China’s Cultural Revolution aimed to reshape the social and political order of China by purging elements of feudalist and bourgeois society, including through confiscating property. In 1966, millions of objects were taken from homes by independently organized and unofficial groups associated with Red Guards, a student-led paramilitary movement that supported the revolution. But what happened to the objects after they were seized?

Puck Engman, Assistant Professor in History at UC Berkeley and a historian of China in the postwar era, talked with Julia Sizek about the lives of these objects. More broadly, his research concerns the reorganization of state and society in the first 30 years of the People’s Republic of China, and the transition from command economy to market economy at the end of the 20th century.

This interview is based on Engman’s publication, “What Right to Property When Rebellion is Justified?: Revolution and Restitution in Shanghai,” which is published in Justice After Mao: The Politics of Historical Truth in the People’s Republic of China.

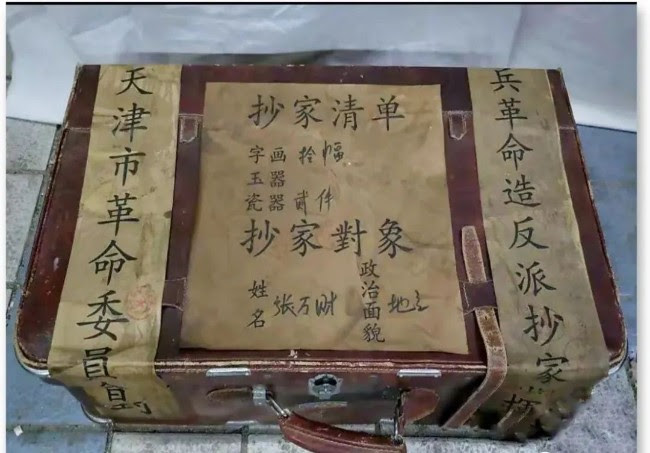

During the Cultural Revolution, China’s Red Guards confiscated so-called “feudal” and “bourgeois” property from private citizens. Your research shows how this confiscation happened in practice. What did this seizure look like on the ground?

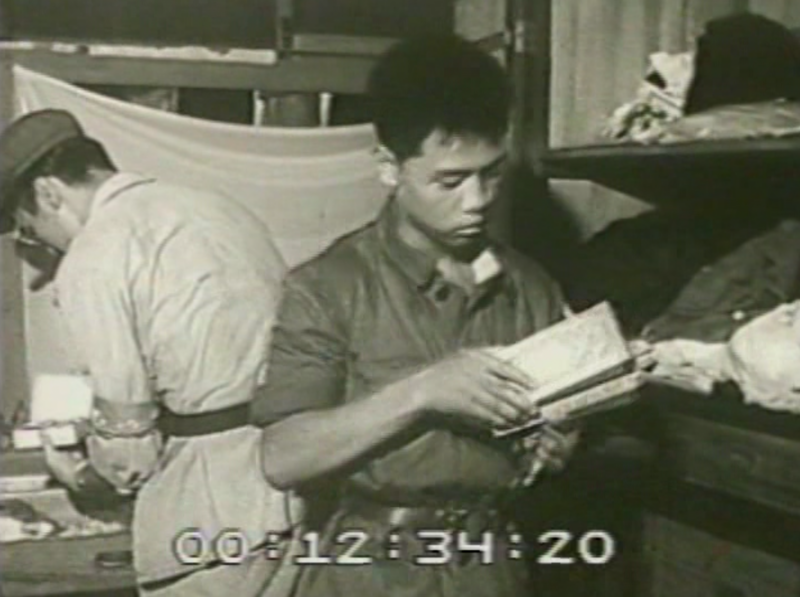

The late summer of 1966 is known among historians of China as “Red August” due to widespread violence and vandalism. This involved Red Guards raiding and ransacking hundreds of thousands of homes across China. “Red Guards” was the name used by the youth organizations that had formed at universities and schools around the country to join a new political movement: the Cultural Revolution. In August, they began entering private homes, often humiliating, threatening, and even beating up residents in the process. While their primary aim was to uncover evidence of counterrevolutionary plots, they more often came across items such as bronzes, books, watches, pianos, and rugs. They seized such items all the same on the grounds that they were vestiges of feudal tradition or bourgeois lifestyle.

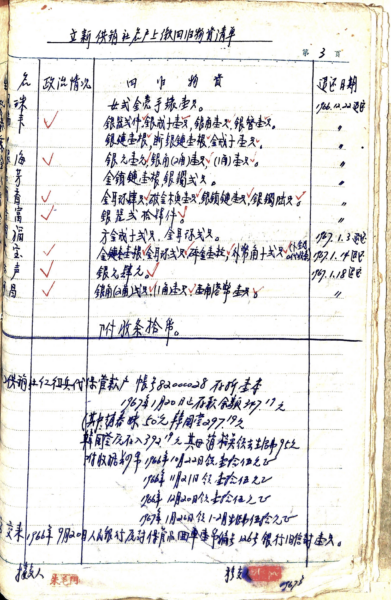

I became curious about what happened to all these confiscated belongings. We are talking about literally tons of gold and silver, and millions of books and antiques. Where did it all end up? This question had me follow a paper trail that led away from the street-level politics that we picture when we think of the Cultural Revolution, into storage rooms and warehouses where the objects were stored. Here, I discovered the other side of looting, the bureaucratic side, where the concerns were with logistics, storage space, and ultimately restitution.

The shift of perspective to the bureaucratic side made it clear to me that party and state played an active role in the looting. In fact, when the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee set up a new government in the city, in the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, one of its first priorities was to set up a group dedicated to the handling of confiscated belongings.

What were some of the practical challenges that came with seizing private property?

I should start by pointing out that the confiscation of personal belongings during the Cultural Revolution was a major departure from the established script for mass movements. If there was such a thing as a normal operating procedure in Maoist politics, this was not it. This made it easy, in the years after Mao’s death in 1976, for the new political leadership to declare the house raids illegitimate, one of many excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

This would not have been possible before Mao’s death. Mao was the main author of the Cultural Revolution and an enthusiastic and public supporter of the Red Guards.

From day one, however, the sheer amount of confiscated items presented a logistical problem that local governments could not ignore.

In the city of Tianjin, the loot was enough to fill 52 warehouses, or the equivalent of about 60,000 square meters of storage space. The situation was even worse in Shanghai, where there had been over 10 times the number of house raids that had been reported in Tianjin.

Officials in Shanghai had to get creative to solve the storage crisis. They were able to take advantage of the shutdown of places of worship in the Cultural Revolution: churches and temples became makeshift warehouses, as did a colonial-era entertainment complex in downtown Shanghai. The entire east wing of the Jade Buddha Temple, measuring over a thousand square meters, became a storage space for seized antiquities.

Many seized items remained in such impromptu storage sites for years. When owners were finally able to retrieve their belongings, they would sometimes find that an elegant dress had been ruined by rainwater leaking in from the ceiling or that a scroll painting had been ruined by mildew. The political leadership was aware of this problem. In fact, only months after the raids, concerns about the upcoming rainy season prompted the very first Communist Party directive on the handling of confiscated goods, “which was primarily an order to hand over the loot to the proper authorities, but also opened for limited restitution for working-class household. This was, however, a problem without a quick fix.

What were some of the common paths for these objects to take after they were confiscated, and what are the traces of objects that you have found in the archives?

In Shanghai and other major cities, the Red Guards delivered their loot to local factories, schools, and government offices by truckloads. Responsibility for processing all these objects was shared across several arms of the local administration.

All contraband had to be handed over to the police. This included the firearms that Red Guards would display, proudly, as evidence of the counterrevolutionary plots they had thwarted. Much more common, judging from the documentation I have seen, were mahjong sets. Gambling was illegal in China at the time, but remained widespread and a low priority for the police. But for the Red Guards, gambling symbolized that reactionary attitudes were still prevalent in Chinese society. The movement was possibly the most extensive clampdown on gambling in Chinese history.

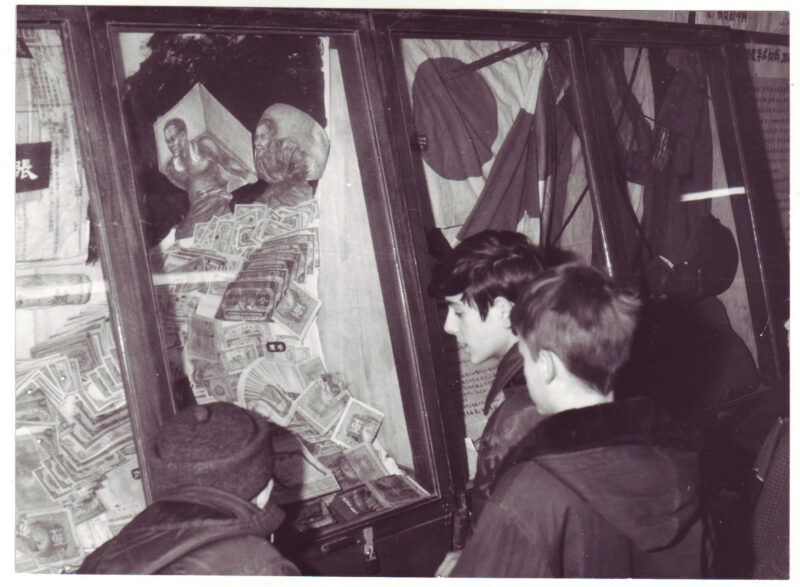

A unique challenge was presented by the confiscation of rare books and antiques. Historian Denise Ho has studied how cultural workers committed themselves to cultural preservation in the midst of the movement’s iconoclasm. Building on her work, I have looked at the decisions that went into separating common trinkets from cultural heritage. Lesser antiquities, mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, were approved for export. In addition to lessening the burden for museums and libraries in China, such exports promised to generate foreign exchange, a rare and highly coveted resource for a country that had been cut off from much international trade. A great deal remained in the warehouses, but the artwork that made its way to Hong Kong was enough to shake up the local art market in Hong Kong, which was suddenly flooded with new items.

Chinese documents show that rare antiques were sometimes recovered by the Shanghai Museum from Hong Kong. Other objects likely remain in poorly documented private collections in Hong Kong or have become part of collections around the world. It is hard to say. Today, art museums are expected to investigate how objects looted by the Nazis were acquired and, increasingly, objects taken under colonialism. As far as I know, there is no provenance research related to looting in the Cultural Revolution

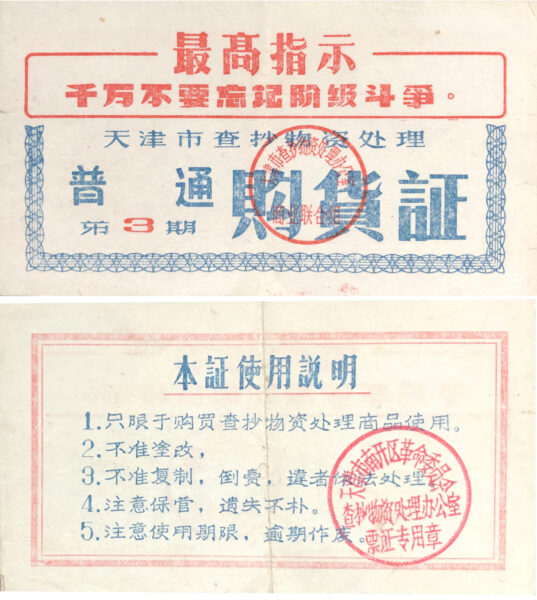

Most items were uninteresting to libraries, museums, or art collectors in China. Such items might instead have ended up in resale stores. The terms and conditions of the trade in confiscated goods were set by local governments. A rationing coupon from Tianjin reads:

- Can only be used for the purchase of commercial items from the handling of confiscated goods;

- Cannot be tampered with;

- Cannot be copied, resold; offenders will be punished according to the law;

- Keep safe, will not be replaced if lost;

- Take note of the validity period, invalid upon expiration.

The coupon was issued by the Tianjin Confiscated Goods Commercial Acquisition Group. This and other similar groups were responsible not only for setting the terms of trade in confiscated goods, but also for deciding how the items should be priced.

Strong similarities of procedure from one city to another suggest a high degree of coordination in the handling of confiscated goods from the start. As for the trade of seized items, the best we can do at this point is to say that it occurred. What the scope of this trade was, domestically and internationally, is still to be determined.

In some of the cases, possessions that were confiscated ended up being returned to their original owners, which is known as restitution. What did this process look like?

There has been very little research on restitution in the context of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. One of the primary reasons is that historians have assumed that restitution did not begin until after Mao’s death in 1976, when the Chinese Communist Party declared that the Cultural Revolution had been an error.

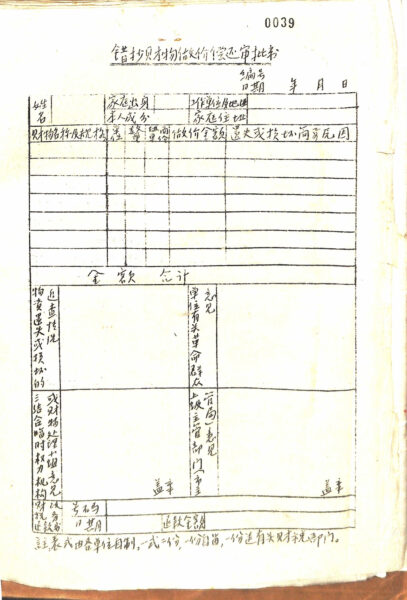

I have found instead that restitution began very soon after the raids, although it was limited. A form for approving the return of confiscated belongings, used in Shanghai in 1967, allows the owner to be identified not just by name and address, but also by their class status. The box for “class status” is significant because at this time, the Chinese Communist Party restricted restitution to those with a “good” class background, like workers and poor peasants. In one example from 1967, a Shanghai woman of “bourgeois” class was allowed access to her confiscated savings, but only because she was ill with cancer and needed to pay for her medicines. When bank officials discovered that she had also been given access to foreign currency, they determined that the request had been part of an enemy plot. Occurrences like this one were probably not common, but as long as restitution was framed in the language of class struggle, there was a certain risk associated with claiming one’s belongings. Over the next few years, the evaluation of who was — and who wasn’t — entitled to restitution changed.

How did the categories of who was entitled to restitution change?

Broadly speaking, we can identify two moments that expanded the scope of restitution. At both moments, the key question was who belonged among the People of the People’s Republic of China, by which I mean the members of the political community as opposed to the enemies of the revolution.

The first expansion began in 1969. This was when the mass mobilization phase of the Cultural Revolution ended. The Communist Party switched into a corrective mode, restoring some of the institutions and principles that had been disrupted in the earlier stage of the movement.

Around 1969, local governments began to extend restitution to members of the old elites: former government officials, religious leaders, capitalists, and intellectuals. These groups had enjoyed some protection from the Communist Party before 1966 but had become targets for the Red Guard attacks. A further push in this direction came in 1971, when Mao Zedong approved a recommendation to expand restitution to the old elites. This was a signal from the highest authority that these groups were no longer to be treated as enemies. Two years later, Shanghai had returned 56 percent of belongings seized from capitalist households. By 1975, this had increased to 70 percent — more than 33,000 households.

The second expansion came in 1978, at the beginning of the post-Mao reforms. Anyone who is familiar with the history of the People’s Republic of China will recognize this year as a watershed for class politics. The Communist Party ended most forms of class discrimination and described class as a historical category rather than a political label.

For restitution, this meant that anyone who had been affected by the house raids was, technically, eligible for restitution, regardless of class background. In practice, things were more complicated, as many belongings had been lost or damaged. Trickiest of all was the return of families to homes from which they had been evicted. Many disputes over housing continued well into the 2000s, and grew increasingly fraught when the price of real estate took off.

As you mentioned, this is a different way of thinking about restitution. How does this narrative of restitution processes change how we think about the Cultural Revolution and the period that came after it?

I would highlight two takeaways. The first is that we need to rethink the chronology of the Cultural Revolution, which is still thought of as a 10-year period starting with the Red Guard movement in 1966 and ending with Mao’s death in 1976.

Looting and restitution does not fit this framework. The ransacking of private homes only lasted for a few weeks in late summer of 1966. The loot remained in warehouses as the Cultural Revolution took a different direction, shifting focus from reactionary objects to revisionist tendencies within the Communist Party. But the loot did not stay there until 1976. My research shows how renewed efforts to reunite belongings with their owners after Mao’s death followed considerable initiatives at an earlier stage. Here, the watershed moment was not 1976 or 1978, but 1969, when the Cultural Revolution entered a less radical phase, and China started to improve relations with Japan, Hong Kong, and the United States.

The second has to do with our tendency to associate successful restitution efforts with strong property rights. I’m not sure how strong the connection really is. In the Chinese case, restitution seems to have been relatively successful, despite private property rights being virtually irrelevant both before and after Mao’s death. In 1987, the Supreme People’s Court issued an opinion stating that any case related to compensation for Cultural Revolution house raids should not be handled like an ordinary civil case, and should not be handled in court. In other words, the basis for restitution was not a legal right, but party policy. This meant that individuals had little recourse if the party denied their claim, yet the lack of property rights did not have a major impact on the overall scope or expediency of restitution. Logistics and politics were far more important.