In countries around the world, the “Green Revolution” has changed the scale and economy of growing crops, as pesticides, fertilizers, and new kinds of hybrid seeds have transformed the production process. In this episode of the Matrix Podcast, Julia Sizek spoke with two UC Berkeley scholars who study agrarian life in India, where farmers have been forced to adapt to changes in technology.

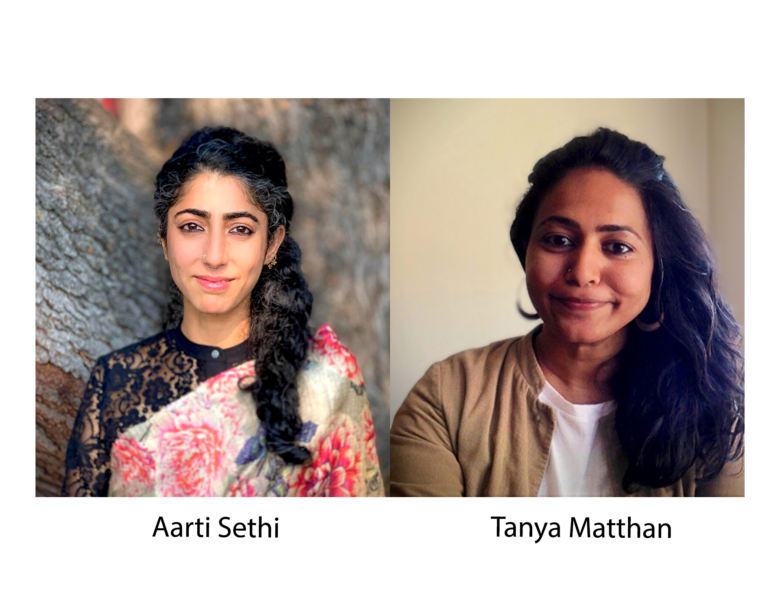

Aarti Sethi is Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at UC Berkeley. She is a socio-cultural anthropologist with primary interests in agrarian anthropology, political-economy, and the study of South Asia. Her book manuscript, Cotton Fever in Central India, examines cash-crop economies to understand how monetary debt undertaken for transgenic cotton-cultivation transforms intimate, social, and productive relations in rural society.

Tanya Matthan is a S.V. Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow in UC Berkeley’s Department of Geography. An economic anthropologist and political ecologist, she finished her PhD in Anthropology at UCLA in 2021. Her current book project, tentatively titled, The Monsoon and the Market: Economies of Risk in Rural India, examines experiences of and responses to agrarian uncertainty among farmers in central India.

Listen to the full podcast below or on Google Podcasts or Apple Podcasts. Visit the Matrix Podcast page for more episodes.

Podcast Transcript

Woman’s Voice: The Matrix Podcast is a production of Social Science Matrix, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of California, Berkeley.

Julia Sizek: Hello and welcome to the Matrix Podcast recorded with on campus recording partner, the Ethnic Studies Changemaker Studio. I’m your host, Julia Sizek. And today, our guests are Aarti Sethi and Tanya Matthan.

Tanya Matthan is a S.V Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow in Berkeley’s Department of Geography. An economic anthropologist and a political ecologist, she finished her PhD in anthropology at UCLA in 2021. Her current book project tentatively titled The Monsoon in the Market, Economies of Risk in Rural India, examines the experiences of and responses to agrarian uncertainty among farmers in Central India.

Aarti is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at Berkeley. She is a sociocultural anthropologist with primary interest in agrarian anthropology, political-economy, and the study of South Asia. Her book manuscript, Cotton Fever in Central India, examines cash crop economies to understand how monetary debt undertaken for transgenic cotton cultivation informs intimate, social and productive relations in rural society. Welcome on to the podcast.

Aarti Sethi: Thank you. I’m very happy to be here.

Tanya Matthan: Thanks so much for having us.

Sizek: So just to get started, both of you obviously study agriculture in India, but India has many different agricultural and ecological zones. Can you help us understand your research sites and how they fit into this broader agricultural production in India?

Matthan: Yeah, sure. I can get started. So the region in which I work is called Malwa, which is located in Central India in the state of Madhya Pradesh. So it’s a little bit northwest of where Aarti works in Vidarbha, which she’ll tell you about in a minute.

So the history of Malwa is interesting because prior to Indian independence, it was ruled by a number of princely states which were then carved together into this region, this political region of Madhya Pradesh, of which it is a part.

Ecologically, it’s a semi-arid region, and it’s known for its very fertile black soil. And it is also a region that has always been tied to global networks of trade and markets through the cultivation of crops such as cotton and opium in the past and now with soybean and wheat, which are grown for national and global markets. So ecologically, it’s a very interesting region different and similar to other parts of agrarian India.

Sethi: So as Tanya said, we work in regions that are actually both close by and also very far away because subcontinental India is agriculturally very diverse and also very vast. So I work in a region in East Central India called Vidarbha, and I tell people that it’s about 500 inwards from Bombay in the state of Maharashtra.

Vidarbha is again, it’s part of the central Deccan Plateau, so it has black soils. And cotton is a very, very old crop in Vidarbha. Now, the reason I found or find Vidarbha to be a very interesting region to understand agrarian capitalism or the long history of agrarian capitalism in India is because in Vidarbha local cotton production has been entangled with a global capitalist market, we could say first a colonial capitalist market, for a very long time.

So even though we have evidence for cotton cultivation in this region for three millennia but to take a more recent history, this is a region that became settled to the cash cropping of cotton after it was taken over by the British colonial state in the mid-19th century.

And this happens in the wake of the fall in global cotton production and supply in the wake of the American Civil War. So actually, there’s a very interesting historical relationship between Vidarbha and the American South. And at this moment is when the British colonial state expands what are called settlement operations and creates new villages.

And so there is actually a new peasantry that comes into this, what used to be agro-pastoral region, which is specifically cropping cotton for a colonial market. And so you can see in Vidarbha a peasantry that is entangled. And you can see this in its ritual forms, in the forms of land tenure that come into place.

We can say it’s early form and moment of agrarian capitalism. And that these processes that we see beginning in the late 19th century have a bearing on the cotton crisis in Vidarbha today. So that’s why I found Vidarbha and find Vidarbha very interesting place from which to view these processes. It is arid scrub agroecological region, which is very prone to droughts and it’s sort of rain-fed. And these are also the kind of agricultural– kind of ecological constraints within which agriculture in Vidarbha happens.

Sizek: So both of you alluded to the fact that agriculture is changing a lot today in India and that farmers are facing new challenges, which both of you study in different ways. Can you tell us a little bit about what those challenges are today?

Sethi: So the specific challenges that we see vis-a-vis cotton production in Vidarbha today have to do with the emergence of a sharp economy of indebtedness, which begins from the mid 1990s but over the next two decades becomes a very widespread mode of agriculture in Vidarbha. And this expansion of monetary debt as a critical component in the agricultural process in Vidarbha has had several economic and social consequences.

So one of the most tragic of them has been that Vidarbha is at the center and has been for the last two decades of a suicide epidemic, where over a quarter of a million farmers have taken their lives across India. This is not a crisis only focused on Vidarbha, but Vidarbha is one of the earliest regions where the suicide epidemic began. So Vidarbha become emblematic of a broader crisis in agriculture.

Now, the introduction of a new transgenic crop, Bt cotton, is at the heart– it is not the only reason, but its introduction has sharply exacerbated the general prolonged agrarian crisis in which India finds itself. So these are the broad contours, and I’m happy to talk a little bit more about this and the specificity of Bt cotton as we go further.

Matthan: Yeah, I think, Aarti laid out a lot of the central challenges of Indian agriculture now. And a place like Malwa also exhibits a lot of these same dimensions of this agrarian crisis. So you have, for instance, high levels of indebtedness, rising costs of production, extremely volatile prices of commodities.

And also ecologically, we can see in Malwa, the falling water tables for instance, which we’ll talk about later. So many aspects of this crisis are evident in a place like Malwa as well. But I also want to say that one of the reasons why I was interested in studying a region like Malwa, which is quite understudied in Indian agrarian history, is also because this region has been hailed as a recent agricultural growth story.

It’s emerging as horticultural hub for the production of these high value vegetables and so on. But it’s also very recently been a site of protest. So for instance, in 2018, six farmers were killed by the police as they were protesting unremunerative and crushingly low prices for their commodities.

And just to conclude, I will also say that one of the reasons why Malwa was interesting is because the state government has been at the fore of implementing and promoting a lot of risk management policies, so trying to address some of these challenges through things like crop insurance, price support schemes, and so on. So I was also interested in how the Indian state is responding to these agrarian challenges and with what social and ecological effects, so looking at the crisis and some responses to it and the implications of that.

Sizek: So this seems like an incredibly complicated story. We have, on the one hand, these debts that farmers are accruing, on another hand, these emerging forms of crop insurance that are presumably replacing other forms of government support that existed previously for farmers.

I just want to get a big picture of how this has shifted over time and since from the Green Revolution to today, how have the forms of support for farmers changed, and what are the reasons why farming has become so much more expensive to do?

Sethi: That’s a big question. So maybe I’ll break it up in terms of my answer. So if you look at cotton production over a recent historical, dure, let’s say, from the mid 19th century onwards, then we can say very broadly and this is broad, we can think of three phases of cotton production or pre-colonial economy of cotton, then a post-colonial economy of cotton, and a recent neoliberal economy of cotton.

So the Green Revolution is very central now in the imaginations of the post-colonial economy of cotton. But the Green Revolution has a variegated uptake across the country. So it’s first introduced in the northern states of Punjab and Haryana for wheat and rice as the primary or the emblematic Green Revolution crops.

And then this turn to science and technology has ancillary effects across the agrarian landscape. So when it comes to cotton, cotton is a crop, the improvement of which has a very long history in India beginning from the cotton improvement projects started by the colonial state. And this is because cotton is such an important fiber crop in India.

So one thing to remember is that the Green Revolution produces a certain kind of economy of agricultural production. It is an economy that is entirely, entirely reliant on state support. And through the Green Revolution, what you have is the state producing minimum price support for farmers, encouraging the use of chemical, and huge pesticide and fertilizer subsidies, electricity subsidies, and very importantly, a state scientific establishment that is heavily involved in the development of new hybrid and cotton varieties.

And this is a kind of public commitment that the postcolonial state undertakes towards agriculture in India. So part of these are things like the All India Cotton Coordinated Project, the establishment of 21 agricultural research universities, and the Central Institute of Cotton Research. And what the state does and scientists working in the scientific apparatus do at this time is take a very central role in developing new forms of seeds and through state extension mechanisms, getting those seeds to cultivators.

Why this is important is, and this is very important to the Bt cotton story, as we will see, is that it as through this moment of what we could call the Green Revolution, that the first hybrid cotton seed is created for the first time in India. And these hybrid seeds have a far greater yields than conventional cotton varieties. And this is the moment at which farmers who have access to large land holdings begin to adopt these new technologies and increase cotton yields and cotton production.

Now, this also comes with its problems, but the point I want to make is that the Green Revolution has a complex history in India. On the one hand, it introduces a industrialized, a non-capitalist, somewhat industrialized form of agricultural production, which increases yields. And on the other hand, it also produces an ecologically very, very vulnerable form of production that is dependent on high outlays. And this is the kind of stage that is then set for what comes later. So I’ll ask Tanya to now.

Matthan: Yeah, I think Aarti presented a really nuanced and compelling portrait of Green Revolution shifts in production. I only quickly add to that, which is to say that much of that story is a story of Malwa, but also to say that Malwa wasn’t an initial Green Revolution state.

So as Aarti mentioned, this was very geographically variegated. And Malwa was not a region that was considered for the introduction of these technologies. So it has a different history but with many similar effects over the last five decades or so.

What Malwa did see, which is analogous and parallel with and connected to the Green Revolution, was what is called the Yellow Revolution in the 1970s, and yellow referring to the color of soybeans. So as soybean cultivation was introduced and expanded, you see a huge number of transformations in agricultural production.

The displacement of crops such as cotton, sugarcane, sorghum, which were grown in this region, and a shift really to this industrialized model of agricultural production, which is built on monocropping, a huge capital intensive form of cultivation, input intensive cultivation, and so on. So even though it wasn’t directly impacted by the initial Green Revolution years, you see many of the same technologies and logics at work.

Sizek: And so the Green Revolution really helps to lay out how the government becomes intimately involved in the production of these crops. But today, a lot of farmers are protesting against the government. So what are the conditions that today– before when they were working more hand in hand with the government, with government supports, these same supports have been taken away. What’s changed?

Sethi: So what changed was the 1991 liberalization and the reforms. And these have had a huge impact on the way in which agriculture all over the country is actually impacted after the reforms phase. So many, many things change. One of the things that changes is prior to 1991, domestic agricultural markets are actually protected.

So if you look at cotton, for instance in Maharashtra, there is something called the monopoly procurement scheme for cotton where in order to buffer cultivators and increase the cultivation of cotton from the 1970s onwards all the way till 2002, the state was a monopoly procurer of cotton.

All the cotton that cotton cultivators produced could only be acquired by the state. And the state acquired all the cotton that cultivators produced. So you had a way in which import duties on fiber imports from other countries were very high and all of this changes in the post-reform period.

So 1800s agricultural products are brought under the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs. Import duties on agriculture that used to be up to 100% for certain crops fall to 30% in the space of like two or three years. And then the state, it raises rates on agricultural loans.

It withdraws from providing input, support, and infrastructural investment in irrigation and scientific research. There are upward revisions of the prices of diesel, of electricity, of petrol. And all of this precipitously raises the cost of cultivation on farmers without any change in the actual nature of production. So there is no increase in irrigation. There is no consolidation of land holdings.

And what you have is a widespread adoption of hybrid seeds, which on the one hand provide much more yield, but they are also very vulnerable to pest depredation. So from the 1990s onwards, agriculture all over the country enters a huge crisis and specifically cotton cultivation in Vidarbha.

Matthan: Yeah, I think just to add quickly to that and go back to Aarti’s earlier point, which is that the Green Revolution was only a success if it can be called a success at all because of the state supports. So what happens when the state supports are withdrawn? And you can see that in a range of arenas of agricultural production, whether it’s as, as Aarti mentioned, subsidies, agricultural extension service, so even the sockets of knowledge on which farmers depended now increasingly privatized.

And there’s less investment in agricultural infrastructures, whether that’s storage infrastructures or irrigation, and so on. So you really see since the 1990s a lot of the state support for agriculture on which this model depended really is taken away.

And alongside, I should also add that know, not only is the cost of production increasing alongside the removal of these subsidies and supports, but also so more broadly, the privatization of education, of health, and so on are also increasing the costs of social reproduction for agricultural households where they send their children to school, what kinds of health services they access, and so on. So you have this situation in which costs of production are rising while state support and investment is declining.

Sizek: And so this obviously has tangible effects for the people who are trying to continue to farm. And both of you actually did research with individual farmers, is involved sometimes being out there doing agricultural labor alongside them. Can you just give us an idea of what that looks like, especially since, as Aarti mentioned, a lot of these are still smallholder farms. They aren’t big industrial farms that we might imagine here in the American Midwest.

Sethi: Let me answer that question in two parts. One is to actually address what Bt cotton is. And I think that’s important because of the extraordinary change that that seed has produced economically, socially, and in terms of the labor regimes on the farm. So that’s why I think it’s important to just quickly touch on that, if I may.

So Bt cotton is a seed that has been genetically modified to resist predation from a certain class of pests, lepidopteran pests. This is the larva of the gray moth called the pink bollworm. And what Bt cotton is, is a TRANCE gene is inserted into the plant, and the plant becomes toxic to this larva. And when the larva chomps on the bollworm, it dies.

The justification for Bt cotton was that it offered a non-chemical solution to pesticide. And the reason that was important was, as I said, because of the introduction of these hybrid seeds which are highly vulnerable to pest attacks.

Now, Bt cotton as a technology has a very interesting relationship to the legal regime, which is that what Monsanto did was, it nested this technology into a hybrid seed which cannot be resown. See, all cotton grown everywhere in the world comes in two forms, something called hybrid cotton and something called straight line cotton.

Now straight line cotton, you save your seed this year, you preserve it, and you resow it the next year, and you plant it in density across a field. So this is where I mean a laboring regime. A farmer will plow that field and then dribble seed into furrows in the field and lots and lots of smaller plants are produced in a field.

What hybrid seeds do is you can’t resow them the next year. And so you are forced to buy that seed from the market. And the reason Monsanto did this was to protect its patent and its copyright. Well, not copyright, its patent. Let’s say its patent.

And so then hybrid seeds actually transform labor in a very big way. First, they require– fewer hybrid seeds are planted in a field. They need to branch and bowl. Secondly, they have to be fed large amounts of fertilizer and pesticide. This increases costs. Large amounts of fertilizer and pesticide actually also then produces huge amounts of weeds.

And so things like weeding, which would be done a few times, say, a season is now done continuously through a season. Weeding is a activity primarily conducted by women, so it has increased the participants– the labor days that women spend on a field.

Pesticide has to be sprayed very, very often because in fact, hybrid seeds foliage a lot. So all kinds of other pests get attracted, which means that men also now are involved in field labor in a different way. It means that women earn more income in their hands than they did earlier because they have access to this kind of continuous wage labor. But it also means that their forms of domestic labor have vastly increased.

So these are all the ways in which these new hybrid seeds and Bt cotton, besides the other social and economic costs, which I can talk about, also transform laboring relations between farmers and their fields.

Matthan: Yeah. To pick up on the question of labor in agricultural production, I think since I didn’t focus necessarily on one crop in the way that Aarti does with cotton, I found a slew of crops growing across the agricultural year, soybean, wheat, a range of vegetables.

And the rhythms of agriculture production change according to the crop and according to the season. But in the day to day, as, as Julia you mentioned, these are very small farms. The average landholding in a place like India is about, I think, 1 hectare, which is about 2 and 1/2 acres, extremely small farms.

A lot of the labor is done by people in the household alongside agricultural wage labor. And it changes based on the crop and based on the season. So across the agricultural year, you have various kinds of activities going on in the field from, as Aarti mentioned, weeding, which happens a lot more in the wake of these new seeds and crops to transplanting seedlings in the case of onions to long days of very difficult harvesting in the case of wheat.

So you have very different kinds of work being done in the field depending on the crop and the season. And I should also just add that even though a lot of my work, and I’m sure Aarti’s work involved going to fields and farms and working and talking to people in these spaces, the nature of farming is such that it also entails a lot of work in the home, for example.

There’s women who are cleaning seed in the home, are sorting produce in the home, and there’s a lot of work that happens in the home, in the market, and so on.

Sizek: So Tanya, you mentioned that so many of these different crops that people are growing, they’re being grown throughout the year. It’s not just one period of time. And they’re also highly dependent on rainfall on different climactic conditions. Can you tell us a little bit about how this has changed, and how it relates to the risk that farmers are taking when they’re participating in this market.

Matthan: Absolutely. So as I mentioned, there’s a range of crops that are central to agrarian life in a place like Malwa. So there’s soybean, which is the primary crop in the monsoon season, roughly between June and October. And then farmers move to growing a range of other crops, most predominantly wheat and gram, but also things like onions, potatoes, garlic have become increasingly important crops in this region.

So each of these crops has a range of different qualities ecologically, politically, economically, and so on. And so farmers are making a range of choices and decisions in deciding what to plant, how much to plant, and so on. So for instance, things like how long does this crop take to harvest?

So one reason soybean is still popular is because it’s a short duration crop. And certain varieties of seeds have been introduced in Malwa, which are extremely short duration. So within 80 days, you can harvest soybean, which allows you to then plant two or three more crop cycles on the same plot of land, which is really important to farmers who don’t have huge land parcels. So they can get more and more out of the same plot.

So just to go back to the question of how risk plays into this is that farmers are making calculations based on engagements with risk and uncertainty. So wheat, for instance, is an extremely water intensive crop. It requires irrigation, so you have to invest in irrigation.

But it’s also considered, for instance, a safe crop primarily because it can be sold at government procurement centers for a fixed price. So you don’t have to deal with the volatility of the market. You can just take your wheat at the end of the season, and you can be assured of a price. So it’s considered less risky.

Onions, for example, which is increasingly grown by farmers across class and caste in Malwa is seen as a risky crop. It requires a great deal of investment in inputs and in labor costs, but it’s also seen as very high yielding. And it’s risky because onions are incredibly price-volatile. In India especially, there’s huge price risks associated with growing onions.

So onion prices can shift dramatically within the span of days. And you could potentially garner huge profits, but also face crushing losses if prices crash. So this is just to say that there’s a range of risks and opportunities associated with different crops. And farmers are actually making a lot of careful calculations in deciding what to grow and how much to grow and when.

Sethi: I’ll just make a small because Tanya’s given us a very detailed thinking through this question of risk. One of the peculiar things, and actually not peculiar about the way in which risk is absorbed into a agricultural milieu, and I see this with cotton in a very intense form, is that cotton, post the introduction of genetically modified cotton, risk has acquired a valence in the agricultural milieu where on the one hand, cotton yields have vastly expanded.

So that is the potential of what you can reap from cotton is vastly expanded from the pre-hybrid economy of cotton but so have the risks associated with cotton cultivation.

And so the kind of calculations that farmers make is one where farmers both engage in this form of production and also find– it produces or has produced a sense of an everyday wearing stress. So people– this word tension, the English word tension has now become vernacularized into village speech.

And so beyond the economic risks, which are manifold, which a lot of people, scholars have written about that are discussed in the press, which is that cotton cultivation is economically really, really intense. It costs now 25,000 rupees. And the return on investment is very small. It’s about 3% to 5%.

So actually a farming family and again, all farming, 98% of farming is on irrigated. The monsoons are completely erratic. Every farmer has to make a calculation depending on how much debt you have, so how long you can hold on to cotton, how you can play the market. If you can store your cotton, you will get a higher price later in the buying season.

But if you are carrying a lot of debt for your seed cost, for your fertilizer cost, for your pesticide cost, you have to pay back that debt. And so a lot of small farmers will offload their cotton as soon as the sowing season and the cotton procurement season begins.

So risk is now both an operative emotion because we are finally talking about a personal relationship to this new kind of– no longer new with this economy of cotton and also economic fact of current agricultural production. And risk is operating at every level of the socioeconomic agricultural order. It is operating at the level of financial risk. It is operating at the level of climatic risk. It is operating at the level of failure of crop.

It is operating also through family relationships in a really intense way because everybody requires money to cultivate, and everybody requires– everyone is taking debt from everyone else. So people actually undertake debt within kinship networks. And so there is a kind of social and familial and risk in which social relations are also placed at risk, at risk of fraying.

Supposing you take a loan from your maternal uncle and you can’t pay back that loan in time, then that’s a family relation that has been placed at great risk. So that’s how I think one way to think of risk is to look at it in this kind of expanded sense is what I would add.

Matthan: Yeah, I think that’s absolutely right. And you’ve put it beautifully about how risk pervades. And I think maybe elsewhere you’ve said that risk is the structuring condition of agrarian life, and it permeates the economy but also intimate relations within family.

While I was interested in using risk as analytical lens into agrarian change, what I found was, just as Aarti mentioned with the use of the term tension, I also found that the term risk was used all the time in rural India. So everything was understood in terms of what is the risk of this. And people were using this term all the time to describe a range of activities and practices, not just in relation to farming but also beyond.

And as Aarti mentioned also, there are highly differentiated engagements with risk based on caste, class, gender, and many other kinds of calculations that go into how people are dealing with it.

Sizek: Thank you so much for your work, which is really revealed how agrarian life in India has changed with the introduction of these new crops over the last 50 years. And thanks for coming on the podcast.

Sethi: Thank you.

Matthan: Thanks so much for having us.

Woman’s Voice: Thank you for listening. To learn more about Social Science Matrix, please visit matrix.berkeley.edu.