mam immigrants in the US face. By taking our Mam classes, they make the statement that overcoming such a language challenge includes them taking a step toward their clients, and that it is not the sole responsibility of Mam immigrants to learn the widely used Spanish and English. We have a duty to learn Mam, too.

Some students are teachers themselves, working with youth who question daily whether to wear their traditional traje to school, whether to speak Mam, whether to learn traditional dances and music, or whether to learn traditional prayers in Mam. Some students are healthcare professionals, working with patients who have the right to receive healthcare that they understand in their native language. Some students work for non-profit organizations providing various types of aid to immigrants. Some students are researchers in linguistics, education, anthropology, environmental studies, and psychology. Some students simply want to better communicate with their Mam-speaking friends and neighbors.

Each semester, our students do a final project. Each semester, I am blown away by what they create. In the past, students have developed presentations about their families, translated children’s books and poetry, written original stories and poetry, and created videos about a day in their life or a trip to the zoo with Mam-speaking middle school students narrating their experience and observations, and created presentations about Mam-speaking individuals whom they interviewed. (Examples of final projects can be found on the class website.)

The creativity and heart revealed in these projects were undoubtedly impressive and inspiring, and also illustrative of the use of technology to not only learn and study Mam, but to create art and use Mam as a medium of self-expression. These projects embody the students’ commitment to learning not only the Mam language, but Mam ways of being.