How has climate change become a security issue? Geographer Brittany Meché argues that contemporary anxieties about climate change refugees rearticulate colonial power through international security. Through interviews with security and development experts, her research reveals how the so-called “pragmatic solutions” to climate change migration exacerbate climate change injustice.

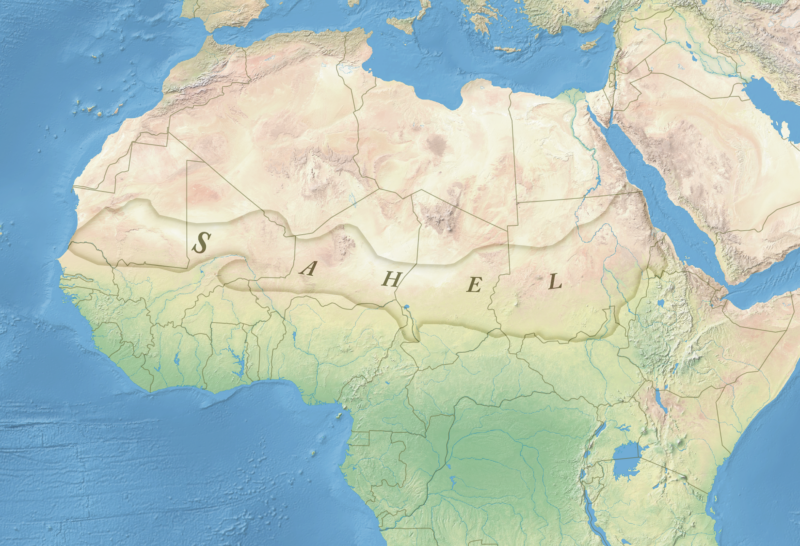

For this interview, Julia Sizek, Matrix’s Content Curator, asked Meché about her forthcoming article in New Geographies from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, which considers how expert explanations of climate migration rework the afterlives of empire in the West African Sahel, an area bordering the southern edge of the Sahara, stretching from Senegal and Mauritania in the West to Chad in the East.

Meché is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Affiliated Faculty in Science and Technology Studies at Williams College. She earned her PhD in Geography from UC Berkeley. Her work has appeared in Antipode, Acme, Society and Space, and in the edited volume A Research Agenda for Military Geographies. Meché is currently completing a book manuscript, Sustainable Empire, about transnational security regimes, environmental knowledge, and the afterlives of empire in the West African Sahel.

Q: Climate change is happening everywhere, but the effects of climate change are highly variable. Your research examines how climate change has come to be seen as a security issue for organizations like the UN and governments like the EU and US. How do they understand the problem of climate change in the West African Sahel?

One of the things that I examine in my research are the interrelations between environmental knowledge and security regimes more broadly. In so many ways, environmental knowledge can’t be divorced from militarism, empire, and other forms of institutionalized power. One of the things that often surprises my students is when they learn that one of the reasons we even know climate change is happening is because the US military poured billions of dollars into environmental science after World War II. That historical context is important, but in the contemporary moment, the consequences of what some scholars have described as “everywhere war” mean that so many aspects of social, political, and economic life become infused with and tied to the logics and infrastructures of security.

The West African Sahel, where I conduct my research, is a region that is already experiencing the impacts of climate change, from rising temperatures to erratic rainfall patterns. At the same time there have been increasing rates of different forms of armed revolt, which get lumped together as Islamic terrorism. It becomes easy for foreign militaries to say that worsening environmental strain is linked to social and political collapse. In response, foreign militaries propose fortifying the local security sector through security cooperation agreements, military training, and investments in border security. In that way, security solutions replace any careful consideration of the structural inequities of climate change. My research seeks to challenge these approaches through a detailed accounting of how these kinds of security imperatives further imperil already vulnerable communities.

Q: In your forthcoming article on border security and climate change in the West African Sahel, you address how security actors like the UN respond to what they see as the threat of climate refugees. How are climate refugees understood as a security problem?

The issue of climate refugees was one of the most vexing issues I encountered during my research. There are no formalized legal conventions about what constitutes a climate refugee or climate migrant, so the terms themselves are capacious and vague in ways that make it difficult to know what they actually describe. Is a climate migrant someone who is displaced during an acute event like a hurricane or earthquake? Someone who is no longer able to grow crops and chooses to relocate elsewhere? Someone who lives in a coastal area or on an island where sea level rise makes reliable habitation less feasible? Or all of the above? And, if so, how can we alter a global refugee system that many scholars — like Harsha Walia, Leslie Gross-Wyrtzen, and Gregory White — have noted is already at times violent, strained, and ineffectual, to accommodate these different categories?

But more vexing than these conceptual and legal indeterminacies are the ways that present investments in border security and fortification make use of the figure of the climate refugee to whip up xenophobic fears. In my article, I note the ways that climate refugees, almost always depicted as people of color, become ways of making climate change knowable and actionable. Climate change becomes located on the body of migrants of color amid claims that “hordes” of climate migrants from the Global South will inundate the Global North. The embodiment aspect is key, as the literal bodies of these migrants come to signal and stand in for climate change as a security problem. This often leads to calls for “pragmatic solutions” like more border security and more heavily regulated immigration systems.

Q: How do ideas about migration align (or not) with the realities of how migration works in reality?

I think popular framings of migration in and from the Sahel miss the ways that circular migratory patterns have been a staple of life for centuries. The Sahel has a number of pastoral communities that migrate with their herds. There are also cycles of migration between rural and urban areas, and education and religious pilgrimages that take place. This is not to say there have not been people forced to move because of violence, or because of economic or environmental stress. But many aspects of how and why migration happens get lost when migration is simply offered up as a problem to be solved.

One central aspect of this issue is how my informants framed climate change migration as a South-North issue: that is, people from the Global South going to the Global North. In reality, most migration is South-South. Most of the migration happening in the West African Sahel and across the African continent more broadly is intra-regional migration. But this fact does not receive the same level of attention. I had informants at the International Organization of Migration admit that, while their figures show the predominance of intra-regional migration, for funding purposes, they had to frame their work as speaking to the “migration crisis” in Europe. The fear of Africans inundating Europe obscures the realities of this South-South migration.

Q: Your research also considers the longer history of anxieties about migrants by showing how contemporary takes on climate change migration have supplanted and reinforced colonial anxieties about overpopulation that bring back Malthusian ideas about scarcity and overpopulation. How do these anxieties appear in security policy, and how do security experts think about these colonial legacies in their work?

In many aspects of my research, it seems that Malthus never really left. The West African Sahel has some of the highest birth rates in the world, and that fact lends itself to easy, though ultimately false, claims that overpopulation is at the root of the region’s problems. Still, for me, it was important to trace the ways that the different institutions I study absorb criticisms and attempt to re-orient their work. For instance, when informants at different UN agencies, such as the UN Development Program (UNDP), UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and International Organization of Migration (IOM), would mention population in the Sahel, they would do so with the acknowledgment that it was a “third rail” issue. So even as the ghost of Malthus lives on, I think it’s important to account for different mutations.

Similarly, when interviewing US military officials working for US Africa Command (the Department of Defense’s command dedicated to African affairs), they were very mindful of accusations of colonialism and empire, and attempted to cultivate what I call in my work a “non-imperial” vision of US empire. That is to say, their disavowals, far from being just a PR move, were being used to strategize new kinds of circumscribed actions that would allow for a US presence in the region without inviting anti-imperial protest.

Q: You’ve mentioned that many of your interlocutors are experts in the international development and security fields. How did you conduct your research on such a transnational project, and how did you get access to the experts you interviewed?

I knew at the outset that this project had a number of different threads, including multiple actors, and therefore demanded a multi-sited approach. I started in Washington, DC, where I interviewed US government officials who put me in touch with informants in Stuttgart, Germany, the headquarters of US Africa Command. In turn, these informants put me in touch with other military, diplomatic, development, and humanitarian workers in Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Niger. I also previously worked at the US State Department and have family ties to the US military, which facilitated access.

But still, you can never underestimate the usefulness of showing up. Many of my most memorable interviews and points of contact were serendipitous. Similar to most fieldwork, it’s all about cultivating relationships. I primarily used snowball interviewing, which involved seeking additional recommendations from existing contacts and using those suggestions to map out a network of informants. Given their positions in “elite” institutions, many of my informants were very much interested in preserving their anonymity, especially when they offered criticism of work they were doing within those institutions.

Q: While this new article focuses on migration, your broader book project focuses more on the role that a network of experts plays in constructing a past and predicting a specter of future catastrophe in Sahel. In addition to climate migrants, what other climate issues appear in your book?

The broader book project, currently titled Sustainable Empire: Nature, Knowledge, and Insecurity in the Sahel, makes the central claim that attending to what has happened historically — and what continues to happen in the West African Sahel — is crucial for understanding the possibilities of just global environmental futures. It supports this claim in a number of ways. First, it explores how environmental knowledge in and from the Sahel helped assemble a conceptual and institutional bedrock for global climate change knowledge. I do this through a critical genealogy of desertification, considered the first global climate change issue in the mid-20th century. I then trace the place of West Africa in predictions about the “coming climate change wars,” reflecting on how racial and gendered fears helped set the stage for what became the global war on terror. The book then concludes with a consideration of the kinds of climate solutions being workshopped in the region, ranging from ongoing security projects to large-scale green-tech projects.