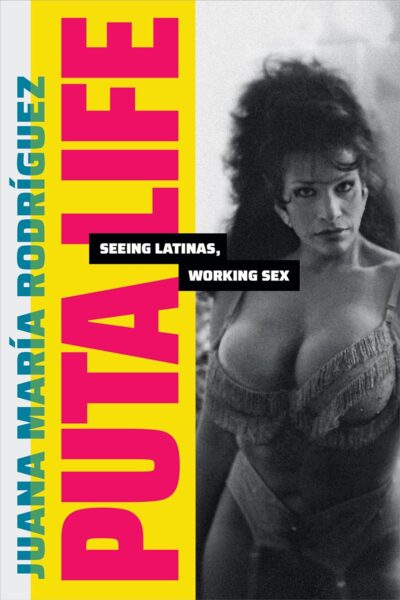

On Sept. 16, 2024, Social Science Matrix hosted an Authors Meet Critics panel focused on the book Puta Life: Seeing Latinas, Working Sex, by Juana María Rodríguez, Professor in the Department of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley.

In Puta Life, Juana María Rodríguez probes the ways that sexual labor and Latina sexuality become visual phenomena. Drawing on state archives, illustrated biographies, documentary films, photojournalistic essays, graphic novels, and digital spaces, she focuses on the figure of the puta—the whore, that phantasmatic figure of Latinized feminine excess.

Rodríguez’s eclectic archive features the faces and stories of women whose lives have been mediated by sex work’s stigmatization and criminalization—washerwomen and masked wrestlers, porn stars and sexiles. Rodríguez examines how visual tropes of racial and sexual deviance expose feminine subjects to misogyny and violence, attuning our gaze to how visual documentation shapes perceptions of sexual labor.

For this panel, Professor Rodriguez was joined in conversation by Clarissa Rojas, Associate Professor of Chicana/o Studies at UC Davis, and Courtney Desiree Morris, Associate Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at UC Berkeley. The discussion was moderated by Alberto Ledesma, Assistant Dean for Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity in the Division of Arts & Humanities at UC Berkeley.

The Social Science Matrix Authors Meet Critics book series features lively discussions about recently published books authored by social scientists at UC Berkeley. For each event, the author discusses the key arguments of their book with fellow scholars. The panel was co-sponsored by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, the Center for Race and Gender (CRG), the UC Berkeley Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, and the UC Berkeley Department of Ethnic Studies.

Watch the video on YouTube.

Listen to the panel as a podcast below or on Apple Podcasts.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[WOMAN’S VOICE] The Matrix Podcast is a production of Social Science Matrix, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of California, Berkeley.

[MARION FOURCADE] Hello, everyone. My name is Marion Fourcade, and I am the Director of Social Science Matrix. So if you don’t know us, Matrix is the flagship institute for the social sciences at Berkeley. Our purpose is to foster and to support exciting interdisciplinary collaborations and exchanges across the social sciences, like the exchange that you are about to hear today.

And for those of you who know us, you know that we have a lot of exciting stuff in store for you. So whether you’re interested in book panels, lectures, or conversations on today’s pressing issues, we have it.

I am especially delighted to open this semester with a panel discussion of Juana María Rodríguez’s book, published in 2023 by Duke University Press. Puta Life Seeing Latinas, Working Sex probes the visual representation of the figure of the “puta,” and how these representations have shaped the criminalization and stigmatization faced by sex workers. Juana María offers a masterful intersectional understanding of sexuality and sex work.

Today’s event is part of our Author Meets Critics series, which features critically engaged discussions about recent books by faculty and alumni in UC Berkeley’s Social Science Division. And I would be remiss not to mention that the talk today has a lot of co-sponsors. So I will list them all: the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, the Center for Race and Gender, the UC Berkeley Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, and the UC Berkeley Department of Ethnic Studies.

Now before I turn it over to our panelists, let me briefly mention our upcoming events for the fall semester. I cannot go over the entire program. We will be there for a long time. But I will mention a few immediate highlights. Tomorrow, we are hosting sociologist Jacob Faber for a talk on racial inequality in mortgage access as part of our collaboration with the NSF-funded working group on Computational Research for Equity in the Legal System.

On September 30, we’ll open our Matrix on Point series with a panel on hidden wars and open wars and geopolitical tensions in the world today. And that panel, which is very exciting, is titled “War is Back,” ominously.

And know that we will host three more Author Meets Critics panels this semester, featuring books by Paul Pierson and Eric Schickler, that’s October; Yan Long, in November; and Stephanie Canizales, in December. So we have much more. So please sign up for our newsletter.

But it is now time for me to introduce our moderator, Alberto. So Alberto Ledesma grew up in East Oakland and received his undergraduate and graduate degrees from Berkeley. He earned a PhD in Ethnic Studies in 1996, and is a former faculty member at California State University, Monterey Bay, and also a lecturer in Ethnic Studies at US Berkeley.

He has held several staff positions at Berkeley, including Director of Admissions at the School of Optometry, and Writing Program Coordinator at the Student Learning Center. He’s the author of the award-winning illustrated autobiography, Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer.

He is currently the Assistant Dean for Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity for the Division of Arts and Humanities here at Berkeley. So without further ado, I’ll turn it over to Alberto. Thank you all for being here.

[APPLAUSE]

[ALBERTO LEDESMA] Thank you. Thank you so much. And it’s really a pleasure to be here, everyone. It is great to be here in this Author Meets Critics panel on Puta Life: Seeing Latinas, Working Sex, by Professor Juana María Rodríguez.

As someone who has explored the themes of identity, marginalization, and the immigrant experience in my own work, I’m particularly excited to moderate this discussion. Professor Rodríguez’s book resonates with me deeply as it delves into the complex visual representations of Latina sexuality and labor, themes that intersect with my own explorations of undocumented experiences and cultural identity.

Like my illustrated work, Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer, Puta Life uses visual media to examine how marginalized communities are perceived and portrayed. Both of our works grapple with the ways in which societal perceptions and legal structures impact the lives of Latinx individuals.

While my focus has been on undocumented experiences, Professor Rodríguez turns the lens to the often stigmatized work of sex work and Latina sexuality. In doing so, she challenges dominant narratives and seeks to humanize those who are frequently dehumanized by society.

Puta Life draws from an impressively diverse array of sources. This interdisciplinary approach allows for a nuanced examination of how visual culture shapes our understanding of race, gender, and sexuality.

I am particularly intrigued by Professor Rodríguez’s exploration of how visual documentation influences perceptions of sexual labor. As we begin our discussion, I encourage all of us to consider how Puta Life pushes us to reconsider our perceptions, and opens up new avenues for more ethical forms of relation and care.

And so I am thrilled to introduce now the distinguished panel. Juana María Rodríguez is a cultural critic, public speaker, and award-winning author who writes about sexual cultures, racial politics, and the many tangled expressions of Latina identity.

As a professor of ethnic studies, gender and women’s studies, and performance studies at UC Berkeley, she is author of Puta Life Latinas, Working Sex, Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and other Latina Longings, and Queer Latinidad: Identity Practices, Discursive Spaces. Dr. Rodríguez was honored by the Center for Gay and Lesbian studies with the prestigious Kessler award in recognition of her significant lifelong contributions to the field of LGBT studies.

Courtney Desiree Morris is a visual, conceptual artist and associate professor of gender and women’s studies at UC Berkeley. She is a social anthropologist and author of To Defend this Sunrise, Black Women’s Activism and the Authoritarian Turn in Nicaragua, which examines how Black women activists have resisted historical and contemporary patterns of racialized state violence, economic exclusion, territorial dispossession, and political repression from the 19th century to the present.

Her work has been published in American Anthropologist, the Bulletin of Latin American Research, the Journal of Women, Gender, and Families of Color, Makeshift, Feminisms in Motion and Asterisk. She is a regular contributing writer and editor at large for Strangers Guide and ASME award winning magazine about place.

Clarissa Rojas is a scholar, activist, poet, mama, and movement maker. Her mother’s Indigenous lineages in the Americas root her in the Arizona Sonora Desert. Clarissa grew up in Mexicali, Calexico and San Diego, Chula Vista, where her family migrated.

She lives in Oakland, in unceded Huichin, and is faculty in Chicanx studies, cultural studies, and gender and sexuality studies at UC Davis. Clarissa co-founded Insight, and has authored and co-edited multiple articles, special issues, and books on violence and transformation of violence, including color of violence, the inside anthology, community accountability, emerging movements to transform violence, and most recently, her writing appears in the Journal of Lesbian Studies and Abolition Feminisms.

So with that, I want to invite Professor Rodríguez. Would you please start by sharing your insights and the genesis of the arguments in your book, please.

[JUANA MARIA RODRIGUEZ] OK. Again, thank you so much for coming. And especially to my interlocutors, it really — I chose wonderful people. Like so many other feminine subjects, by the time I became a teenager, I had already been warned about not dressing like a puta by my mother, hailed as a Spic slut by my schoolmates, ogled, pinched, groped, and treated as an object for somebody else’s pleasure by the adult men in my life.

In other words, I had already been assigned the category of puta by the world, and only had to decide my relationship to it.

As an academic who has created a reputation for herself as a scholar of sexuality, I’ve been rewarded in unexpected ways for writing, quite explicitly sometimes, about my own erotic archive, even as I have also been dismissed or excluded from other opportunities.

These two might be considered forms of sex work, ways of working sex that are pleasurable, profitable, and dangerous in different ways and to different degrees. The differences matter. While this project is invested in probing the slippery boundaries that define what constitutes both sex and labor, it is also committed to challenging the moral and legal hierarchies that are assigned to those differences.

Because while we might consider all the ways that sex could be exchanged for social status, dinner, citizenship, or domestic harmony and a good night’s sleep, exchanging sex for money remains illegal.

Illegal means you can be arrested just for doing your job — denied employment, housing, citizenship, and a host of other state benefits. A criminalized occupation means you can be more easily blackmailed or have your educational and career accomplishments tarnished, something that happens all the time.

It can jeopardize the custody of your child, or worse, your adult children can be arrested and charged with procurement or pimping if they benefit economically from your labor. It means you can have your assets seized or have your social media accounts shut down if you’re even suspected of engaging in illicit activities.

Today, the shadow bans and bank seizures being leveled against Palestinian activists were all first enacted on sex worker communities and their advocates. These are some of the current realities faced by sex workers in the United States, made even more obscene through laws such as SESTA-FOSTA.

Now as a project of intellectual inquiry poised between Saidiya Hartman’s ideas of critical fabulation and Glissant’s right to opacity, Puta Life tracks the figure of the Latina sex worker across a range of visual surfaces to consider how stigma sticks to skin. So after an introduction, I offer two historical chapters, and the first is focused on this singular text, Registro de Mujeres Publicas: registry of public women.

In 1865, Maximilian Archduke of Austria, established a public policy aimed at regulating sex work, which required them to have their name and photograph entered into this single bound folio. And already in this image, we can see that the photo in the top-left has been purposefully lifted out of the record by whoever had the access, audacity, or means.

This is Guadalupe Romero playfully offering the camera just the slightest hint of a coquettish smile, pose lifting the hem of her elegantly styled dress just enough to offer a visual clue of her vocation. So that gesture sort of gets repeated multiple times, but no one else does it quite as well as Lupita.

This is my tocaya, my namesake, Juana María, and she just looks sad. Here’s another Juana, Juana Rivera: 20 years old, seamstress. I found 19 Juanas and two Juana Marías. Her biography states that on the 22nd of April, she returned her booklet because she was leaving the profession.

And the police department is advised to keep her under surveillance, mandase vigilar. Juana Rivera was being kept under surveillance to ensure that she was not continuing to profit from her own sexual labor while trying to evade these new systems of control.

Several times, I find the phrases “se fugo,” she escaped, marking all the ways these women were sexual fugitives who tried to elude capture, tried to escape not sex work, but the state’s systems of sexual control.

Within the pages of Registro, I find another figure that sparks my queer curiosity, a name and a face that appears just a little different from all the others. Their name is Felix. As I continue to stare at this photograph, my eye settles on the stain, the punctum, the open wound where the surface of the photograph has been scratched away.

Felix’s dark wide hand rests gently next to that spot, touching it tenderly. I too wish to touch the open wounds these archives pry open to lovingly tend for the lives held within these bounded pages.

I also discover another queer gem in the archive. It seems that in 1888, in nearby Havana, Cuba, another metropolis, there existed a briefly lived political party of sex workers. They called themselves “las horizontales,” the horizontal ones.

And they used their newspaper, La Cebolla, to call out the sexual and economic extortion they experienced at the hands of the police and to demand their rights as taxpaying workers, the same demands being made by sex workers today.

And even in these four short issues, there are two references to homosexuality, including a heartwarming lesbian poem. Maybe I’ll read it at the end. But again, speaking to the way sex work and queerness have always sort of been bound together.

If that chapter is focused on a singular tome, the next historical chapter presents a broad, far-reaching set of images to reflect about on the visual motifs that get attached to sex workers, as well as to think about the different ways that sex workers appear in the visual record.

I start with Felix Jacques Antoine Moulin, who earned a month in jail and a fine of 100 francs for producing obscene images, like this one. Nevertheless, a few short years later, the same photographer was sent to colonial Algeria to document the queer practices of the new French colony. He spent quite a bit of time in brothels there.

This 1853 image, L’odalisque á l’esclave, exemplifies many of the visual elements that will continue to be associated with sex work. An attachment to ideas of the foreign and exotic, primitive opulence – that tiger print – forms of queerness, and a proximity to Blackness.

These images are from the Storyville archive in New Orleans. The woman on the left is Lulu White, one of Storyville’s most storied Madams. She specialized in octoroon beauties, like herself, at a time when miscegenation was still illegal and scandalous, demonstrating how race itself functioned as a sexual category.

But sex workers are all over the archives of street photography, travel photography, and what would become art photography. Frequently, images would be marked with a street location as a kind of geotracker pointing you to a foreign location or perhaps a distant, exotic neighborhood in your own city.

Because they were out in the street, photographers viewed sex workers as free models, public women they didn’t have to pay for, but whose images they felt entitled to capture. In fact, sex workers show up in the camera rolls of almost every noted photographer, male and female.

This is an image from Eve Arnold. And it initially appeared in Esquire Magazine in an article titled “Havana, the Sexiest City in the World.” But it also marks the moment when photographers could begin to own and label their own photographs, which Arnold renamed as “Bargirl in a Brothel in the Red Light District.” So Cuba actually falls out of that scene.

Part of what I started to notice is that whenever Black sex workers are depicted, they are almost always framed within the terms of tragedy, regardless of class. She’s beautifully dressed. Here’s an image from the series titled simply “Séríe Prostitutas” by the Colombian photography Fresnel Franco.

And we get a series of images that are supposed to register sadness and despair. The photographer here can’t imagine that she might have a life outside of her work. She might have kids she plays with, or a husband she goes to the beach with. It’s about reducing her to the space and place of her labor. It is intended to represent only and always despair.

However, this project started with a very different text. It started in the porn archive, with an as-told-to-memoir that depicts the life, sexuality, and philosophical musings of one of my most cherished Puta icons, Vanessa Del Rio. She follows me on Twitter. The most famous person, yes.

Half Cuban, half Puerto Rican, and fully a New Yorker, Vanessa Del Rio was the first non-White porn star during the golden age of porn. She appeared in hundreds of films, frequently playing the maid, the hoochie mama, the stereotypic over-the-top Latina spitfire.

Her memoir, unique in both form and content, is a huge tome, it weighs about 7 pounds, that comes complete with a DVD made up of equal parts hardcore pornographic images, and titillating and terrifying life stories, many about police violence.

But if you want the porn, you have to sit through the stories. And if you want the stories, you have to sit through the porn. And unlike the silent presence of the women in El Registro, here we have the vibrant voice of one of the most celebrated Latina sex symbols, providing her own musings on Puta Life.

I grew up watching Vanessa’s films. And her birth name, Ana Maria, is a sonic echo of my own. While the rest of the book is full of glossy movie posters and professional stills from her many films and colorful magazine spreads, the photographs that intrigued me the most were the ones from the collection of amateur photographs that she produced with her lover, an S&M aficionado, Reb Stout, pictured here in a blonde wig.

Del Rio describes her initial coming together with Stout saying, it was like you like to wear makeup and women’s clothes and stick dildos up your ass and jerk off and take pictures. OK. Yeah. Many of these images are quite playful and queer, and depict the spirit of endless sexual experimentation that their brief affair was founded upon.

Several portray enactments of the S&M fantasies that Stout and Del Rio explored and performed together. As an actor, Vanessa was involved in many hardcore S&M themed movies, “roughies” as they were called. And she describes enjoying the emotional intensity and physical stamina that they required.

This scene is from the film Top Secret, in which she plays a secret agent named Juanita, who is being tortured, yet her makeup flawless. But the scenes she shared with Stout were something else altogether, and the images that they produced have a wholly different quality. That chapter also includes this quite extraordinary image, one that manages to convey the terror, vulnerability, and ecstasy of sexual submission.

Vanessa tells us that this is her favorite image in the book. It’s also my favorite image in her book. This too is Puta Life, a moment where the everyday pressures associated with living your sexuality in public are transformed into private experiments with the sensorial possibilities found at the limits of subjection.

If Vanessa’s life as an international pornstar offers a view of sex work that seems full of fiery agency and verve, the following chapter returns us to the streets of Mexico City to visit with the extraordinary women of Casa Xochiquetzal, a house for elderly sex workers, some retired, most not, to think about the relationship between the stories we tell and the affects they generate.

The residents of Casa Xochiquetzal are the subject of two books of photography, numerous photo exhibits and magazine spreads, and at least three documentaries, illustrating the fascination with the decidedly queer juxtaposition between advanced age and overt sexuality.

The first book, Las Amorosas Mas Bravas, was a collaboration between French photographer Benedict de Ruz and Mexican journalist Celia Gomez Ramos. That project took about seven years to complete, and as viewers, we get an almost voyeuristic glimpse into this house and their lives.

This is Canela. We’re introduced to Canela’s story, and the journalist reveals that she has Downs Syndrome. Quote, “She’s a little slow, but the girls never talk about that,” end quote. And we’re told that she’s just returned to Casa Xochiquetzal after trying to give love one more chance at 72.

Like her age, Canela’s cognitive difference is supposed to make her an unimaginable subject of love, sex, or indeed of any future worth desiring. But where exactly might we locate the tragedy that is represented as surrounding Canela’s life? In her lifelong disability, in the innumerable ways that precarity brought about by poverty has informed her life choices, or in trying to give love one more chance at 72?

Moreover, how might the narrative emphasis on tragedy obscure the moments of pleasure — sexual, romantic, and otherwise – that might also constitute her life? What are the effective impacts of these different sorts of details, and whose interests do they serve?

This is another resident, Norma, and pages later, she recounts the story of her life through the scars left behind: The stab wounds from knife fights, the scars from suicide attempts, a bite mark, a souvenir from her lover, Rosa.

Norma tells us that she’s a womanizer, a mujeriega, and that she once worked as a lucha libre wrestler, that the father of her firstborn was a travesti named Arturo, also known as Erica. She lists off a long list of female lovers, including Rosa, who was her girlfriend for 13 years and who she would pimp and protect when they both worked the streets. Norma says she’s too tired for women these days. Is Norma who we picture when we think of sex workers or pimps?

There’s a second book of photography that pairs a foreign photographer and a Mexican journalist. This is British photographer Malcolm Venville’s book, The Women of Casa X, that similarly provide brief first person narratives composed by Mexican journalist Amanda de La Rosa.

That book was produced in a single month, and frequently features the women in various states of undress, unsettling the conventions around erotic photography. In both books, these women talk about their lives, including the violence, exploitation, and abuse that they’ve lived through.

But what their stories make abundantly clear is that the harms associated with sex work cannot be separated from the violence of patriarchy, global capitalism, the church, the state, the police, the family.

I also consider several documentaries about the house. This is La Munéca Fea. I just love this cover image. But I focus on a truly delightful film by Mexican photographer and filmmaker Maya Goded that registers a wholly different energy, not of misery and despair, although that comes through, but the felt force of friendship. The film is called La Plaza de la Soledad. And we see the kind of mutual aid and kinship that sex workers have always formed.

The woman on the right is Carmen Lopez, the original founder of the house. And in this scene, she spots one of her clients and is joking about what she’s going to do with her little finger once they get together.

Goded’s relationship with Carmen spans over 20 years. Goded helped Carmen activate the feminist community in Mexico City to fund Casa Xochiquetzal. The film also features a lesbian relationship between Esther, an Indigenous woman and healer, and her lover, Angeles.

Esther often delivers these very touching monologues about what is unseen in the lives of these women. But thankfully, neither Goded nor Esther seems particularly invested in peddling a romantic narrative about idealized lesbian relationships.

In a later scene, the couple are playfully bickering over money and drugs. And Esther positions herself in front of Goded’s camera, while Angeles finishes getting dressed nearby to tell us what their lover squabble was really about.

[NON-ENGLISH]. Yesterday she hit me. She took my money. And later, we ended up fucking. Esther, always pedagogical in her addresses, adds to the camera, but I enjoyed it very much sexually. Everyone is laughing, including Goded, whose image is now captured in the mirror along with a glimpse of Angeles getting dressed nearby.

These moments where the director enters the scene aurally or visually serve to dislodge the imagined distance between the filmmaker and her subject. But what also becomes dislodged are more sanitized ideas about lesbian sexuality, Indigenous identity, sex worker lives, and feminist politics.

So while my work in this book is about sex work and all of the ways that it’s wrapped through the contours of queer life, it’s also about representation, about the perilous ways it can carry our desire for recognition and connection across the vast expanses between us.

Because even if we know that images and stories are mediated and constructed, we know they do things in the world. And while I have never met most of the women that I feature in Puta Life, in the final chapter, I turn to someone quite dear to me, Adela Vazquez, a real living person with a style, a scent, and an amazing past.

I begin by considering the text Sexile, Sexilio, an extraordinary bilingual graphic novel by Jaime Cortez that tells the story of Adela’s life of being assigned male at birth in Cuba, forming part of the Mariel boatlift, and working briefly as a sex worker, later becoming a sexual health educator and transgender advocate in San Francisco.

As is the case for most people, Vasquez worked as a sex worker only briefly, although the different narratives circulating around her life make clear she’s been working sex all her life. In this top panel, we actually see the actual ad that Adela used to promote her sexual services.

But by the time we sort of reach the bottom-right panel, Cortez draws her, rolling her eyes and we glimpse her boredom and frustration at performing the tired narrative of racialized transgender exoticism.

Now, Sexilio is not the only graphic account of Adela’s life. I first met Adela when we worked together at Proyecto ContraSIDA Por Vida, a Latinx HIV Prevention Agency in San Francisco. And I featured her in my first book, Queer Latinidad. A year later, she appeared in the documentary, Documenting Difference, in 2004.

Adela’s trans godchild and my former student here at Berkeley, Juliana Delgado Lopera, published an oral history of Adela, first in the SF Weekly and later in the Collection Cuéntamelo. Here, the arch of her eyebrow is performing its own singular drama.

She’s also featured in the collection Queer Brown Voices, personal narratives of Latinx LGBT activists. And in one class I taught, students read Sexilio and created a Wikipedia page for Adela because nothing says notable like having a Wikipedia page.

But despite these numerous efforts at representing her extraordinary life, Adela, like many of us, is also deeply invested in self-representation. And what better place to share ourselves these days than social media. Adela’s Facebook page does not disappoint.

While her feed is cluttered with the usual collection of political rants and raves, Adela also maintains a photo album there that she’s entitled, The Amazing Past, a visual archive of her larger than life history. Here she is, strutting her stuff for the camera and her audience.

This is Esta Noche, a broke down dive queer Latinx bar, the last queer Latinx bar to close in San Francisco. Some images like these have been digitized from actual printed photographs, and some include captions added through the haze of memory.

All of these efforts at curating her life, serve as a testament to her impulse to give her memories, material substance, even if that substance is digital. Yet even in the presence of the biographical subject, even if Adela was here with us now representing herself, we wouldn’t really know her. Not really.

And that’s as it should be. As we refuse the understandings of representation as knowledge production, a lingering and feeling in friendship, in the fantasy of another world, might point us to other affective pathways of care.

Let me conclude by sharing another photograph from Facebook, a candid photo of Adela from her days at Proyecto ContraSIDA smiling at whoever stopped by with the camera to interrupt her day. Adela was very good at her job, and is rightfully proud of the life changing work she did at Proyecto, recruiting other trans Latinas, many former sex workers like herself to protect themselves against HIV.

But also inviting them to form part of a community dedicated to living to self and community empowerment. But this photo of Adela also makes another point undeniably clear. Trans women, particularly trans women of color, need more than representation.

They need jobs that provide health insurance and employment protection, sick days, and vacation times. Indeed, a job like my own that offers a pension so that one day they can stop working. Similarly, sex workers and former sex workers don’t need rescue. They need rights to live free from stigma, surveillance, and criminalization.

In the absence of these most basic forms of care, our new gender studies colleague, Dora– the brazilianist, Dora Santana, describes the practices of survival and community formed within Black trans femme spaces of impossibility, a practice she calls mais viva, more alive. Mais viva, quote, “the strategies we as trans and Black people use to not be broken at the end of the ” end quote.

But mais viva also demands mass viva, more life. Santana’s invocation of mais viva serves to remind us that survival is always more than protection from physical harm. It is about attending to the weight of a world intent on denying the beauty of your humanity and the psychic scars that stigma leaves behind.

Today, sex workers face a worldwide epidemic of violence and murder. Sex workers are routinely hunted and harmed by those who understand that the value of their lives is deemed negligible, insufficient to warrant concern, let alone protection or justice.

Therefore, my work in this new book also harbors another meaning for Puta Life as a response to Puta viva, a fucking life, a life defined by condemnation, violence, and stigmatized contempt, I offer the possibility of Puta Life, an affirmation of the beauty, value and spirit of Putas everywhere. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

[ALBERTO LEDESMA] Thank you so much, Professor Rodríguez. Now I invite Professor Morris, please, to share your comments.

[COURTNEY DESIREE MORRIS] Thank you for that. That was fantastic. It’s so good to be here. It’s rare to enjoy reading an academic book as much as I enjoyed reading this book. And don’t get me wrong, I love theory for the same reason. I love couture.

But this is really an extraordinarily powerful work. And so brilliant that it left me kind of speechless. And one of the things that Clarissa and I were talking about was how the text really, it didn’t raise questions for me about the way you approach the work, but it did raise questions for me about myself as a reader, as a scholar, as an artist, as an erotic subject that I really was not prepared for.

So I just wanted to talk more about that. But I’m going to get into my comments here, and I’m looking forward to being in conversation with you about this work that really is just such a triumph. Congratulations. Yeah.

So I’m going to begin by saying in Puta Life, Seeing Latinas Working Sex, Juana Rodríguez invites us to examine the contentious and fraught production of visual representations of the Puta, sexual labor, and Latina sexuality.

Centering the modes of self-fashioning of Latina sex workers across visual cultures, Rodríguez illustrates how insurgent Puta lives are made in the interstices of quote, “crimanalizing states and the judgments of petit publics, ” end quote.

Telling a different story about Puta Life requires different modes of relationality and methodology than the traditional Western mono disciplines can provide. Thus, Puta Life employs an interdisciplinary methodology ranging from exploring the role of photography as a tool of 19th century colonial statecraft to close textual readings of sex workers’ visual and narrative biographical accounts of themselves to, quote, “explore the creation of sexual meaning and what might lie beyond it,” end quote.

Drawing from state archives, historical and contemporary documentary film and photography, biography, visual art, and graphic novels, Rodriguez creates a promiscuous archive of pouteria that is born out of a deep identification with the figure of the Puta, and that also reflects her own erotic subjectivity as much as that of her research subjects, which I thought was the best part.

The analytical objects that she selects from this archive are varied and wide ranging, selected not for the authoritative power that they confer to render a grand narrative of Puta Life, but rather for the haptic resonances that they present to Rodríguez as both researcher and subject.

The politics of identification that structure the text are felt in Rodríguez’s careful and effective handling of the subjects that she encounters in the archive. And so I won’t rehash the discussion of the Registro, but I was really struck by the way that you talk about and you examine how the Maximilian state mobilized photography as an emerging visual technology of state surveillance, criminalization, and labor regulation.

She sifts through this visual archive, attempting to understand how women navigated this hierarchical system of organizing sexual labor, and how the politics of race, class, and nation shaped the state’s management of sex workers.

And I was particularly moved in the portions of the chapter where you talk about encountering women who bear your name in the Registro, your [NON-ENGLISH] and this experience of encountering your name over and over in the archive. Rodríguez writes tenderly of her, tokayas asking, quote, “did Juana María also dream of adventure and freedom? Did my tokaya taste joy.”

This kind of speculative narrative, what Saidiya Hartman refers to as critical fabulation, the attempt to read beyond what the photograph or the archive itself can yield, the attempt to touch an unknowable past that wears your face or bears your name unsettles historical narratives of the Puta that mark her as unknowable political subject, and calls for rigorous forms of care and archival inquiry.

This is also apparent in the treatment of Félix, who I love this figure, and I just sat staring at this photo for what felt like forever. And so looking at Félix and their ambiguous gender presentation, which is left unaddressed and unresolved in the archive, right? It doesn’t offer you a clear answer of who this person is. And so rather than rush to claim Félix as a trans ancestor, a move that I think probably would have been really satisfying for many of us.

Instead, you embrace the incompleteness and indeterminacy of the image itself, and the space that it allows for, quote, “an imagined queer futurity,” end quote, where Félix and all of the subjects of the Registro are able to, quote, “escape the vice grip of representation to become fugitive traces of the images left behind to no care.” So beautiful.

In this way, I see Rodríguez performing a kind of radical feminist self-reflexivity rooted in an ethics of accountability and answerability to her subjects, past and present. In addition to its analytical function, Juana frames Puta Life as a pedagogical text that invites us to take seriously what the Puta can teach us, not just about our own erotic desires and selves, but also about the larger structures of power that police and discipline are desires.

It reveals the ways that we are all implicated and implicated in Puta Life, often in ways that we may be reluctant to explore because they compel us to reckon with the complexities of our own lives and the exploitative sense. Deal with your own fucking life.

This kind of analytical humility, a willingness to approach the Puta, a figure that we think we know from a place of beginner’s mind and embodied experience, opens a range of complex and contradictory possibilities for how we might sense the Puta in a different register. And it certainly did that for me as an artist.

And I’d love to have more of a conversation about this as a kind of embodied text, as a thinking about the ways that you tap into the body as a way of beginning to sense the Puta. And you talk about the importance of sensing knowledge rather than thinking, which I found really interesting.

I found this to be a work of profound vulnerability and beauty, characterized by, as Judith Butler writes, a willingness to be undone by the encounter with the research subjects, with the Puta within and without.

This is especially apparent in Rodríguez’s reflection on aging and the labor of sex work. And I thought about this a lot in the chapters on Vanessa Del Rio with Adela and with the women of the [NON-ENGLISH], and how Latina sex workers of many kinds navigate the challenges of working in a sexualized economy of value and desire that privileges youth beauty in class while obscuring the labors, the sexual labors of elderly and retired sex workers.

And I was really struck by the way that you write so movingly about seeing yourself reflected in these aging sex workers and how you and all of us, we’re all getting older, how we navigate the tensions between our ageless desires, as you say, and getting older in a social order that disappears the sexual lives, labors, and subjectivity of elders.

Another indication of your practices as a kind of vulnerable observer, as Ruth Bejar might say, is the way that you assume an intentionally ambivalent sort of narrative orientation towards both yourself as researcher and subject, as well as your research subject, and the contradictions inherent in any attempt to render a subject legible.

As you argue, quote, “whether as a photographer or a writer, to think about representation is to think about the granting of permission, the stated or unstated permission to look, to linger, to record, to circulate, and to transform the meanings that images might convey.”

These tensions over who has the power to narrate, which we’re going to talk a little bit more about in a second, form a central preoccupation in the text that I really think adds to its analytical force. Nowhere is this felt more clearly than in the chapter on the mighty Vanessa Del Rio, one of my longtime heroes.

I’ve been fascinated with her for years. And your treatment of how she narrates her Puta Life on and off screen demonstrates how a more textured and complex rendering of Puta Life, quote, “requires that we wrestle with the ability of speaking subjects to narrate their own complex realities even and especially when their interpretations unsettle the preexisting logics we might wish to impose.”

You offer a model for meaningfully engaging with research subjects who dazzle us, who confound us, who baffle us. Writing that, quote, “this is a lesson that bears repeating. Not everything makes sense.” End quote.

And indeed, as you argue, the truth of our erotic lives often does not make sense. And yet it is precisely in our illegible desires that the future conditions for queer horizons of possibility that have not yet been borne may materialize.

And I was thinking a lot as I was preparing for this talk, I listened to a really terrific interview that you gave about the book on the LA Review of Books podcast, and I thought i it was a really thoughtful and interesting interview.

But nevertheless, I was struck by what seemed to me to be a kind of moral uneasiness or discomfort or kind of squeamishness about the attempt to narrate Puta Lives at all. And the implication seems to be that Puta Life is so complex and so overdetermined and so distorted as to be fundamentally unrepresentable, or that all acts of representation do a kind of inherent violence to these lives.

And that kind of pushback that I’ve certainly had that experience in my own attempts to teach sex work in the classroom. And it seems like you have encountered some of this in the reception of the book as well. And so I’d love to hear you talk more about that.

But they illustrate how Puta Lives are obscured not only by official state discourse that marks sex workers as moral or social threat or hapless victims, but also by ostensibly progressive or radical feminist frameworks that are so weary of the punitive uses to which narrative can be put that they refuse the work of narration altogether.

And so, as you demonstrate, this is really an untenable position that in effect ends up relegating Puta Life to the criminal margins in ways that threaten sex workers and make the conditions of their labor precarious.

And so I think you really definitely negotiate that critique with a keen awareness of the dangers and challenges of representation, and how visual regimes of racialized sex and gender, knowing that render the lives and labors of sex workers illegible in the public sphere operate.

And so instead of making a claim to epistemic transparency, you follow the work of the Martinican philosopher Edouard Glissant by insisting on the right of sex workers to their own forms of opacity. And as a scholar, you refuse the kind of will to knowledge that underwrites normative representations of the Puta, while insisting on the need for these lives to be seen and narrated.

And then the last thing I’ll say is I was really struck by– throughout the book, there’s this kind of thread of queer femme friendship that for me really is kind of the condition of possibility for the work. And I felt that so clearly in the chapters on Vanessa and on Adela.

And it made me think of Michel Foucault’s interview, friendship as a way of life, in which he talks about sexuality functioning as quote, “a means not to discover the truth of one’s sex, but rather to use one’s sexuality to arrive at a multiplicity of relationships.” And so friendship here functions as both a method of seeing and being in the world.

And so following Foucault, I see Puta Life as countering the refusal to explore, quote, “everything that can be troubling and affection, tenderness, fidelity, camaraderie, and companionship, things that a rather sanitized society can’t allow a place for without fearing the formation of new alliances and the tying together of unseen lines of force.” So I see all unseen lines of force kind of cohering in the text and these really beautiful ways.

These unruly and promiscuous forms of relationality reveal a different mode of life, as Foucault argues, or a different mode of relationality cultivated through sexual practice that brings us into organic forms of what Samuel Delaney terms contact and exchange, both those that are tied to the market and others that exceed the market, which are constrained under heteronormative regimes of marriage, domesticity, family, and the rule of the father.

And so I was touched very deeply by Adela’s response to that chapter where she says very simply, [NON-ENGLISH]. It is a very sweet, deeply affecting, and instructive moment. For while, Rodríguez powerfully makes the case for the singular importance of Adela’s trans everything life. We also understand that this is one interpretation of her life among many others.

There could never be enough to say about Adela’s complex biography, and no one could ever transparently know Adela. But that is no less true of all of us. And the extension of what Avery Gordon terms complex personhood to our inscrutable research interlocutors is the first step in telling stories about Puta Life that might take us closer to an embodied affective sense of the multitudinous cells that are contained within Puta biographies of all kinds, including our own.

[ALBERTO LEDESMA] Thank you so much. Professor Morris, that’s fantastic. So now I invite Professor Rojas to please offer your notes.

[CLARISSA ROJAS] I enjoyed this so much. Thank you both. This is just so, so lovely. And obviously, the text, I agree, moved me in ways that I was not ready for nor expected from an academic text. And I think some of that has to do with the methods you choose, the style of writing. And so I’ll speak to some of that as well. And it engaged a kind of playful engagement that I think in some ways my remarks will also engage that or reflect.

So dear Juana, if your plight in Puta Life was that we fall in love with, that we see the life in the Puta in you, the Puta in ourselves and Putas everywhere, then you have succeeded because Puta Life, testament of a visual and historical archive of Puta Life, living and legacy against a script of erasure, victimization, and exoticized exteriority inspires just that.

How lovingly your writing, and I guess we all concur here, made me see perhaps my ancestor Felix Rojas. The details of Felix’s life in a portrait, the subject leaps from the abject captivity of the two dimensional springing forth, a deep curiosity in life worth knowing. Who was Felix Rojas?

A subject like the others, like the author herself, with a quest to be loved, touched, adored. it is in these moments of candid, introspective memoir that the author reveals her vulnerability, dislodging academic treatise and methods returning to intimate aspirations.

Quote, “these women speak to me because I know they have something to teach me about the realities of my Puta Life. Their faces and their stories obligate me to sit with emotions that I might wish to expel, to ponder my own relationship, to living and aging, desire, and rejection, loneliness, and heartbreak. To dwell in the dusk of my own archives of feeling.” End quote.

After all, at the heart of this book is a quest to make Puta Life more livable for all of us. And to do just that Juana shapeshifts method, Puta Life asserts a knowledge production that is at ease and unknowing and a methodological reckoning with unruly practices of sensation, memory, and imagination.

The sensory drives after all this, the project of a struggle for corporal autonomy. The social transformation beckoned by Puta Life. Against the grain of a historical subject that is stigmatized, criminalized, controlled, disappeared, despised as much for their race and poverty as their sex work, in quote, “their humanity obliterated.”

So the word Puta, writes Juana, quote, “I add life, the possibility of a life that will exceed the word and remake it.” End quote. Juana invites the reader to reach for the traces of felt possibility that might inspire more ethical forms of relation and care.

And today is [NON-ENGLISH]. No school or work, a holiday in Mi Patria Natal in Mexico. A day to remember the call to revolutionary struggle that upended the Spanish colonial regime and imagined a new republic and the masses flocked to El Zocalo and city squares everywhere to memorialize El Cura Criollo Hidalgo’s call once made in 1810 in the town of Dolores.

Yes, it is in the genealogy of this memorialization that the park marking queer beach and Dyke and trans marches in San Francisco gets its name, Dolores Park. And as the call for liberation imagines anew the republic anchored in the patriarch of the nation, forgotten feminicidios, unnamed just this once, the Traidora Puta Malinche reclaimed by Chicana feminists as lover, mother, freedom seeker, once enslaved, brilliant translator.

Instead today, the nation invokes yet again a future promise of the Mexican nation as liberated from Spain by Spain, the Criollo masculine subject of Hidalgo, a rendering of the neocolonial patriarchal Mexican imaginary.

Not the reference I prefer of thousands of feminists descending in 2019 in El Zocalo to the cadence of [NON-ENGLISH], the oppressive state is a sexist pig.

So it is fitting that we address the subject of the Puta today. After all, what the Puta [NON-ENGLISH] invoking, of course, Frederick Douglass’ interrogation. And further, what the Palestinian [NON-ENGLISH].

So I walk with Palestine at the center. The recent massacre [NON-ENGLISH] last week, beloved land I visited over 20 years ago, amidst yesterday’s death of a brilliant scholar and writer, Elias Khoury, who mapped the future of Palestinian freedom in his epic [NON-ENGLISH], gate of the sun, which he brought to UC Berkeley in this very building 18 years ago when I had the chance to meet and learn from him and his work.

As a daily death counts persist, how can we not center Palestine? And what I ask can be learned from and about Puta Life, about the liberation of both Putas and Palestine in conversation.

How does mapping, writing, imagining Puta Libre accompany mapping, writing, imagining, and struggling for Palestine Libre. Juana invites us to consider “que todos/todas somos putas” . The Zapatistas once invited us to proclaim [NON-ENGLISH] Zapatistas to return the dislodged expelled Indian in us as Chicanas and Mexicanas.

To commit to a futurity that liberated the Indigenous from the continual colonial claws of the neocolonial Mexican Republic [NON-ENGLISH] Palestines. So [NON-ENGLISH] Juana, I offer some excerpts of Puta Life in conversation with Noura Erekat’s justice for some law and the question of Palestine. And Edward Said’s the question of Palestine, among other Palestinian voices.

And why Noura Erekat’s text so centrally? Because the National Leadership of Faculty for Justice in Palestine recommends it as one of the five essential texts to read this fall to inform the Palestinian struggle across college campuses. You can join one of the 125 FJP chapters across the US to further engage this text. And Noura is no less also a UC Berkeley alumni from the Bay.

Long-term sister organizer, now professor of law at Rutgers, a foundational member to the originating second formation of Students for Justice in Palestine here at Cal, where SJP was born some 30 years ago. And organizer of the first National Student Conference of the Palestine Solidarity Movement in the United States, which I attended also here 22 years ago during the Second Intifada.

One, Puta Life. In their ongoing demands for love, respect, and care, these women of [NON-ENGLISH] remind us all the ways we are entangled in the radiance of the universe, united in our stubborn insistence to live on. Stigma, conditions, the life, and death of sex workers.

Three, the call for self-determination upends the eliminatory logic that for so long has marked the Palestinian as a site of expendability. Justice for some. Puta Life. Native presence, survival as resistance, acknowledge presence in the face of social demands to disappear.

Five, Puta Life. Vanessa Del Rio and Adela Vasquez turned victimization into expansive narratives of sexual prowess. Quote, “Venessa Del Rio is invested in asserting more than her agency, wants to describe her pleasure, the joy and satisfaction of sexual escapades. Del Rio refuses to vanish to either feminist narratives of exploitation, shamelessly relishes the dirty sensory Puta Life.

Six, justice for some. Palestinian self-determination signifies an ability to pursue a future collectively and individually as a condition of possibility and not as a form of resistance to the condition of social death.

Seven. Against the script of erasure, various forms of attempts at captivity, the abject rises up, insists upon living. Hartman. Puta Life. Eight. Quote, “recover the insurgent.” state punishment and juridical violence, doling out shame as technique of biopolitical control.

Nine, October 7. Do you condemn Hamas? 10, Rafeef Ziadah. We teach life, sir. But still, he asked me and Ms. Zaidah, don’t you think that everything would be resolved if you would just stop teaching so much hatred to your children? Pause. I look inside of me for strength to be patient. But patience is not at the tip of my tongue as the bombs drop over Gaza.

Today, my body was a TV massacre made to fit into soundbites and word limits and move those that are desensitized to terrorist blood. And between that war crime and massacre, I vent out words and smile. Not exotic, not terrorist.

And I recount. I recount 100 dead, 200 dead, 1,000 dead. We teach life, sir. We Palestinians teach life after they have occupied the last sky. We teach life after they have built their settlements and apartheid walls after the last skies. We teach life, sir. We Palestinians wake up every morning to teach the rest of the world life, sir.

11, Puta Life. The negligible value of the Puta’s life at most negligible. At worst, hunted, denied the value of life. The violence committed against them is to be expected, if not deserved.

12, Puta Life. Connection to sex work must be minimized to humanize the subject. 13, Said. The question of Palestine. The plight for Palestinian self-determination enters official discourse in the United States as terrorism. Do you condemn Hamas?

14, Said. The Palestinian struggle is overwhelmingly penalized, defamed, subjected to disproportionate retaliation. 15, Puta Life. My hope is that we will care more about the sex workers’ life enough to reimagine the psychic and material conditions of their lives.

16, Puta Life. Sex workers as feminist insurgents on a magnitude of scales. 17, Said. The Intifada is a blueprint for Palestinian political and social life. Palestinians as feminist insurgents on a magnitude of scales.

18, justice for some. Freedom is a metaphysical aspiration transcended, embodied corporal sensate and beyond. 19, Puta Life. In their ongoing demands for love, respect, and care, these women of [NON-ENGLISH] remind us of all the ways we are entangled in the radiance of the universe, united in our stubborn insistence to live on.

20, Puta Life. The felt sense as infinitely unfolding possibility that inspires greater and deeper relations of care. 21, by taking up the name, they refuse the stigma. Puta is [NON-ENGLISH]

[APPLAUSE]

[ALBERTO LEDESMA] Thank you so much. So this has been an amazing, very powerful, rich, and evocative conversation. And the book certainly deserves this kind of attention. But that means that we’re a little behind time.

And so I wanted to invite you, Professor Rodríguez, just to give a brief response to what you’ve heard. And maybe we do have about 10 minutes, maybe leave some time for at least one question.

[JUANA MARIA RODRIGUEZ] I’m really happy to– I’ve spoken enough, happy to open it to the floor.

[LEDESMA] Here we have a question here.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Were you able to– oh, thank you. Were you able to look at this movement to honor or at least honor the pain experienced by comfort women and other women in its– I think there’s six court cases right now all over the world of about statues that are controversial.

And I was wondering, did you have a chance to talk to the comfort women– I mean, excuse me, the women of your book about spiritual practices, whether it’s honoring– I think it’s [NON-ENGLISH]? Were you able to get into that at all?

[JUANA MARIA RODRIGUEZ] What I think is curious is people always assume that I did interviews, that I did oral histories, that this is generally what we do. And so much of the scholarship on sex workers is either about law or policy or that

My focus was on representation. I was looking at what was already documented. But I think it’s interesting that, that move to ask the question was precisely the move that I was not wanting to make. There are sex workers all over the world. I understand what’s happening with the comfort women and career right now. There’s just everywhere.

And everywhere I speak, people will freak, oh, this archive, because there are also archives everywhere, including here in the Bay area, such a rich sex worker history. So in terms of the question, I think it was less about asking women some kind of verifiable truth and looking at forms of representation. But I appreciate the question. Yes.

Maybe one quick more question before we wrap up. Does anybody have another question? I did have one question. I think I began asking you– oh, great. We’ll end with that question.

I really loved in here the very opening of your remarks that you framed it as like Puta had already been assigned to you, but it was up to you to decide your relationship to it. And I was wondering, at what point you knew that you would one day write about Vanessa specifically or about– yeah, the way that Puta shaped the ways that you navigate your life too?

[JUANA MARIA RODRIGUEZ] That’s a really good question. And it also speaks to the Academy. So in my dissertation, which became my first book, Sexual Queer Latinidad, I was writing about identity in cyberspace. And the name of the chapter was called Welcome to the Global Stage– Confessions of a Cyber slut, I think was the subtitle.

So in my dissertation, I sort of outed myself, claimed this term. And I don’t think I quite realized what perhaps the implications for that. I did get a job. I still have a job. So I guess that– yeah, so that was sort of putting it into the academic sphere.

One of the reasons why I care so much about this is I work on a college campus where so many people are supplementing their incomes by doing work that sometimes is illegal. Other things like OnlyFans, not illegal, but totally stigmatized.

There are stories– one story of a doctoral student who her dissertation advisor refused to write her letters of recommendation after she came out as having worked as a sex worker. So the fact that sex workers are stigmatized, that there’s an afterlife for that, questions of technology, certainly be important to that.

But that stigma has very real material consequences. And so, yes, I have written about that. And in some ways, I don’t know what jobs or grants I haven’t gotten because of that. But for other people, those consequences are incredibly real and profound.

Thank you.

[ALBERTO LEDESMA] So thank you all for joining us today for this insightful discussion of an amazing book by Professor Juana María Rodríguez. It’s been a privilege to witness the rich exchange of ideas among all of our panelists– Dr. Rojas, Dr. Morris, as well as engaging in some dialogue.

Throughout our conversation, we explored the complex intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, and how visual representation shapes our understanding of Latino experiences, particularly in the context of sex work.

We touched on the importance of challenging dominant narratives and the potential for more ethical forms of relation and care. Themes that resonate deeply in both Professor Rodríguez’s work, and our broader discussions in the fields of ethnic studies and gender studies.

I want to thank or offer my heartfelt thanks particularly to the Social Science Matrix, to Marian, to Chuck for helping us with the technology. And let’s not forget Julia Sizek, who had organized this panel, and we couldn’t do it last term, for all they did.

I also want to thank all of you for attending today and for being here and hearing this powerful presentation. Your engagement and thoughtful questions have certainly enriched this dialogue. Thank you again for coming. And we look forward to seeing you at future events.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[WOMAN’S VOICE] Thank you for listening. To learn more about Social Science Matrix, please visit matrix.berkeley.edu.