In 1997, the United States shifted its immigration policies, leading to the intensified deportation of individuals with criminal backgrounds back to their country of origin. As a consequence, members of gangs that originated in Los Angeles — including many Salvadorans who were brought to the U.S. in their youth — were deported back to El Salvador as their country was recovering from civil war. Prior to 1997, El Salvador did not previously have any powerful gangs; however, the rise in deportations contributed to the rise of MS-13 and Barrio 18, which quickly gained territorial control in parts of the country.

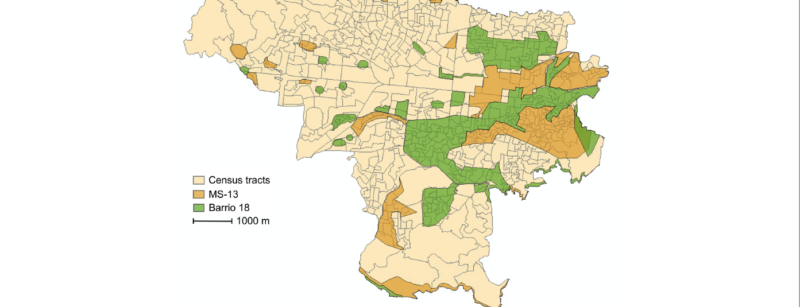

In a October 2019 paper, “Gangs, Labor Mobility, and Development,” Carlos Schmidt-Padilla PhD Candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Political Science, together with Princeton’s Nikita Melnikov and María Micaela Sviatschi, examined what happens to the populations that live within territories controlled by gangs, who limit the mobility of individuals. They found that individuals within gang-ruled areas have significantly less income and lower-quality education — and experience greater inequality — compared to individuals living just 50 meters outside of gang-controlled territories.

In a October 2019 paper, “Gangs, Labor Mobility, and Development,” Carlos Schmidt-Padilla PhD Candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Political Science, together with Princeton’s Nikita Melnikov and María Micaela Sviatschi, examined what happens to the populations that live within territories controlled by gangs, who limit the mobility of individuals. They found that individuals within gang-ruled areas have significantly less income and lower-quality education — and experience greater inequality — compared to individuals living just 50 meters outside of gang-controlled territories.

Cited by The Economist in early January, the research has brought new attention to some of the broader effects transnational gangs have on communities. We interviewed Carlos Schmidt-Padilla to learn more about the researchers’ key methodologies and findings. (Note that responses have been edited for length and clarity).

What inspired your research on labor and social mobility and development in El Salvador with respect to MS-13 and Barrio 18?

Gangs have been a big issue in Central America since the 1990s, when individuals who had criminal backgrounds in the United States, including many of those involved in the notorious 18th Street and MS-13 gangs, were repatriated to their countries. 18th Street is a Mexican gang that a lot of Salvedorans joined, while MS-13 evolved from numerous neighborhood “cliques” across California. In 1996, the United States passed the Immigation Enforcement Act, and in 1997, they started mass deportations of Salvadorans, mostly undocumented with criminal backgrounds, back to El Salvador. They were deported at a time when the country was recovering from a civil war, and they found a location from which to expand.

I’m from El Salvador, and all my life I’ve grown up hearing that gangs have control over the country and inflict both physical, economic, and emotional damage to families. What inspired this piece was an effort to understand the mechanisms through which gangs affect social and economic development. In particular, we found that one of the main reasons you see such a detrimental economic impact for individuals in gang-controlled areas is because of the mobility restrictions they place on individuals. This is not to say that entrance into and exit from these specific territories is completely restricted, but there are limitations. These restrictions range from limits on mobility, where it becomes difficult to enter and exit gang-controlled neighborhoods, to the stigmatization of individuals who live in such neighborhoods. The restrictions and stigmatization then affects your labour outcomes and opportunities.

In El Salvador, for example, an individual with tattoos is more likely to be suspected as a gang member. The police tend to stop and scan individuals for tattoos that are exclusive to gangs and they will stigmatize you for it. Following a Supreme Court decision in 2015, gangs have been considered terrorist organizations in the country. If the police think an individual is a gang member, they will arrest that person for illicit associations.

Your research focuses on gang activity and control in urban settings, where state and non-state actors coexist. What does that dynamic look like?

Our paper focuses on a hybrid setting, where there is a strong presence of both state and non-state armed organizations. There is anecdotal evidence that the state needs the gangs’ approval to enter into these territories. Likewise, when politicians run for office, they need the permission to enter gangs’ territories for campaigning purposes. In the 2014 presidential elections, for example, all the major political parties negotiated with gangs for permission to campaign in their territories. There is now an ongoing court case over these illicit negotiations. It’s very difficult for political figures to operate in all the Salvadoran territory without gangs. A significant portion of the political class has been co-opted and has to participate in these negotiation dynamics.

With respect to the police and security forces, there have been cases where gang members have entered into the police or military academy. Within the Ministry of Defense, for example, there were 300 applicants who were suspected of having connections to gangs in the last recruiting call. Given their nature, these institutions have been able to resist infiltration by such groups, and there have been discussions on better screening mechanisms for applications, such as a polygraph exam.

Your paper made use of diverse methodologies — including spatial regression discontinuity design and difference in differences analysis — to estimate the causal effect of living under the rule of gangs. What particular advantage did these two methods provide for your research?

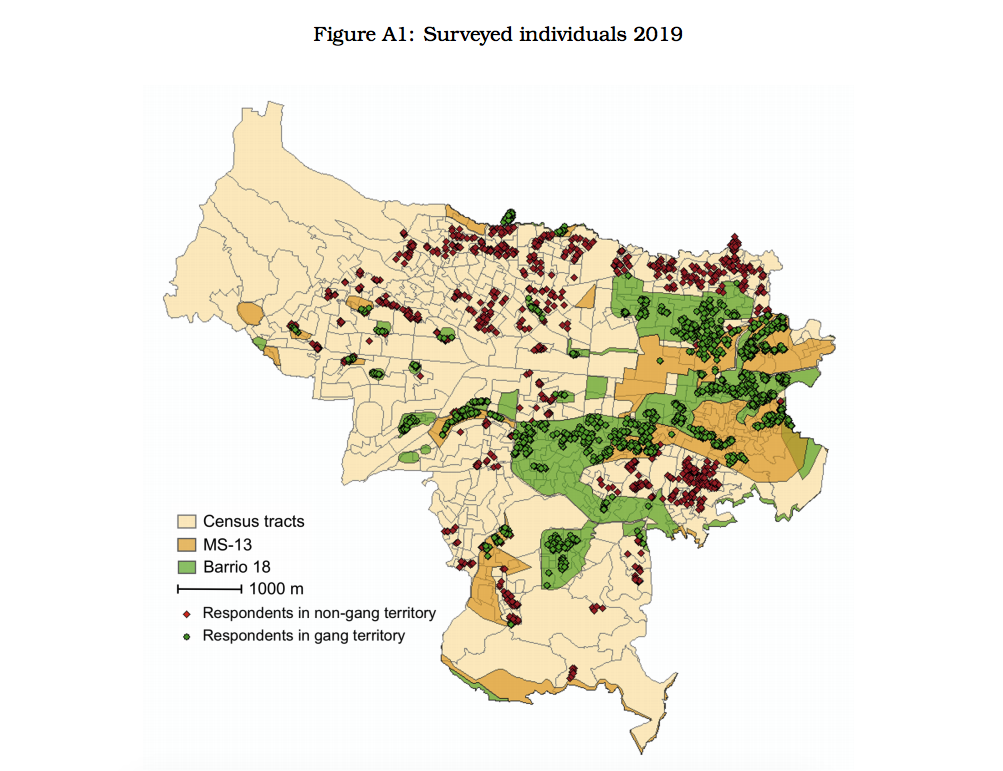

The regression discontinuity design allowed us to compare individuals living immediately 400 meters within and outside of gang territory. This ensured that the populations we were comparing are relatively the same, with the gang presence as the only difference. We go through a painstaking process in the paper to show that there were no other differences between the two populations we were looking at prior to the arrival of gangs in San Salvador. This took into account information from prior to the arrival of gangs and after; demographics, such as the number of households present; and the presence of state infrastructure. So we were then able to compare prior and post economic growth in areas that had gang homicides in the early days of gang presence in the country.

You describe how some gangs set up checkpoints against rival gangs and the state. Can you explain this set up?

There are gang collaborators, for example, between streets, and they’re tasked with overseeing whether people coming into the neighborhood are familiar or strangers. If the individual is a stranger, then that person is intercepted and questioned. If distribution firms want to do business in a gang territory, they pay a toll extortion, while businesses within gang territory are charged a weekly or monthly extortion fee.

Individuals living in gang territories earn half the amount of income compared to those living 50 meters outside of gang territory. Additionally, they are subject to extortion, or renta, which roughly translates to rent, which applies to families and businesses.

I’ve done research on the Northern Triangle of Central America (Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador), and we find that in Honduras, there is a similar tax called impuesto de guerra, or war tax, because of the competition between MS-13 and Barrio-18 and the state.

The gangs want to limit conflict, maintain control over the territories they function within (to extract resources via extortion), and avoid bloodshed, which might attract police attention. In doing this research, it was interesting to learn that, during Christmas and Easter, gang members ask for a bonus extortion payment. Likewise, when one of their members passes away they ask the community to help cover the cost of the funeral.

It is important to note that a lot of these gang members come from highly marginalized communities, and sometimes individuals are not given the option of joining, but rather face life-threatening consequences if they do not join. There are high degrees of school desertion because of the recruitment of 10- to 12-year-old students, particularly among males.

Individuals living in gang territories earn half the amount of income compared to those living 50 meters outside of gang territory. Additionally, they are subject to extortion….

Aside from checkpoints, what other mechanisms are in place to ensure that the gangs’ territorial control is sustained?

People become in part dependent on the gangs present in the territory, and some within the territories are able to benefit from the informal economies that gangs create. If you earn a certain ranking within the organization, then your family is able to earn a “pension” from the gang. This is similar to mafias, for example, in Italy and Japan. On the other hand, you have families who have to close their businesses earlier within the gang territories. You have to be careful entering or exiting gang territory, as sometimes gangs check your ID to ensure you are from the neighborhood and not from a rival one. Stigmatization of living in gang territories also influences someone’s likelihood of being hired, or even in working in rival gang territories, as your address is used as a cue for whether you might have ties to gangs.

Did you encounter any ethical dilemmas in the course of conducting this research?

One of the ethical dilemmas we faced came up when doing the survey, as we asked the participants more detailed questions than what was available to us in the census. These questions ranged from their perceptions of freedom of mobility to cultural attitudes. However, we knew we had to prioritize the security of the participants. We worked with a firm experienced in conducting in-person surveys in these communities and set up a time frame for all the surveys to be conducted from 6AM to 11AM, when gangs are less active.

Were there any surprises while conducting the research, and what do you hope to see emerge from your research?

Were there any surprises while conducting the research, and what do you hope to see emerge from your research?

We never thought there would be such strong impacts of mobility mechanisms. If you ask anyone the question of whether gangs are beneficial to development, they will mostly likely answer no. We think this paper’s main contribution is helping us understand exactly how gangs hurt development for communities within gang territories. This is the first step in then understanding how we can overcome these imposed challenges.

It is difficult in El Salvador because voters want quick solutions, and they then support tough-on-crime policies. For example, in the early 2000s, the government passed iron-fist policies that facilitated arrests of people based on their tattoos. With the increase in incarceration rates, you have gang members in prison who become more organized and coordinated. Short-sighted policies are what got the country into this situation, and they might have long-term consequences aside from the ones we study in the paper. El Salvador is close to surpassing the U.S. in terms of incarceration per capita, which is alre the highest in the world.

Right now, the new government that came into power in June 2019 is launching a territorial control plan, which seeks to regain the territory controlled by gangs. This is in part an acknowledgement, particularly from the Ministry for Security, that territories have in fact been lost to gangs and that there is an urgency to regain them. This is a step in the right direction in trying to regain the territories and build trust in order to provide better services for the communities. There seems to be much more coherence in this plan compared to previous tough-on-crime approaches. Both the U.S. Embassy and international organizations have expressed their hopes in this plan.

Is there anything else you think people should understand about these gangs?

When people think of gangs in the U.S. they tend to think of them as purely terrible organizations. This is in part accurate, but there needs to be more understanding of the positions of individuals who are forced to join. There are kids who grow up living their entire lives in gang-controlled territories, for example, who are forced to join and then cannot leave the organization.